Introduction

1. Consumption Officially Enters the Sustainability Debate

As world leaders prepared to gather in Rio de Janeiro in 1992 on the eve of the United Nations (UN) Conference on Environment and Development (also known as the “Earth Summit”), the complexities of unsustainable development were just beginning to dawn on them in uncomfort-able ways. Until then, in the “Global North”, the widely held view was that population growth and poverty were the main unaddressed drivers of environmental harm. Following this framing, nego-tiations at the Summit would need to focus on the “Global South”, given its high rates of fertility and poverty.

But scientific research was beginning to tell a richer, unacknowledged story: in the Global South, negative impacts of activities such as cutting down forests, digging out minerals, and grow-ing bananas and coffee in unsustainable ways, arose primarily from activities undertaken to satisfy the ever-growing appetites of a minority global population in the Global North. In a globalized economy, overproduction in the Global South was the flip side of overconsumption in the Global North.

This reframing of the problem would threaten to derail negotiations at the Summit – it would position countries from the Global North versus those from the Global South, Big Agriculture ver-sus small farmers, foreign aid versus fair compensation for labor and resources, and accusations of neo-colonialism versus corrupt local governance. It would also be a major shift in how environ-mental protection would be perceived by industrial countries; since the 1960s, these countries had invested primarily in controlling pollution generated within their own borders.

In the end, the wording of the final resolution was a balancing act. It stated: “inappropriate development resulting in overconsumption, coupled with an expanding world population” are the cause of environmental degradation (UN, 1992, para 6.1). An entire chapter of the action document was dedicated to “changing consumption patterns”: calling on relevant parties to “develop a better understanding of the role of consumption” and to develop “policies and strategies to encourage changes in unsustainable consumption patterns”. The resulting Report of the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (UN, 1992, para 4.5), better known as Agenda 21, declares:

Although consumption patterns are very high in certain parts of the world, the basic consumer needs of a large section of humanity are not being met. This results in excessive demands and unsustainable lifestyles among the richer segments, which place immense stress on the envi-ronment. The poorer segments, meanwhile, are unable to meet food, health care, shelter and educational needs. Changing consumption patterns will require a multipronged strategy focus-ing on demand, meeting the basic needs of the poor, and reducing wastage and the use of finite resources in the production process

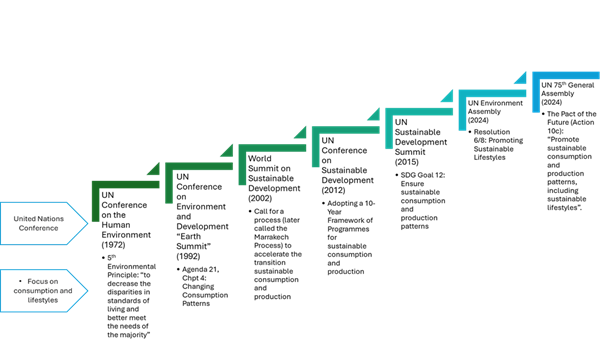

This quote provides an understanding that would shape research, policy and actions on sustainable consumption and lifestyles to this day. Versions of the declaration have percolated through every UN sustainability summit since Agenda 21 (see Figure 0.1), albeit in watered-down interpretations, including the current framework for the sustainable development goals (SDGs).

Global efforts to address unsustainable development from this consumption-population per-spective – by world leaders at the UN negotiations, research scientists, businesses, civil society organizations, and activists – resulted in near-constant tensions and little apparent success. This demonstrates the complexity unveiled by the new problem acknowledgment at the Earth Summit. The continuing rise in global temperatures, biodiversity loss, an increasing number of natural dis-asters, and rising ecosocial tensions, all demonstrate the failure to bring these efforts together effec-tively. It further suggests the urgent need to revisit what and why we consume, how we produce, distribute, and discard the things we do consume, and how our complex production-consumption system is linked to social and ecological tipping points.

This introductory chapter begins by sketching out the origins of consumer society (Section 2), the history and meaning of the term “sustainable consumption” in the global sustainability dis-course (Section 3), and the evolution of the understanding of how the modern societal system of consumption functions (Section 4). Section 5 discusses some of the major challenges standing in the way of a transition to a different organizing principle of societal life, and Section 6 makes the case for creating a vocabulary in which these issues can be widely discussed. The 87 entries in this book represent a non-exhaustive list of established and emerging concepts at the core of language being used in these discussions. Like all languages, this one will evolve over time through use; hopefully, it will result in mobilizing powerful actors to set priorities and affect social change.

2. Engineering a Consumer Society: From the United States to the World

More than half a century before the 1992 Earth Summit, the British economist John Maynard Keynes published his well-known essay Economic Possibilities for our Grandchildren. After observing in his lifetime the huge increase in workers’ productivity in the manufacturing and energy sectors – owing to technological and process innovations, and the harnessing of fossil energy – Keynes predicted that a hundred years from then people will be able to drastically reduce their working hours to about 15 hours per week in order to satisfy their needs. The “economic prob-lem” would be solved. A new challenge would be “for the ordinary person, with no special talents, to occupy himself, especially if he no longer has roots in the soil or in custom or in the beloved conventions of a traditional society”.

Keynes’ predictions have not come to pass. In Europe and North America, working hours have indeed decreased since then, though not nearly in step with continuing productivity growth, as Keynes anticipated. Where he was most mistaken, perhaps, was the assumption that the motivation for people to work is mostly to satisfy their basic needs. He did not consider that, once the “eco-nomic problem” of basic subsistence was solved, cultivated and seemingly insatiable wants would take their place as the motivator for work and the pursuit of well-being.

In Keynes’ days, it was impossible to foresee that a complex societal system would be devel-oped to perpetuate the human drive to satisfy wants through the acquisition and maintenance of goods and services. Nor could it be envisioned that this behavior would become the organizing principle of societal life, including culture, institutions, politics, and the economy. Today, we call this complex system the consumer society.

In her magisterial work A Consumer Republic (2003), historian Lisabeth Cohen describes how, during the three decades after the end of World War II (WWII), consumer society was constructed in the United States. It is instructive to retell this story because the US model soon became a prototype to be exported and replicated throughout the world, overriding alternative models of development (see Box 0.1).

Box 0.1 Construction of consumer society in the United States

After the deprivations of the Great Depression and the sacrifices of WWII, the United States in 1945 was ready for a victorious shopping spree. The government – fearful that the return of war veterans would lead to widespread unemployment – looked to industry to shift its wartime production capacity toward the civilian sector. The Employment Act of 1946 stated that “federal government’s responsibility … [is to] … promote maximum employment, production, and purchasing power”. Industry happily complied by deploying aggressive and sophisticated modern marketing and advertising methods to increase demand for their products. The labor unions too were willing partners in the effort. As early as 1944, the American Federation of Labor (AFL) wrote, “Without adequate purchasing power in the form of wages we cannot get full employment”.

The 1944 “GI Bill” helped returning World War II veterans to get free college education, as well as down payments and government-guaranteed loans for purchasing homes and other goods (Black Americans were excluded). The mortgage interest deductions, government-financed infrastructure, and local zoning laws facilitated the growth of sprawling suburbs, with their endless procession of appliances and furnishings, and high dependence on car-based mobility. The private suburban shopping mall became a public space – stratified by race and income – replacing the previously more egalitarian public spaces of city streets, cafes, and places of commerce. The proliferation of credit cards allowed people to buy now and pay later. The earlier creation of Social Security in 1935 facilitated the transition to mass consumption by relieving Americans from the need to save for old age.

The results were astonishing. National output of goods and services doubled between 1946 and 1956 and doubled again by 1970, driven by private consumption expenditures. From then on, economic growth became a measure of general prosperity driven by consumption. By 1960, 62% of Americans owned their homes, compared to 44% in 1940.

At the peak of the Cold War, American lifestyles also served as an important symbol of the superiority of the capitalist system over Soviet-style socialism. In the famous “kitchen” debate between Vice President Nixon and Soviet Premier Khrushchev at the American Exhibition in Moscow in 1959, Nixon boasted: “The United States [has] come closest to the ideal of prosperity for all in a classless society”.

In short, a major cultural and economic transition took place in the United States in the span of a single generation. The transition not only changed the lifestyles of most Americans in profound ways but also fostered a cultural shift: mass consumption and the suburban lifestyle became almost a national civic religion, conflated with such fundamental human aspirations as well-being and democracy.

Source: Adapted from Cohen (2003)

By the 1970s, 20 years before at the Earth Summit consumerism was recognized as a global ecological problem, all key pillars of the growth-oriented consumer society were firmly in place: the debt-financed economy – both household and government – that demanded growth to survive; pension funds dependent on growth to deliver on their commitments; the financial system happy to fuel growth, both real and imagined; and the ever-rising aspirations of households. By the 1970s, consumers as a distinct class, transcending the traditional sociological groupings by age, race, wealth, education, or political leanings, became a political force to reckon with. Through boycotts, buycotts, and other public campaigns, consumer movements punished and rewarded companies for their social and ecological impacts. Consumer protection laws were adopted to protect that distinct class.

The neoliberal ideology – which proclaimed that greed and wealth accumulation are good, markets know best, and government is a drag on the economy – came to the fore in the late 1970s and extended its influence to the present day. Its policies emphasize free trade, deregulation, lower taxes, increasing consumption to grow the economy, and promoting the ideology of consumer sov-ereignty. It intentionally conflates a consumer with a citizen and creates a transactional relationship between citizens and the government: the purpose of public policy would increasingly not be to serve the public good but rather to satisfy the consumer-voter.

In the next logical stage of maturation, by the mid- to late 20th century, many elements of neo-liberalism and the US-style consumer society spread to other parts of the world, first in the indus-trial economies of North America and Western Europe, then in Asia and post-socialist Europe, and finally in capitals and major cities of the rest of the world.

3. Defining Sustainable Consumption, Sustainable Lifestyles – and Sustainable Living

Despite its growing use in research and policy circles, the operational meaning of the term sus-tainable consumption is quite fluid. Some may associate it with daily household decisions such as minimal shopping, leisure flying, and taking cruises, and with green and ethical shopping. For social activists, sustainable consumption may bring to mind changing personal and community value systems, norms, social practices, personal priorities, diet, or adopting a minimalist way of life. From a policy perspective, sustainable consumption may signify a personal carbon budget, shorter workweek, limits on advertising, and more efficient buildings and mobility infrastructure; while the political economy perspective points toward a diminished role of the financial sector, degrowth, a steady-state economy, taxation reform, and reigning in corporate power. Each per-spective has its own language and shared understandings among its adherents, but communication between them is inadequate.

Most definitions of sustainable consumption and lifestyles are modifications of the now-classic definition of sustainable development offered by the World Commission on Environment and Development (known as the Brundtland Report, titled Our Common Future): “sustainable devel-opment is development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs” (WCED, 1987). Although the root concepts “lifestyle” and “consumption” have been previously defined by academics, the modifier “sustainable” brings additional complexity to the definitions.

Sustainable consumption is both a concept and a practice, and research on it sets out to under-stand and promote the types of consumption behaviors that are conducive to a sustainable soci-ety. This is reflected in one of its earliest and most widely used definitions (known as the “Oslo Declaration”):

Sustainable consumption is “the use of goods and services that respond to basic needs and bring a better quality of life, while minimizing the use of natural resources, toxic materials and emissions of waste and pollutants over the life cycle, so as not to jeopardize the needs of future generations”. (Ofstad et al., 1994)

The concept of sustainable lifestyles goes beyond consumption, however. It speaks to more com-plex and intangible aspects of human life, including habits, social practices, traditions, aspirations, and the search for meaning, all embedded in societal structures: physical, economic, cultural, and political. A 2016 definition captures this complexity:

A sustainable lifestyle minimizes ecological impacts while enabling a flourishing life for indi-viduals, households, communities, and beyond. (Vergragt et al., 2016)

In policy and academic discourse, the two terms – sustainable consumption and sustainable lifestyles – are often used interchangeably, and confusingly so (Gabriel & Lang, 2006; Miles, 1998). One helps to define the other and vice versa: sustainable consumption research empha-sizes the material aspect of sustainable lifestyles, and conversely, lifestyles determine one’s consumption patterns. While sustainable consumption tends to address decisions and actions linked to the purchase, use, and disposal of material products and services, the term sustain-able lifestyle incorporates other actions in the context of values, education, community, and infrastructure.

One term that easily connects sustainable consumption and sustainable lifestyles is “sustainable living”. While encompassing both terms, it does so without taking on the notion of “lifestyle” as advertised by corporate marketing.

Sustainable living is equitable consumption and lifestyles that contribute to wellbeing of indi-viduals and society within ecological limits. (Akenji, 2019)

This definition has at its core three key elements: ecological limits as a basis and boundary for pro-viding individual and societal needs; equity and justice in how we organize ourselves as a society and pursue our needs; and well-being as a shared objective. It also recognizes that consumption and lifestyles are embedded in a societal context, including institutions, norms, and infrastructures that frame and shape individual and collective choices. Implicit in the definition is the recognition that there is more than one way of living sustainably; there are different approaches by different individuals and societies that could be described as sustainable.

The concept of sustainable living also accommodates a broader set of relevant concepts, such as voluntary simplicity, minimalism, sufficiency, and healthy living – often combining physical, emotional, and spiritual health with a more limited role for materialism. In public health parlance, sustainable living promotes health and well-being for individuals, communities, and the planet by balancing ecological, economic, and social systems; in business, it would be reflected in work-life balance and employment conditions; and in marketing, promotion of “green” or healthy products and services.

Because of their overlaps and variations, the above three terms and definitions are used across different entries in this book. The emergence of these concepts can be seen in the evolving under-standing of consumer society elaborated in the following section.

4. Evolving Understanding of Consumer Society as a Complex System

Over the millennia, scholars, religious leaders, and social commentators have expressed criticism of unrestrained wealth accumulation, consumption, and their underpinnings – greed, gluttony, acquisitiveness, profit-seeking, excessive luxury, and positional consumption. In the 20th century, writers such as Veblen (The Theory of the Leisure Class, 1899), Galbraith (The Affluent Society, 1958), Marcuse (One-Dimensional Man, 1964), Elgin (Voluntary Simplicity, 1981), and others focused largely on the moral, class, and existential dimensions of mass consumption and its impact on the quality of modern life.

That changed in 1992 when at the Earth Summit, consumerism was officially declared a global ecological problem. Since then, sustainable consumption and consumerism have attracted increas-ing attention from scientists, community activists, and policymakers. Much of the early research on the topic of consumption focused on consumer behavior. After all, the consumer is the most visible end-user of market products and is often assumed to have free will and rational expres-sion of choice. Economic, social, and psychological theories have been used to explain the role of consumers as economic actors and to theorize about their motivations and drivers (Ajzen, 1991; Bourdieu, 1984; Thaler, 1980, 2016).

But people do not go about as rational, fully informed, and fully autonomous actors in the for-mal economy, as often attributed to them in economic theories. And while their pursuit of meaning and well-being must include the acquisition of goods and services, people do not solely seek these things through material means. “People also love, generate ideas, express their value systems, take care of family, create art, cherish silence, pray, fast, in ways that material flows and market economics cannot account for” (Akenji, 2019). They are also influenced by traditions and social norms, constrained by physical and regulatory infrastructure, and manipulated by sophisticated advertising. Part of the challenge of research for sustainable consumption and lifestyles is that these mixtures of material and psychological, rational and emotional, biological and cultural, all come together in vastly differing configurations across billions of people. Steven Miles (1998) has noted that “How we consume, why we consume, and the param-eters laid down for us within which we consume have become increasingly significant influ-ences on how we construct our everyday lives”. The statement recognizes that lifestyles occur within, or are railroaded by, broader social and physical contexts; in approaching sustainable living, it is important to differentiate between factors at the individual or the household level, and those that are beyond (direct) individual control (Wallnoefer et al., 2024). Scholars thus began to argue that focusing on the individual consumer is problematic because it fails to recognize the historical, political, and social conditions that shape everyday life, including our consumption patterns. The frame thus expanded from consuming individuals to a system of consumption. Books such as Schor’s The Overworked American (1993) and The Overspent American (1998), De Graaf’s Affluenza (2001), Maniates’s and Princen’s Confronting Consumption (2002), and works of several other authors featured in Jackson’s Earthscan Reader on Sustainable Consump-tion (2006) recognized that consumption is a manifestation of both basic human psychology and intentionally designed societal systems, including the ways employment and economy are organ-ized. Their work was further extended by Shove et al. (2012) who used social practice theory to emphasize that consumption is a collective act transmitted through widely accepted social norms and practices.

The psychological perspective on consumption – widely used until then and accused by many of “blaming the victim” or consumer scapegoatism – gave way to institutional theories, cultural analyses, macroeconomics, and theories of social change and collective action.

Scholars have emphasized the deliberate construction of the system of consumption in the United States and linked it specifically to the economic growth paradigm and, importantly, to its ideological underpinnings created during the Cold War period (see Section 2). While the idea of a deliberate construction implies that, at least in principle, the system of consumption could be dis-mantled, the ideological dimension also highlights the difficulty of doing so. This was illustrated by US President Bush’s famous declaration in 1992 that “the American way of life is not up for negotiation. Period”.

Research on consumption also began to increasingly draw on more quantitative method-ologies like natural resource accounting. Using methods such as Environmentally-Extended Multi-Regional Input-Output analysis enabled researchers to estimate the material and carbon “footprint” of a given consumption pattern and to show a clear correlation between the level of income, resource consumption, and environmental impacts. This focus on materials and energy, economic behaviors, and the desire for modeling and quantification partly explains why process and product optimization and technological innovations have become prevalent policy recommen-dations for climate mitigation (Akenji, 2019). The landmark report by Jackson (2009) Prosperity Without Growth delved deeper into the sys-temic nature of mass consumption. It specifically highlighted the links between mass consump-tion and economic growth, the associated role of the financial sector, and the impact of economic globalization, which made mass production cheaper and the useful life of products shorter. The report challenged the notion that absolute decoupling of economic growth from the use of energy is achievable through technological solutions. Jackson followed in the footsteps of Herman Daly’s (1993) theory of the steady-state economy and Peter Victor’s (2008) macroeconomic models of such an economy in Canada.

From then on, questioning the powerful dominance of technological solutions to ecological cri-sis (also referred to as “techno-optimism”, “weak sustainability approach”, and “green technology approach”) and of absolute decoupling of economic growth from energy and material use – once the position of a tiny minority – would gain more currency among academics (Alfredsson et al., 2018; Parrique et al., 2019). We clearly need both green technology and demand reduction through life-style changes (see Box 0.2). Nonetheless, in the very real world of politics and policymaking, the dominance of technology-based over lifestyle-based approaches to climate mitigation continues.

Box 0.2 Limitations of the green technology approach

There are a number of key limitations to an approach that pins its hopes on green technology and efficiency improvements. These include the following:

- Efficiency is blind to the upper limits of emissions, and so we can keep improving it even as we transgress the planetary boundaries.

- Owing to the rebound effect, the sheer increase in the scale of consumption during the past several decades has canceled out the efficiency gains. No country in the world has succeeded in “absolute decoupling” of economic growth from environmental impacts. Not even (or, especially not) the Scandinavian countries that appear at the top of most indexes of progress – but with per capita footprints that would need multiple Earths.

- The technology-based approach focuses on the symptoms, not the causes of the unsustainability. At the fundamental level, we need to address overproduction in relation to overconsumption.

- The promises of the technology-based approach have failed to deliver over the last several decades (see carbon-sucking machines, geoengineering, and electric vehicles, for example). There is yet no plausible scenario for replacing our entire car stock or providing every family in the world with an efficient electric vehicle without great ecological damage.

- The technology-based approach widens the wealth gap because it is the rich who tend to own the patents or invest in these technologies.

- According to the International Energy Agency, global growth of energy demand in 2024 and 2025 is expected to be 4% annually relative to the preceding year. At this rate of increase, the supply of renewable energy does not keep up with the growth of demand, despite its own exponential growth rate (IEA, 2024). This means that fossil-fuel-generated electricity makes up the difference.

- Increasing renewable energy generation brings about other ecological problems owing to the increased demand for minerals and rare earth metals as well as political instability in mining regions (see Energy Overshoot).

Source: Adapted from “The (Technology) Efficiency Paradox”, blog post by Lewis Akenji, available at www.hotorcool.org

The understanding of the attraction of consumer society and a potential transition beyond it has been greatly enriched by so-called happiness and subjective well-being research (Smith & Reid, 2018). Numerous scholars, among them Layard (2006), Kahneman and Deaton (2010), Tsurumi et al. (2021), Graham (2011), and Skidelsky and Skidelsky (2012), to name a few, interrogated such questions as: Does wealth accumulation and consumption make people happy? Is there a saturation point? How much is enough?

The answers are not straightforward. On the one hand, deprivation is a source of unhappiness in life; and friends, family, and a sense of belonging are the true long-lasting sources of life satisfac-tion. Research findings also suggested a point of saturation; beyond a moderate per capita income, additional income does not lead to greater happiness or satisfaction with life. On the other hand, satisfaction with material life is a relative concept. It is deeply grounded in social comparisons and how much one has relative to others (Kahneman & Deaton, 2010; Killingsworth et al., 2023). That leads to a kind of arms race: while the top earners strive to distance themselves from the rest (including their peers) by accumulating and spending more, those in the lower economic classes strive to emulate them and distance themselves from those below them. The phenomenon applies to all economic strata and brings a lot of stress to people’s lives and little happiness to most. At the time of this writing, complexities in the system of mass consumption – its components and mutual interdependencies in the context of a global economy – are generally recognized, but points of intervention are less clear. While the case for transitioning toward a different organiz-ing principle of societal life is strong, conversations about the point of departure and destination lack common ground. There are other major challenges to contend with. Three among those – the socio-economic impact of reducing consumption, the inequality between the Global North and Global South, and wealth inequality within countries – especially stand out.

5. Challenges to System Transition

Economic and Political Implications of Diminished Consumption

In recent years, various branches of the United Nations, as well as European governments and the EU, have adopted official proclamations about the need to reduce consumption.

For example, the European Commission’s New Energy Efficiency Directive (EU/2023/1791) established a weak, politically tainted but legally binding target to reduce the EU’s final energy con-sumption by 11.7% by 2030, based on 2020 scenarios. In the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) framework, Goal 12 is on Responsible Consumption, Goal 10 is on Reducing Inequalities, and Goal 3 is on Wellbeing. The adoption of the UN 10-Year Framework of Programmes for Sustainable Consumption and Production (10YFP) in 2012 at the Rio+20 Summit so far stands out as the most ambitious approach to the issue by the UN system, but the mandate is poorly under-resourced and has no functional implementation mechanism. In 2024, the UN Environment Assembly adopted a resolution (6/8) titled “Promoting Sustainable Lifestyles”. The same year, at the UN’s 75th General Assembly, the 193-member organization adopted “The Pact for the Future”, in which it commits (Action 10c) to “Promote sustainable consumption and production patterns, including sustainable lifestyles”.

Even the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), which since its inception in 1988 has primarily focused on technical assessments and mitigation, devoted an entire chapter of its Sixth Report (2022) to sustainable consumption and sufficiency. It estimates that changes in systems of consumption and lifestyles by 2050 can potentially reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 40 to 70% (IPCC, 2023). A study published in Nature went beyond carbon emissions, finding that reducing con-sumption among just the top 10% or 20% of the world’s consumers would go a long way to reducing overshoot of most planetary boundaries, decreasing environmental pressure by 25 to 53% (Tian et al., 2024). The media are also writing about consumption with growing frequency. The detailed and accessible analysis in the 1.5-degree lifestyles reports by Hot or Cool Institute (Akenji et al., 2021) has been repeatedly featured in mainstream media such as the BBC, Financial Times, The New York Times, Bloomberg News, Forbes, and multiple international and local mainstream media outlets.

Governments are nonetheless averse to abandoning the economic growth paradigm. And for good reason. What remains unresolved is the potential socio-economic impact of rapid reductions in consumption: recession, unemployment, and massive economic dislocations, both among the consumers in the Global North and among producers in the Global South. Some scholars have attempted to develop scenarios and macroeconomic models for such a transition (Victor, 2008), but many questions remain open. For instance, all private and public pension plans depend on future growth to deliver on their commitments; in the United States, meanwhile, much of the public ser-vice sector, such as public radio and television, depends on advertising revenues for their operat-ing budgets. These examples are just the tip of the iceberg.

After decades of following the neoliberal economic model, national governments are also deeply constrained by the enormous power of multinational corporations, which demand growth and mass consumption (Slobodian, 2018). Governments thus cling to the idea that economic growth can continue as long as it is decoupled from resources. Green consumerism and green growth are the operative words. This framing has allowed governments to pay lip service to sustainable consump-tion while still tacitly or explicitly encouraging mass consumption. They look to technological and market solutions for what is essentially a social and political problem.

Inequality

As noted earlier, inequality within countries drives consumption because people strive to raise their social status by emulating those “above them”. The groundbreaking 2009 and 2019 studies by British epidemiologists Wilkinson and Pickett illuminate other corrosive effects of inequality by showing that it is a powerful social stressor that is increasingly rendering societies dysfunc-tional. For example, bigger gaps between the rich and the poor are accompanied by higher rates of homicide and imprisonment, more infant mortality, obesity, drug abuse, and COVID-19 deaths, as well as higher rates of teenage pregnancy and lower levels of child well-being and social mobility. These findings imply an alternative to economic growth as a way to solve many social ills: reducing inequality. But approaching sustainability from this inequality perspective conjures the specter of wealth redistribution: a political third rail. This is another great challenge of our times.

Inequality within societies has another corrosive effect on the politics of system transition. Reaching broad societal support for action on that scale requires social cohesion and a feeling that everybody contributes their share. But in highly unequal societies, social trust, cohesion, and solidarity are greatly eroded. It is hard to build support for collective action if people feel that the burden is not being shared fairly (Wilkinson & Pickett, 2024).

Inequality between countries is another unresolved issue. The tension between the rich and poor countries of the Global North and Global South was already evident at the 1992 Earth Summit and continues to clog up global negotiations on who should pay for loss and damage due to impacts of climate change, and the costs of climate mitigation and adaptation. Although climate change is a consequence of environmental destruction, overconsumption, and historical emissions by the rich countries of the Global North, countries of the Global South are facing its worst impacts.

On top of that, poorer countries are trapped in a neo-colonial and extractive global economic system that is forcing them to use their limited financial and natural resources to continue to sup-ply the rich countries of the Global North, instead of developing their own economies or building their own resilience. Analysis by the International Resources Panel (IRP, 2024) shows that, through global trade, rich countries displace environmental impacts onto others, and that rich countries use six times more materials per capita and are responsible for ten times more climate impacts per capita than low-income countries.

In addition to the issue of historical responsibility, the shrinking size of the global carbon budget and the power disparities in international negotiations make changes in energy consumption a zero-sum game: an increase in the Global South requires a decrease in the Global North. In 2017, Hubacek et al. estimated that bringing the 837 million people living in extreme poverty to the level of consumption that is referred to as poor would have a minimal impact on the global car-bon budget; but bringing the poor of the world (half of its population) to a more dignified state of existence might raise the global temperature by 0.6 degrees by the end of the century. More recent estimates put the impact of eradicating poverty somewhat lower, but not negligible (Oswald et al., 2021; Baltruszewicz et al., 2021, 2023).

Even as climate change forces the need to reduce emissions and as resource stocks dwindle, the International Resources Panel warns that

without urgent and concerted action to change the way resources are used, material resource extraction could increase by almost 60 per cent from 2020 levels by 2060. . . far exceeding what is required to meet essential human needs for all in line with the SDGs.

Without addressing these tensions between resource needs and availability, and the asymmetries in political and economic power, countries of the Global South are unlikely to meet their material needs, and the Global North would pull the rest of the world into a deeper climate overshoot.

Envisioning Sustainable Consumption and Lifestyles

Aiming for global carbon equality would mean a radical change in lifestyles in the Global North. What would such a low-impact life look like? In this volume, we include some metaphors that attempt to define it by adopting the idea of minima and maxima: earth systems boundaries (Röck-ström et al., 2023), doughnut economics, consumption corridors, and fair consumption space. These differ in respective emphases on physical and social factors, equity, justice, and the degree of quantification, but all aim to define boundaries: the lower boundary ensures dignified, equitable living below which no one should fall; and the upper one defines the biophysical limits that should not be exceeded.

We also include examples of visions – some descriptive, others using quantitative models – of an economy capable of delivering such a life within boundaries: steady-state economy, sharing economy, circular economy, and society and foundational economy. Some papers highlight principles and policies that could form the basis of a society with sustainable lifestyles: sufficiency (Princen, 2003), for instance, or changing provisioning systems by adopting universal basic ser-vices for fundamental needs (Gough, 2019).

Using theoretical models, some researchers have sharpened the picture of a life within bounda-ries and under the scenario of equality by producing specific numbers to describe it. In modeling so-called 1.5-degree lifestyles, they consider factors such as the size of living space, access to basic amenities, sufficient nutrition, basic mobility, and others (Akenji et al., 2021; Oswald et al., 2021; Baltruszewicz et al., 2021, 2023). The results all demonstrate a large gap between the current average lifestyles of citizens in affluent societies and lifestyles of sufficiency.

The irony of envisioning and calling for sufficiency lifestyles in wealthy societies is that low-income people in these countries already provide elements of a living model of it (see, for instance, examples from Norway, reported by Korsnes et al., 2024; see also Pungas et al., 2024). By necessity, they develop procedures and understandings that support lower consumption levels, like sharing, volunteering, repairing, negotiating needs, and calculating costs. Many more exam-ples of sustainable lifestyles, especially in the Global South, can be found in a compendium similar to this one, called Pluriverse: A post-development dictionary (Kothari et al., 2019).

Notably, the frugality, simplicity, and sharing that are practiced by low-income people are often the same ones that the abundant literature on sustainable lifestyles presents as a model for achiev-ing more life satisfaction through community participation and more leisure time. But this kind of life also often comes with stigmas, a sense of social exclusion, and low social standing – hardly a situation to emulate. This in turn undermines social cohesion and solidarity, which are necessary for social change.

Thus the challenge for policymakers and advocates is to create the conditions under which low consumption lifestyles are the norm, fair to everyone, and easiest to practice. Efficiency-oriented policies, such as subsidies for heat pumps and electric cars, which work best for economically strong groups, are not up to the task and still have their own environmental impacts. Social activ-ism to bring about value shifts plays a relevant role in sustainability transitions for mainstreaming sustainable lifestyles out of their current niche. Several concepts explored in this book are relevant for considering how to create such conditions, among them choice editing, carbon budgets, grass-roots innovation, buen vivir and buenos convivires, ubuntu, living labs, eco-communities, and community-supported agriculture.

6. The Need for a Common Language

A major barrier to making sustainable consumption and lifestyles a high-profile issue is that it does not have a political champion; it is a political orphan. At the time of this writing, the websites of leading global and national environmental organizations do not mention unsustainable consump-tion or unrestrained economic growth, although inequality is highlighted. This should not come as a surprise. The research roots of the modern environmental movement are in natural sciences and technology; technological and supply-side solutions to ecological overshoot are therefore their natural choices. Furthermore, it is much easier to mobilize their constituency by targeting the business world as villains and human health as under threat – as was the case with environ-mental pollution from the 1960s on – than by challenging dominant lifestyles (see Box 0.3). Neither is there much explicit discussion of sustainable lifestyles among advocates for social justice or public health.

Box 0.3 Environmental movement coalition in the twentieth century

In the United States and Europe, great reforms were introduced in controlling air, water, and soil pollution during the early 20th century, largely owing to the political advocacy of the public health community and, by the 1960s, also environmental organizations. The community of epidemiologists, medical professionals, and environmental scientists that emerged shared a professional language and worldviews. They performed an essential role in generating scientific data about the adverse effects of pollution and chemical contamination on health, disseminated that body of knowledge in scientific publications and mainstream media, and vigorously advocated for government policies.

In the 1960s, they were instrumental in building a broad-based coalition of scientists, environmental activists, and the alarmed public in affecting social change: building regulatory institutions, enacting laws, and allocating public funds (Brown et al., 1997). This same type of coalition was responsible for banning indoor tobacco smoking in the 1990s and early 2000s.

The problem of overconsumption is of course more complex than that of toxic pollution. And consumers who are concerned about their future quality of life are slow to accept the idea of sus-tainable consumption and lifestyles.

Conceptual barriers to collective action accompany the political ones. The transdisciplinary nature of sustainable consumption and lifestyles research hampers the emergence of a coherent community of scholar-advocates who share a language and worldviews. Suggested points of inter-vention are often based on fragmented findings and siloed perspectives rather than a unified per-spective (Wallnoefer, 2022). The result is that people and institutions who should communicate with each other do so poorly or not at all and graduates from sustainability programs who are eager to engage in social activism are often only familiar with a sliver of the big picture but without a good understanding of how all the pieces fit together.

These obstacles do not, however, justify inaction. Indeed, they are a clarion call for action. It is necessary to build a coalition of multidisciplinary academics, activists, policymakers, and business leaders who understand the urgency of shifting to a different organizing principle of societal life, and who can see opportunities in doing so. Creating a broad-based discourse that draws on the many concepts included in this book is the first step.

We are encouraged by the signs of a growing interest in consumption reduction policies among citizens in high-consuming countries. A recent study in ten European countries, for instance, showed that citizens are more committed to sufficiency policies than the authors of the National Energy and Climate Plans (Lage et al., 2023). In France, several recent reports on sufficiency have received considerable public attention (Bourliaguet, 2025). Cities like The Hague are ban-ning fossil fuel-related advertisements, which are a relevant driver of unsustainable consumption. Conversations around degrowth and post-growth approaches have also blossomed, fundamentally questioning what has been called the “imperial mode of living” (Brand & Wissen, 2021). This has brought such debates into prominent conferences in the European Union and national parliaments. There is also a long tradition and a more recent surge of civil experimentation and activism, quite often not under the banner of sustainable consumption, but very relevant for its development. Many of these are in the lower-consuming countries of the Global South (Kothari et al., 2019). Var-ious promising civil society developments are tackled in the book under topics such as subvertis-ing, grassroots innovation, alternative hedonism, green parenting, and community-supported agriculture.

7. Structure of the Book

This book seeks to curate and organize a shared vocabulary for the broad, transdisciplinary com-munities working on a transition toward sustainable consumption and lifestyles, especially in the high-consuming countries. It is also aimed at people who want to better understand those ideas and how they relate to each other. It strives to assess how far the discipline has matured and to highlight some of the emerging concepts that could become relevant for sustainable futures. Together, the entries in this book attempt to reclaim some of the language from appropriation and greenwashing, and to challenge some myths and misconceptions about sustainable consumption and lifestyles. Ultimately, we hope that it provides inspiration for researchers, practitioners, activists, innovators, and observers on how to collectively move toward a more sustainable society. The 87 essays are organized into five clusters with overlapping boundaries (see Box 0.4). Clus-ter I includes entries focusing mainly on actions by individuals, households, and social groups; Cluster II is more theoretical, including abstract concepts, frameworks, and applied theories. Clus-ter III takes a political economy perspective; Cluster IV focuses on social activism and value shifts; and Cluster V addresses governance, policy, and choice architecture.

Each entry provides a definition, a brief history of the concept, and a reflection on the various perspectives on the topic, as well as its applications and implications for a transition to a sustain-able consumption system. To facilitate cross-referencing between entries, we have marked the connections with other entries in bold. The result is a mosaic of concepts, most of them intercon-nected, which together form the “Vocabulary” that can be used to have a dialogue on sustainable living, consumption and lifestyles. This mosaic is important not only for a collective conversation but also for identifying leverage points for systemic change. Without a shared understanding of the issues at stake and of the various concepts that matter, it is hard to imagine purposeful social action.

In the entries, we avoided large bibliographies, as would be the case in a review article. This is because we seek to offer the reader a generally understood and self-contained description of each concept in the context of a transition to a system of sustainable consumption and lifestyles. Read-ers who want to know more about a topic can follow up with further research of their own, starting with the list of five additional readings.

Box 0.4 Clusters of concepts

- Cluster I: Daily Household Decisions and Lifestyles takes the perspective of the consumer. How and when do consumers make decisions on where to live, how they get from point A to B, how they spend their free time, and what they eat and drink? It also explores examples of sustainable lifestyles, emerging ways of living, and how communities are experimenting, as well as some barriers to change.

- Cluster II: Concepts, Frameworks, and Applied Theories brings us to the conceptual underpinnings of sustainable and unsustainable consumption. It explores how lifestyles and consumption patterns are determined by behavioral and structural drivers and barriers, points of intervention to trigger change, and potential outcomes of transformation processes.

- Cluster III: Political Economy takes a systemic view of consumer society, including economic structures, the role of finance and money, power relations, and inequality. It reflects on potential types of different economic paradigms, and what principles could be relevant to follow.

- Cluster IV: Social Activism and Value Shifts looks at the myriad of social experiments and actions to enhance well-being with a smaller footprint. This cluster also reflects on the interpretations of collective well-being in different cultures and social contexts, as well as the role of education. It addresses how individuals can take action within and beyond their role as consumers, and what alternative ways of living could serve as orientation for that.

- Cluster V: Governance, Policy, and Choice Architecture focuses on institutional arrangements and government policies to facilitate sustainable consumption and lifestyles. This explores how sustainable lifestyles can be enabled through structural, legislative, cultural, and technological changes that default toward mainstreamed sustainable choice options and behavioral patterns.

8. References

Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T.

Akenji, L. (2019). Avoiding consumer scapegoatism: Towards a political economy of sustainable living. Uni-versity of Helsinki.

Akenji, L., Bengtsson, M., Toivio, V., Lettenmeier, M., Fawcett, T., Parag, T., Saheb, Y., Andersen, R., Hoff, H., Nissinen, K., & Rees, W. (2021). 1.5-degree lifestyles: Towards a fair consumption space for all. Hot or Cool Institute. Available at: https://hotorcool.org/1-5-degree-lifestyles

Alfredsson, E., Bengtsson, M., Brown, H.S., Isenhour, C., Lorek, S., Stevis, D., & Vergragt, P. (2018). Why achieving the Paris Agreement requires reduced overall consumption and production. Sustainability: Sci-ence, Practice and Policy, 14(1), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1080/15487733.2018.1458815.

Auden, S. (2021). Worrying about your carbon footprint is exactly what big oil wants you to do. The New York Times.

Baltruszewicz, M., Steinberger, J.K., Ivanova, D., Brand-Correa, L.I., Paavola, J., & Owen, A. (2021). House-hold final energy footprints in Nepal, Vietnam and Zambia: Composition, inequality and links to well-being. Environmental Research Letters, 16(2), 025011. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/abd588. Baltruszewicz, M., Steinberger, J.K., Paavola, J., Ivanova, D., Brand-Correa, L.I., & Owen, A. (2023). Social outcomes of energy use in the United Kingdom: Household energy footprints and their links to well-being. Ecological Economics, 205. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2022.107686. Bauman, Z., & Miles, S. (1999). Consumerism as a way of life. Social Forces, 78. https://doi. org/10.2307/3005817. Bourdieu, P. (1984). Distinction: A social critique of the judgement of taste. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Uni-versity Press. Bourliaguet, B. (2025). Rethinking the energy transition: Sufficiency and the French strategy. Energy Research & Social Science, 124, 104055. https://doi.org.10.1016/j.erss.2025.104055. Brand, U., & Wissen, M. (2021). The imperial mode of living. New York: Verso. Brown, H.S., Cook, B., Shatkin, J.A., Krueger, J.R. (1997). Reassessing the History of Hazardous Waste Dis-posal Policy in the United States: Problem Definition, Expert Knowledge, and Agenda-Setting. Risk, Issues and Health, Safety and Environment, 249–272. Cohen, L. (2003). A consumers’ republic: The politics of mass consumption in postwar America. 1st Paper-back ed. Vintage Books. Daly, H.E. (1993). Steady-state economics: A new paradigm. New Literary History, 24. https://doi. org/10.2307/469394.

De Graaf, J., Wann, D., & Naylor, T.H. (2001). Affluenza: The all-consuming epidemic. Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

Demand, Services and Social Aspects of Mitigation. (2023). Climate change 2022 – Mitigation of climate change. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009157926.007.

Dubois, G., Sovacool, B., Aall, C., Nilsson, M., Barbier, C., Herrmann, A., Bruyère, S., Andersson, C., Skold, B., Nadaud, F., Dorner, F., Moberg, K.R., Ceron, J.P., Fischer, H., Amelung, D., Baltruszewicz, M., Fis-cher, J., Benevise, F., Louis, V.R., & Sauerborn, R. (2019). It starts at home? Climate policies targeting household consumption and behavioral decisions are key to low-carbon futures. Energy Research & Social Science, 52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2019.02.001. Elgin, D. (1981). Voluntary simplicity: Toward a way of life that is outwardly simple, inwardly rich. New York:

William Morrow. Gabriel, Y., & Lang, T. (2006). Unmanageable consumer. 2nd ed. London: Sage Publications. https://doi. org/10.1017/CBO9781107415324.004. Graham, C. (2011). The pursuit of happiness: An economy of well-being. Brookings Institution. Gough, I. (2019). Universal basic services: A theoretical and moral framework. Political Quarterly, 90(3), 534–542. ISSN: 0032-3179.

Gupta, J., Liverman, D., Prodani, K., Aldunce, P., Bai, X., Broadgate, W., Ciobanu, D., Gifford, L., Gordon, C., Hurlbert, M., Inoue, C.Y.A., Jacobson, L., Kanie, N., Lade, S.J., Lenton, T.M., Obura, D., Okereke, C., Otto, I.M., Pereira, L., Rockström, J., Scholtens, J., Rocha, J., Stewart-Koster, B., David Tàbara, J., Rammelt, C., & Verburg, P.H. (2023). Earth system justice needed to identify and live within Earth system boundaries. Nature Sustainability, 6, 630–638. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-023-01064-1.

Hirao, M., Tasaki, T., Hotta, Y., & Kanie, N. (2021). Policy development for reconfiguring consumption and

production patterns in the Asian region. Global Environmental Research, 25(1&2). IEA. (2024). Global electricity demand set to rise strongly this year and next, reflecting its expanding role in energy systems around the world. International Energy Agency. Available at: https://www.iea.org/news/ global-electricity-demand-set-to-rise-strongly-this-year-and-next-reflecting-its-expanding-role-in-energy-systems-around-the-world IPCC. (2023). IPCC report 2023. In Climate change 2023: Synthesis report. International Panel for Climate Change. Available at: https://www.ipcc.ch/report/sixth-assessment-report-cycle/. IRP. (2024). Global resources outlook 2024: Bend the trend – pathways to a liveable planet as resource use spikes. International Resource Panel. Available at: https://www.resourcepanel.org/reports/global-resources-outlook-2024. Jackson, T. (2006). The earthscan reader on sustainable consumption. Routledge. Jackson, T. (2009). Prosperity without growth: Economics for a finite planet. 1st ed. London: Routledge. https://doi.org/0.4324/9781849774338.

Jackson, T., Victor, P.A., & Naqvi, A. (2016). Towards a Stock-Flow Consistent Ecological Macroeconomics. PASSAGE Prosperity and Sustainability in the Green Economy.

Jungell-Michelsson, J., & Heikkurinen, P. (2022). Sufficiency: A systematic literature review. Ecological Eco-nomics, 195. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2022.107380 Kahneman, D., & Deaton, A. (2010). High income improves evaluation of life but not emotional well-being. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 107(38), 16489–16493. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1011492107

Keynes, J.M. (1930). Economic possibilities for our grandchildren (1930). In Essays in persuasion. New York:

W.W. Norton & Co., 1963. Killingsworth, M.A., Kahneman, D., & Mellers, B. (2023). Income and emotional well-being: A conflict resolved. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 120(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2208661120 Korsnes, M., & Solbu, G. (2024). Can sufficiency become the new normal? Exploring consumption pat-terns of low-income groups in Norway. Consumption and Society. https://doi.org/10.1332/27528499y20 24d000000009. Kothari, A., Salleh, A., Escobar, A., Demaria, F., & Acosta, A. (2019). Pluriverse – a post-development dic-tionary. New Delhi: Tulika Books. Lage, J., Thema, J., Zell-Ziegler, C., Best, B., Cordroch, L., & Wiese, F. (2023). Citizens call for sufficiency and regulation – A comparison of European citizen assemblies and National Energy and Climate Plans. Energy Research & Social Science, 104, 103254. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2023.103254. Layard, R. (2006). Happiness: Lessons from a new science. London: Penguin Group.

Marcuse, H. (1964). One-dimensional man: Studies in the ideology of advanced industrial society. Boston: Beacon Press. Miles, S. (1998). Consumerism: As a way of life. London: Sage Publications.

Millward-Hopkins, J., Steinberger, J.K., Rao, N.D., & Oswald, Y. (2020). Providing decent living with minimum energy: A global scenario. Global Environmental Change, 65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. gloenvcha.2020.102168 Ofstad, S., Westly, L., & Bratelli, T. (1994). Symposium: Sustainable consumption: 19–20 January 1994: Oslo, Norway. Oslo, Norway: Ministry of Environment. Olmsted, M.S., & Galbraith, J.K. (1958). The affluent society. American Sociological Review, 23. https://doi. org/10.2307/2089073 Oswald, Y., Steinberger, J.K., Ivanova, D., & Millward-Hopkins, J. (2021). Global redistribution of income and household energy footprints: A computational thought experiment. Global Sustainability, 4, e4. https:// doi.org/10.1017/sus.2021.1 Parrique, T., Barth, J., Briens, F., Kerschner, C., Kraus-Polk, A., Kuokkanen, A., & Spangenberg, J.H. (2019). Decoupling debunked: Evidence and arguments against green growth as a sole strategy for sustainability. European Environmental Bureau. Princen, T., Miniates, M., & Conca, K. (2002). Confronting consumption. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. Princen, T. (2003). Principles for sustainability: From cooperation and efficiency to sufficiency. Global Envi-ronmental Politics, 3(1), 33–50. https://doi.org/10.1162/152638003763336374 Pungas, L., Kolínský, O., Smith, T.S.J., Cima, O., Fraňková, E., Gagyi, A., Sattler, M., & Sovová, L. (2024). Degrowth from the East – between quietness and contention. Collaborative learnings from the Zagreb Degrowth Conference. Czech Journal of International Relations, 59(2), 79–113. https://doi.org/10.32422/ cjir.838

Riefler, P., Baar, C., Büttner, O.B., & Flachs, S. (2024). What to gain, what to lose? A taxonomy of individual-level gains and losses associated with consumption reduction. Ecological Economics, 224, 108301. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2024.108301

Rockström, J., Gupta, J., Qin, D. et al. (2023). Safe and just earth system boundaries. Nature, 619, 102–111. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-06083-8.

Rockström, J., Steffen, W., Noone, K., Persson, Å., Chapin, F.S., Lambin, E., Lenton, T.M., Scheffer, M., Folke, C., Schellnhuber, H.J., Nykvist, B., de Wit, C.A., Hughes, T., van der Leeuw, S., Rodhe, H., Sör-lin, S., Snyder, P.K., Costanza, R., Svedin, U., Falkenmark, M., Karlberg, L., Corell, R.W., Fabry, V.J., Hansen, J., Walker, B., Liverman, D., Richardson, K., Crutzen, P., & Foley, J. (2009). Planetary bounda-ries: Exploring the safe operating space for humanity. Ecology and Society, 14. https://doi.org/10.5751/ ES-03180–140232 Schor, J.B. (1993). The overworked American: The unexpected decline of leisure. New York: Basic Books. Schor, J.B. (1999). The overspent American: Why we want what we don’t need. New York: Harper Perennial. Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America. (1946). Employment Act of 1946. Shove, E., Pantzar, M., & Watson, M. (2012). The dynamics of social practice: Everyday life and how it changes. London: Sage Publications. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781446250655 Skidelsky, R., & Skidelsky, E. (2012). How much is enough? Money and the good life. Revised ed. New York:

Other Press. Slobodian, Q. (2018). Globalists: The end of empire and the birth of neoliberalism. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Available at: http://www.hup.harvard.edu/catalog.php?isbn=9780674979529. Smith, T.S.J., & Reid, L. (2018). Which being in ‘wellbeing’? Ontology, wellness and the geographies of hap-piness. Progress in Human Geography, 42(6). https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132517717100 Thaler, R.H. (1980). Toward a positive theory of consumer choice. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organi-zation, 1(1), 39–60. Thaler, R.H. (2016). From cashews to nudges: The evolution of behavioral economics. American Economic Review, 106(7), 1577–1600.

Thaler, R.H., & Sunstein, C.R. (2008). Nudge: Improving decisions about health, wealth, and happiness. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. Tian, P., Zhong, H., Chen, X., Feng, K., Sun, L., Zhang, N., Shao, X., Liu, Y., Hubacek, K., 2024. Keeping the global consumption within the planetary boundaries. Nature, 635, 625–630. https://doi.org/10.1038/ s41586-024-08154-w Tsurumi, T., Yamaguchi, R., Kagohashi, K. et al. (2021). Are cognitive, affective, and eudaimonic dimensions of subjective well-being differently related to consumption? Evidence from Japan. Journal of Happiness Studies, 22, 2499–2522. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-020-00327-4.

United Nations Conference on Environment & Development (UNCED). (1992). Agenda 21: The United Nations Programme of Action from Rio. Rio de Janeiro.

UN Secretary-General, World Commission on Environment and Development. (1987). Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development. Note by the Secretary-General. Veblen, T. (1994). The theory of the leisure class. 1899. Mineola, NY: Dover. Vergragt, P.J., Dendler, L., de Jong, M., & Matus, K. (2016). Transitions to sustainable consumption and produc-tion in cities. Journal of Cleaner Production, 134, 491–501. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.05.050. Victor, P.A. (2008). Managing without growth: Slower by design, not disaster. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781848442993.

Wackernagel, M., & Rees, W. (1996). Our ecological footprint: Reducing human impact on the earth. Gabriola Island, BC: New Society Publishers. Wallnoefer, L.M. (2022). Individual-level environmental sustainability – integrating perspectives and con-cepts across Research Fields. PhD dissertation, University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences, Vienna. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.17115.75045. Wallnoefer, L.M., Svensson-Hoglund, S., Bhar, S., & Upham, P. (2024). At the intersections of influence: Exploring the structure–agency nexus across sufficiency goals and time frames. Sustainability Science, 19(3), 683–686. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-024-01467-9.

Wilkinson, R.G., & Pickett, K.W. (2010). The spirit level: Why equality is better for everyone. London: Penguin UK. Wilkinson, R.G., & Pickett, K.E. (2024). Why the world cannot afford the rich. Nature. https://doi.org/10.1038/ d41586-024-00723-3