Definition

The “attitude-behavior gap” refers to the discrepancy between people’s stated attitudes and their behavioral reactions. Attitudes are enduring positive or negative feelings toward objects, persons, or issues. They can influence a person’s behavioral intentions, which in turn drive their actual behaviors. One may assume that recognizing someone’s attitudes allows the prediction of their behavior. However, it turns out that what a person expresses as their attitude does not always translate into a corresponding behavior. This points to the phenomenon of actions not being aligned with personal dispositions – also referred to as the “value-action”, “intention-behavior”, “knowledge-attitudes-practice”, or “belief-behavior” gap.

The incompatibility between “words and deeds” is well known across the social and behavioral sciences, where people’s self-reported attitudes are not always linked to subsequent actions. This is frequently observed in behavioral domains such as diet, exercising, volunteering, or political participation. It seems to be particularly salient in ethical and green consumption, where pro-environmental attitudes seem to have a limited impact on pro-environmental behavior uptake. Accordingly, numerous studies demonstrate high numbers of consumers concerned about climate change and expressing favorable attitudes toward pro-environmental behaviors, such as buying organic foods, saving energy, or recycling. These behaviors are, however, disproportionately rare in relation to reported concerns, attitudes, and intentions. The term “30:3 syndrome/paradox” was thus coined to describe that 30% of consumers intend to buy ethical goods, while only 3% actually do.

The urgency of widespread adoption of pro-environmental and pro-social behaviors, despite increasingly reported environmental attitudes, thus points to relevant motivational and structural barriers inhibiting behavior change toward sustainable lifestyles.

History

In 1935, the central role of attitudes in understanding human behavior, and the dynamic nature of their influence upon actions, was highlighted by social psychologist Gordon Allport. With the emerging consumer society in the 1940s and 1950s, consumer preferences were often assessed to predict purchase decisions, but interferences from situational, economic, or social factors were also already considered. Festinger’s Cognitive Dissonance Theory (published 1957) suggested that consumers realizing a disparity between their attitudes and behaviors might experience cognitive dissonance (i.e., psychological discomfort resulting from holding conflicting beliefs, attitudes, or behaviors, prompting a motivation to reduce this inconsistency). To reduce the dissonance, individuals might use various justifications and neutralization techniques, including moral licensing. To stimulate actual behavior change, Katz in 1960 proposed a functional approach to studying attitudes and interventions targeting and highlighting the utilitarian or social benefits of change.

With growing public environmental concern and the rise of social movements in the 1960s and 1970s, the absence of respective actions in energy conservation, recycling, or ethical consumption became increasingly evident. In the 1980s and 1990s, the relationship between attitudes and behaviors was conceptualized in behavioral theories (e.g., Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA), Planned Behavior (TPB), the Norm Activation- and Value-Belief-Norm Theory) and later empirically validated. Still, certain behaviors, particularly sustainable ones, remained inconsistent with predictions based on attitudes. Works that initially described the green gap as an unexpected deviation were soon followed by studies exploring its reasons (e.g., Kollmuss & Agyeman, 2002) and identifying methods to narrow or close it.

Different Perspectives

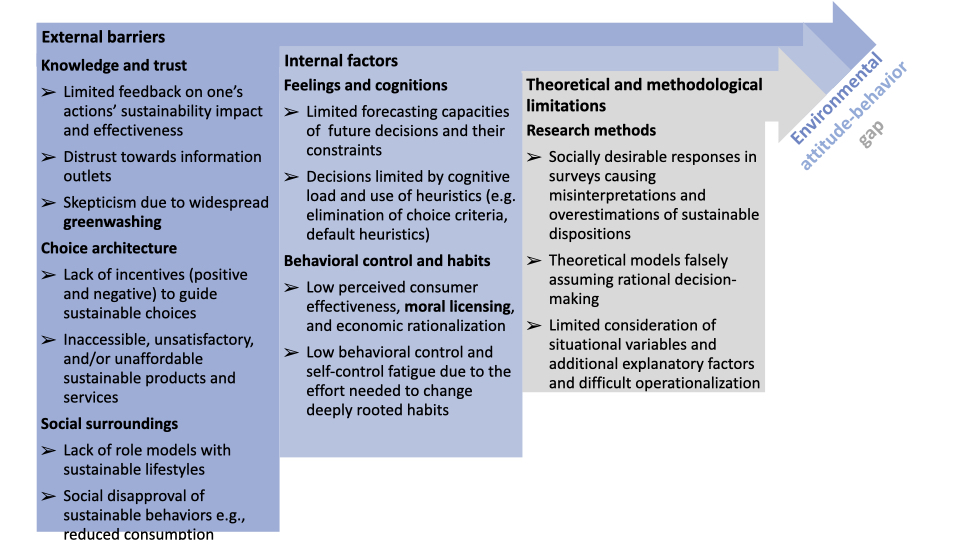

There are different positions regarding what causes the attitude-behavior gap and how to effectively close it. The most frequently discussed causes (summarized in Figure 8.1) include external barriers (primarily structural), internal factors (mainly motivational), and methodological and theoretical issues.

Source: Burgiel-Szewc & Wallnoefer (2024)

Methodological sources of the gap lie in the deficiencies of research methods, that is, in the use of self-reported measures (based on respondents’ declarations; see Lange, 2022). Meanwhile, a social desirability bias is increasingly likely since environmental concerns have become something of a trendy “must-feel”, leading respondents to overestimate the importance of ethical or ecological considerations in their decisions.

Other experts argue that many people genuinely intend to make more pro-environmental decisions and are sincere in their declarations but often overlook constraints that may distort the implementation of their original intentions. Florian Kaiser and colleagues interpret such verbal expressions of attitudes as people’s commitment to a goal and thus low-cost behaviors, while subsequent actions represent high-cost behaviors. This perspective shifts the focus from the gap between attitudes and behaviors to the balance of an environmental attitude’s strength and behavior’s costs, which can facilitate or hamper actions. A further stream of research argues that TPB-based models are incomplete because they neglect the influence of situational factors encountered by people as they move from attitude and intention to action.

In parallel, developments in behavioral economics suggested that theories assuming human rationality (e.g., TPB) cannot effectively explain all forms of behavior. This stimulated a deeper exploration of the psychological causes of the gap, including heuristics (mental shortcuts that simplify decision-making) and cognitive biases (recurring errors in thinking that distort perceptions and interpretations of information and lead to undesirable or illogical decisions).

These observations have two key implications: firstly, they have motivated a search for other factors and variables (i.e., situational, contextual, motivational, structural) that should be included in the previously used models, and secondly, they have shifted attention to alternative theories (e.g., Social Cognitive Theory, Cognitive Dissonance Theory, Dual Action Model) to study the attitude-behavior gap.

Application

In research, the attitude-behavior gap might be narrowed by addressing key methodological challenges. However, the critical remedy for bridging the gap involves behavioral change interventions that should enable and motivate consumers to align their actions with stated pro-environmental attitudes. Table 8.1 provides brief insights into recommended actions for the main actor groups to address the key causes of the gap while considering conceptual challenges.

The implementation and impact of the above measures depend on the collaborative effort of individuals in their various roles (as consumers, citizens, or role models), businesses, and policymakers. Businesses may encounter tensions between consumers’ expressed preferences for sustainable consumption and actual demand, which could hinder the development of sustainable product offerings.

The broad set of proposed measures reflects the multiple entry points to sustainable consumption. It may offer different actors more flexibility in selecting the most promising actions and studying their effectiveness and appropriateness in transdisciplinary research projects.

| Causes of a gap | Conceptual considerations | Exemplary actions recommended for individual, corporate, institutional, and governmental actors |

|---|---|---|

| Feelings and cognition | Climate anxiety, concerns, and optimism both motivate action or inhibit it due to the risk of biased information processing | I. Reframe Communication:

|

| Behavioral control and habits | Unsustainable behaviors are often habitual (i.e., repeated, automatic, and context-dependent), and demand time and effort to change | I. Adapt choice architecture (see Choice Editing):

|

| Knowledge and trust | Acceptance of information depends on the information source (e.g., experts vs. peers), dissemination channel, and media coverage | I. Build trust and credibility to overcome misinformation:

|

| Social surrounding | Social norms can influence behavior effectively if they are widely visible and supported by one’s social environment | Display (salient) sustainable social norms:

|

| Choice architecture | Sustainable product and service alternatives are often inaccessible and/or not affordable | Increase the accessibility and affordability of sustainable choices through:

|

| Research methods | Methodological shortcomings and misguided research can result from the increased social desirability of sustainable attitudes and behaviors | Adjust research methodology:

|

Further Reading

Carrington, M.J., Neville, B.A., & Whitwell, G.J. (2010). Why ethical consumers don’t walk their talk: Towards a framework for understanding the gap between the ethical purchase intentions and actual buying behaviour of ethically minded consumers. Journal of Business Ethics, 97(1), 139–158. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-010-0501-6.

ElHaffar, G., Durif, F., & Dubé, L. (2020). Towards closing the attitude-intention-behavior gap in green consumption: A narrative review of the literature and an overview of future research directions. Journal of Cleaner Production, 275, 122556. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.122556.

Govind, R., Singh, J.J., Garg, N., & D’Silva, S. (2019). Not walking the walk: How dual attitudes influence behavioral outcomes in ethical consumption. Journal of Business Ethics, 155(4), 1195–1214. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-017-3545-z.

Kollmuss, A., & Agyeman, J. (2002). Mind the gap: Why do people act environmentally and what are the barriers to pro-environmental behavior? Environmental Education Research, 8(3), 239–260. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504620220145401.

Lange, F. (2022). Behavioral paradigms for studying pro-environmental behavior: A systematic review. Behavior Research Methods, 55(2), 600–622. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-022-01825-4.