Definition

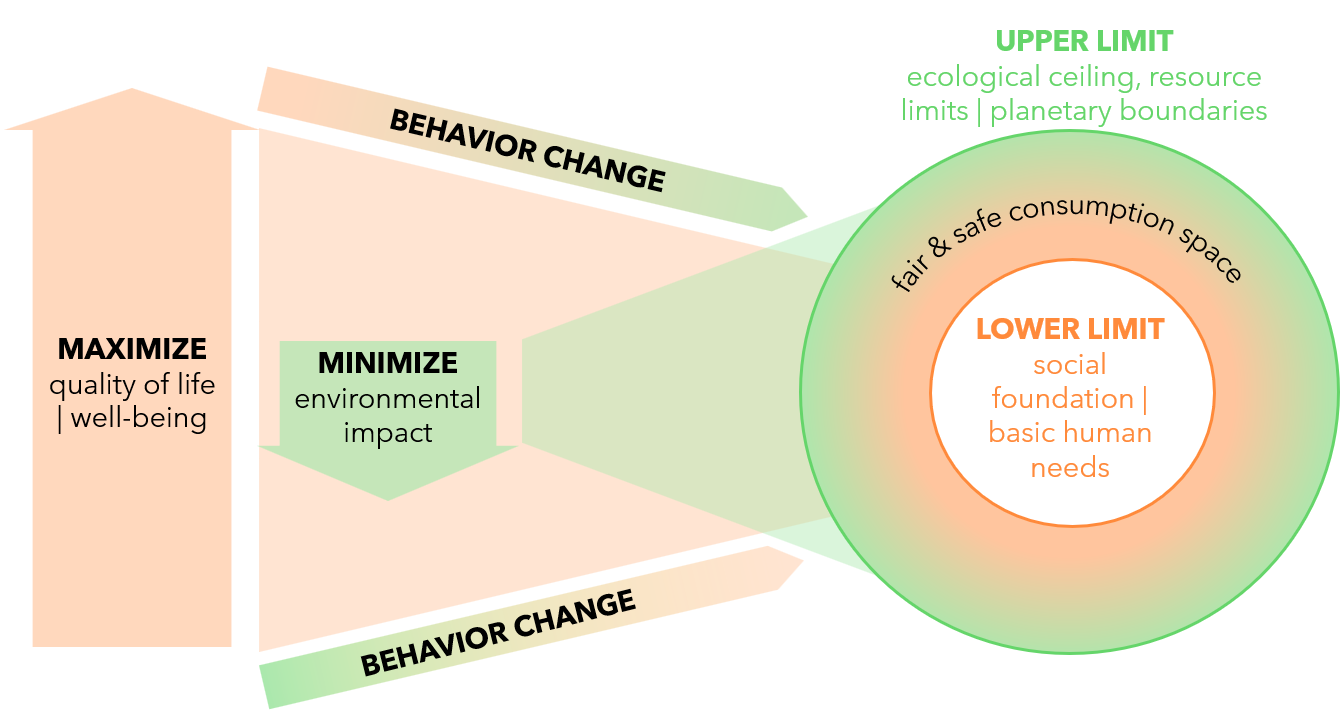

Behavior change within sustainable consumption and lifestyles refers to the transformation of peoples’ actions and choices to minimize direct or indirect sustainability impacts and maximize personal and collective well-being.

To reduce these impacts, a combination of efficiency, shift, and sufficiency strategies is advocated (see Box 9.1). Efficiency strategies focus on improved use of per-unit inputs, such as choosing energy-efficient appliances and fuel-efficient vehicles. Shift strategies involve changing from unsustainable behaviors, like eating meat, to more sustainable options, like plant-based proteins (see Protein Shift). Sufficiency strategies aim to reduce overall consumption levels, such as decreasing or avoiding travel by plane or car.

Behavioral changes to address unsustainable consumption levels and patterns are shaped by people’s motivations and the surrounding socio-structural context. Factors such as attitudes, norms, infrastructure, production systems, technology, institutions, and regulations can either hinder or promote sustainable consumption behaviors (see Social Norms, Urban Planning and Spatial Allocation, Sustainable Mobility, Sustainable Housing, Product-Service Systems, Information and Communication Technology, Choice Editing, Co-Benefits of Climate-Policy, Political Economy of Consumerism). Therefore, behavior change interventions employ techniques that target both motivational and contextual elements. These interventions can be designed and implemented by institutional actors (e.g., through regulations or campaigns), corporate actors (e.g., social marketing, see The Role of Business), and individual actors (e.g., goal-setting and implementation intentions).

History

Amidst the environmental crises of the 1960s and 1970s, reports such as Limits to Growth and campaigns like the first Earth Day brought attention to the implications of post-war mass production and consumption, the rise of consumer society, and its resulting consumer behaviors.

In the 1980s, the Brundtland Report called for new behavioral norms and values change, as products were increasingly linked to aspirational lifestyles (see Conspicuous/Positional Consumption). At this time, consumption was increasingly fueled by credit expansion (see Money, Consumerism).

In the 1990s, policies and businesses promoted efficiency strategies to improve production processes and product design while raising consumers’ environmental awareness and willingness to pay premium prices for eco-efficient products (see Ecodesign). Information provision, seen as a key intervention, followed theories linking information, attitudes, values, and behavior in a stepwise change process (e.g., Theory of Planned Behavior). Consequently, tools such as ecolabeling and information campaigns gained prominence.

However, the limitations of these interventions soon became apparent with the “attitude-behavior gap”, contradicting the information-deficit hypothesis. One response was social practice theory, which gained prominence in social sciences in the early 2000s. This theory emphasizes the interplay of meanings (e.g., norms), material objects, and competencies (e.g., bodily activities) in shaping people’s diets, water use, or commute.

Nudging, popularized in 2008 by Thaler and Sunstein, attempts to make desired behaviors the easy default option through interventions in the physical and social environment, for example, by rearranging the choice architecture and eliciting social norms (e.g., about hotel towel use) (see Green Nudging). It is particularly effective when individuals are engaged in habitual activities such as buying daily groceries.

The social context, including peers and social groups, gained prominence as a behavioral determinant, especially through its increased visibility in social media. Consequently, social marketing strategies and prompts were integrated into campaigns and movements like Transition Towns (see Social Movements). Many intentional communities began using social media to engage their members and the public in more sustainable living (see Eco-Communities, Voluntary Simplicity).

In the 2010s, the focus moved from changing individual behaviors to lifestyles. The Paris Agreement brought the understanding that 1.5°C lifestyles must ensure maximum well-being with minimal environmental and social impacts (see Well-being Economy). The new focus moved beyond efficiency and shift strategies toward sufficiency strategies. These aim at (i) staying below planetary boundaries by minimizing environmental impact and (ii) staying above minimum social thresholds of basic human needs satisfaction by maximizing quality of life (Figure 9.1; see Consumption Corridors, Doughnut Economy, Fair Consumption Space).

Different Perspectives

Understanding behavior change in sustainable consumption requires considering various perspectives on behavioral determinants, intervention effectiveness, techniques, strategies, and the actors involved. Realizing efficiency, shift/consistency, and sufficiency strategies (Box 9.1) demands the agency of different actors, including individuals, industrial, corporate, and institutional players, to change their behaviors and facilitate change in others. Responsibility for behavior change often shifts among these actors, who hold differing degrees of power over behavioral determinants.

Source: Figure designed by Laura Maria Wallnöfer for this publication

Behavior change and system change are often framed as separate approaches to sustainability, with one focusing on individual actions and the other on technological, built-environment, and regulatory contexts. Therefore, an integrated view of contextual and motivational determinants is essential in the intervention design and strategy implementation. Contextual determinants, such as infrastructure, products, services, economic incentives, and regulations, fall under the influence of institutional or corporate actors (top-down). Motivational determinants, including attitudes, values, social norms, and self-efficacy, are often within individuals’ influence (bottom-up). Effective interventions help individuals to overcome obstacles, related to money, time, and/or effort, enabling them to adopt desirable behaviors. They focus on behavioral skills, like adhering to implementation plans, rather than relying on less effective determinants like knowledge and beliefs.

Behavior change is limited when motivations – such as the willingness to buy and use efficient products, modal shifts from driving to cycling, and meat consumption reduction – are not supported by structures that are available, accessible, and affordable. Conversely, if institutions and corporations provide these structures but fail to generate sufficient motivation among individuals, behavior change remains inhibited due to the attitude-behavior gap or entrenched habits. The bottom-up actions of individuals, households, and communities must thus be accompanied by top-down efficiency, shift, and sufficiency actions in production, infrastructure, and regulations to enable a functioning structure-agency nexus.

Applications

Efficiency-, shift-, and sufficiency-oriented behaviors for sustainability require a multi-actor process and evidence-based interventions. Socio-psychological, industrial, and political insights should guide these efforts based on environmental effectiveness, societal acceptance, and scalability to encourage actors to become change agents in their spheres of influence (see Box 9.1).

Box 9.1 Examples of entry points for inducing behavioral change through the target strategies: efficiency, shift, and sufficiency

| Strategy | Efficiency: improving consumption quality | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Behavior change | Adopting better alternatives of products and services | ||

| Effect | Mitigating negative impacts within the current technological paradigm through green innovation and product and process improvements | ||

| Action fields | Greening Markets: providing efficient products and consumer education, considering gender and income disparities in environmental impact | Communication and Advertising:promotion and mainstreaming, considering greenwashing and consumer awareness | Choice Editing and Nudging:Rearranging choice architecture to reduce the need for additional information to guide behavior |

| Interventions | Ecolabels, reframing plant-based diet, gender-connotations, Austria’s Mission 11 energy-saving campaign | Restricting adverts for fossil-fuel-intensive products,EU’s greenwashing regulation | Meatless Mondays (sustainable option as default), store layout, menu design |

| Actors | Policymakers: transparent labeling, energy-saving campaigns, and efficiency regulationsCorporations: innovate for better input-output ratios and effective label useConsumers: informed choices about resource efficiency and purchase eco-efficient products, supported by certified labelsIn 2019, 29% of Europeans viewed technological improvements as the best climate mitigation strategy | ||

| Strategy | Shift: changing consumption patterns | ||

| Behavior change | Shifting to alternative business models and provision systems | ||

| Effect | Changing consumption patterns by questioning needs and wants, e.g., the shift from ownership to shared use (see Sharing Economy) | ||

| Action fields | Social Practices: habits and social norms (meanings) | Innovative Business Models: circular and sharing economy models, enabling individuals to transition from consumers to prosumers | Socio-Technical Systems: infrastructures, and institutions |

| Interventions | Showers at workplaces for cyclists, gamification, rewards, implementation plans | Sharing apps, financial incentives for circular behaviors (see Circular Economy and Society) | Multimodal mobility offers, taxation, sustainable urban planning and procurement practices |

| Actors | Policymakers: providing infrastructure and enabling regulations, creating an environment conducive to business model innovation.Corporations: lead by mainstreaming sustainable offers, implementing circular and sharing business models, and adding value to waste. Individuals: contribute by participating in sharing networks, providing products to share, and valuing use over ownership. | ||

| Strategy | Sufficiency: curtailing consumption volumes | ||

| Behavior change | Absolute reduction in the total levels of resource consumption and associated environmental impact, while fulfilling basic human needs and enhancing well-being | ||

| Effect | Transformative processes at a macroeconomic level toward sustainable living through “beyond the market” solutions | ||

| Action fields | Degrowth and New Economic Order: economic models prioritizing environmental sustainability and social equity over continuous economic growth, emphasizing policy reforms and cultural shifts toward sufficiency | Sufficiency and Sustainable Lifestyles: lifestyles of fulfillment and enhanced well-being without excessive consumption, based on new value systems rooted in equity and sufficiency, enabled by policy and mainstreamed through collective action | Societal Transformation and Sustainability: deepen and accelerate change through an “ecosystem of transformation” comprising deliberate policies, shifts in socio-technical systems, and social practices, supported by autonomous bottom-up actions |

| Interventions | Alternative measures to GDP, universal basic services, shorter working time (see Work-Life Balance), carbon caps | Communication Framing of reduced consumption as gain, de-marketing, utilizing windows of opportunity and disruptions to normalize a sufficiency mindset | Participatory beyond-growth conferences, increasing the visibility of changes in behavior, to potentially trigger norm changes and, thus, social tipping points |

| Actors | Policymakers: promoting growth-independent well-being and alternative economic measures (see Well-being Economy).Companies: facilitate sufficient production, extended product use, and alternative business models.Individuals: contribute by adopting less resource-intensive lifestyles.Progressive top-down approaches to facilitate radical individual behavior changes were considered the best climate mitigation strategy by 39% of Europeans in 2019, while 14% preferred strong regulation. | ||

Each strategy uniquely contributes to sustainability transitions, with examples spanning individual behaviors, market and business innovations, and systemic transformations. The interplay of efficiency, shift, and sufficiency strategies highlights the need for concerted efforts across societal, economic, and institutional dimensions.

Further Reading

Jackson, T. (2005). Motivating sustainable consumption – A review of evidence on consumer behaviour and behavioural change (Issue December). Available at: http://www.sd-research.org.uk/researchreviews/documents/MotivatingSCfinal.pdf (accessed: 7 January 2025).

Klaniecki, K., Wuropulos, K., & Hager, C. (2019). Behavior change for sustainable development. In L. Filho (Ed.), Encyclopedia of sustainability in higher education. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-63951-2_161-1.

Mont, O., Lehner, M., & Dalhammar, C. (2022). Sustainable consumption through policy intervention – A review of research themes. Frontiers in Sustainability, 3. https://doi.org/10.3389/frsus.2022.921477.

Newell, P., Twena, M., & Daley, F. (2021). Scaling behaviour change for a 1.5-degree world: Challenges and opportunities. Global Sustainability, 4. https://doi.org/10.1017/sus.2021.23.

Thøgersen, J. (2021). Consumer behavior and climate change: Consumers need considerable assistance. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences, 42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cobeha.2021.02.008.