Definition

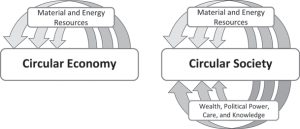

In the last decade, the concept of the circular economy (CE) has emerged as a major discourse on sustainability in policy, business, NGO, and academic domains. While the concept of the circular economy (CE) continues to evolve, encompassing a plurality of approaches, the main idea is to optimize the use of the Earth’s natural resources to meet human needs in a sustainable, resilient, and regenerative manner. CE thereby seeks to create a balanced and harmonious flow of socio-ecological resources between human and natural ecosystems so humanity may thrive within planetary boundaries. There are two broad conceptualizations of circularity: a CE, which only seeks to circulate material and energy resources sustainably, and a Circular Society (CS), which also seeks to circulate wealth, political power, care, and knowledge (including technologies) in a democratic and redistributive manner (see Figure 49.1).

Source: Adapted from Calisto Friant et al. (2020, 2024)

History

The idea of a CE is nothing new. For the greatest part of humanity’s presence on Earth, material and energy flows were in harmony with the Earth’s regenerative capacities. It is only with the rise of capitalism and the Industrial Revolution that humanity permanently broke this balance through the increasing use of fossil fuels, colonization, and the global dominance of growth-dependent economic systems.

The CE concept arose as a response to these socio-ecological crises and had various stages and phases in its development, summarized in Table 49.1. Considering the diverse history and the variety of concepts related to CE, it is best understood as an “umbrella concept” that combines and embraces many key elements of sustainability thinking.

The 1960s and 1970s were the first significant moments in CE development when many of the modern precursors to the CE concept emerged, driven by a rising awareness of the impossibility of eternal economic growth on a finite planet (see Degrowth). A myriad of ideas were put forth for post-capitalist socio-economic systems that do not depend on economic growth to survive (e.g., ecoanarchism, steady-state economics, and Buddhist economics; see “precursors” in Table 49.1). They proposed a wholesale transformation of our production and consumption systems to create slower and more convivial ways of life centered on non-material aspirations. This coincided with the emergence of global environmental movements and the institutionalization of environmental protection (e.g., in the 1972 United Nations Conference on the Human Environment and the creation of UNEP).

During the 1990s to early 2000s, neoliberal thinking dominated global debates and centered on market-based approaches to CE, focusing on economic growth, technological innovation, and competitive markets as avenues to address social and environmental problems (see, e.g., Extended Producer Responsibility). However, particularly in the 1990s, little attention was paid to social justice issues or systemic transformations to reduce unsustainable production and consumption patterns.

In the 2000s, new CE concepts – with a more holistic and socially inclusive approach to consumption and production – were developed, such as Cradle-to-Cradle, the Performance Economy, Doughnut Economics, as well as Degrowth. In addition, several transformative concepts from the Global South emerged during this time, such as Buen Vivir and Buenos Convivires by Latin American Indigenous movements, Ecological Swaraj in India, and Ubuntu from South Africa. These movements stress the importance of global justice and decolonization for a just transition and place Mother Earth as an equal partner endowed with inalienable rights.

During the same time, many national governments, such as China, Japan, and the EU, as well as cities such as Paris, Amsterdam, and London, started incorporating CE into their policies. This is also the moment when many corporations around the globe integrated the CE concept as part of their sustainability and corporate social responsibility strategies, such as Unilever, IKEA, Patagonia, Renault, Fairphone, and Swapfiets.

Different Perspectives

A circularity discourse typology was developed to help navigate the rich history and diversity of CE concepts and ideas, dividing the discourses into two main criteria. First, it distinguishes segmented discourses, which focus on the technical and business components of circularity, from holistic discourses, which include social justice and political empowerment. Second, it divides optimist and skeptical perspectives regarding the possibility of decoupling environmental degradation from economic growth. Different combinations of these two criteria lead to four main circularity discourse types (Table 49.2).

Research on CE has found that the most dominant and widespread discourse type is currently the Technocentric Circular Economy. Over 80% of CE definitions fall in this discourse type, which is particularly widespread in business consultancies and corporate CE strategies. Governments and the EU tend to follow a more mixed approach with some holistic discursive elements that, however, often fail to translate into more sustainable and socially inclusive policies.

| Circularity 1.0 ana 2.0: lecnno-nxes to waste | Circularity 3.0: integrated socio-economic approaches to resources, consumption ana waste | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Precursors to circularity | Circularity 1.0: Dealing with Waste | Circularity 2.0: Connecting Input and Output in Strategies for Ecoefficiency | Circularity 3.1 Reformist views on Circularity | Circularity 3.2 Transformational views on Circularity and visions of the Global South | ||

| Preamble Period | Excitement Period | Validity Challenge Period | ||||

| 1945–1980 | 1980–2010 | 2010 to present | ||||

| Gandhian economics (1945) | Waste-Water Treatment | Industrial Ecology | First holistic Circularity frameworks | New holistic Circularity views | Transformational views of Circularity | Non-western visions of Circularity |

| The Economics of the Coming Spaceship Earth (1966) | Solid Waste Management and Recycling | Ecodesign/Design for environment | Rio Declaration on Environment and Development (1992) | Blue Economy (2010) | Transition Movement (Hopkins, 2008) | Buen Vivir/ Sumak Kawsay |

| The tragedy of the Commons (1968) | Bio-Digestion | Cyclic Economy (1993) | Regenerative design (1994) | Third IndustrialRevolution (2013) | Degrowth | Ubuntu |

| The Population Bomb (1968) | Energy Recovery | Industrial Metabolism (1994) | Natural Capitalism(1999) | Ecosystem Economy (2013) | Ecosocialism | Ecological Civilization |

| Bioeconomics of Georgescu-Roegen (1971) | Cleaner Production | Cyclical Economy (2001) | Regenerative Capitalism (2015) | Low-Tech | Ecological Swaraj | |

| The Closing Circle (1971) | Reverse Logistics | Materials Matter (2001) | Sharing Economy | Laudato si’ (2015) | Suma Qamaña / Vivir Bien | |

| Ecoanarchism (1971) | Ecoindustrial parks and networks | Cradle to Cradle(2002) | Doughnut Economics (2017) | Transition design (2015) | Buddhist, Confucian and Taoist ecology | |

| The Limits to Growth (1972) | Biomimicry (1998) | The Natural Step(2002) | Symbiotic Economy (2017) | Economy for the Common Good (2015) | Radical Pluralism/Pluriverse | |

| Ecological Design (1972) | Product Service System | The PerformanceEconomy (2010) | Social Circular Economy (2017) | Post-growth | ||

| United Nations Conference on the Human Environment (1972) | Extended Producer Responsibility | Sound Material-Cycle Society in Japan (2000) | Spiral Economy (2019) | Permacircular Economy (2018) | ||

| Buddhist economics (1973) | Industrial Symbiosis | Circular Economy in China (2002) | Coviability (2019) | Voluntary Simplicity | ||

| Conviviality (1973) | Closed-loop Supply Chain | EU Circular Economy Action Plan (2015) | Circular Humansphere (2019) | Convivalism (2019) | ||

| Steady-state economics (1977) | Biobased Economy/Bioeconomy | |||||

| Permaculture (1978) | The Biosphere Rules (2008) | |||||

| Décroissance (1980) | ||||||

| Deep Ecology (1980) | ||||||

| Overshoot (1980) | ||||||

| Approach to social, economic, environmental, and political considerations | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Holistic | Segmented | ||

| Technological innovation and ecological collapse | Optimist | Reformist Circular Society

|

Technocentric Circular Economy

|

| Skeptical | Transformational Circular Society

|

Fortress Circular Economy

|

|

In response to the dominance of technocentric propositions, there is a rising movement promoting a holistic CS vision, especially in European civil society. CS visions are gaining greater support, especially from those who have criticized mainstream CE propositions for focusing too much on economic growth and competitiveness and too little on social and environmental justice. Indeed, many see hegemonic CE propositions as forms of greenwashing, which create the illusion that “green technologies” will allow us to overcome the biophysical limits of the Earth and continue growing our economies forever (i.e., weak sustainability). Yet, over 50 years of academic evidence show that decoupling economic growth from environmental degradation is impossible on a relevant scale to prevent biodiversity collapse and climate breakdown.

The current domination of technocentric approaches to circularity has curtailed the possibility of a more plural and democratic debate regarding what circular future we want and how we want to get there. Indeed, many governments and businesses have preferred to adopt a depoliticized and uncontroversial CE approach that does not address fundamental issues regarding social equity, political empowerment, and the biophysical limits to economic growth. This prevents tackling key questions, such as who owns CE technologies and innovations, who should reduce their production and consumption levels in line with planetary boundaries, and who should pay and govern the transition. Thus, the dominance of Technocentric CE discourses suppresses alternative discourses and concepts such as degrowth, post-growth, care economics, and post-humanist ideas that highlight the rights of nature and the need for systemic socio-ecological transformations (see Box 49.1).

Moreover, research has shown that grassroots and civil society organizations tend to have a more holistic and socially inclusive vision of circularity than the Technocentric paradigm that governments and companies are implementing (see Grassroots Innovation and Alternative Consumer Cooperatives). Indeed, surveys have found that people in OECD countries prefer a sufficiency-oriented ecological transition that prioritizes human and ecological well-being rather than profits.

Box 49.1. Status and outlook of CE – moving from a “validity challenge” period to more holistic CE discourses

The CE is in what Blomsma and Brennan call a “validity challenge” period; this means that it must confront its key challenges and limitations to remain relevant. If the CE debate remains stuck in “fairy tales” of “green growth” and doesn’t embrace a strong socio-ecological justice agenda, it will lose its social appeal and systemic validity, especially considering the rising inequalities and injustices brought by over 30 years of neoliberal globalization. As we continue to overshoot the ecological limits of the biosphere and the impacts of climate change rise year after year, it will become harder and harder to argue for failed technocentric solutions.

Systemic socio-political change to post-growth circular societies will be necessary, whether we like it or not. Yet, faced with an impending socio-ecological collapse, visions of a Fortress CE will also become more and more appealing. Indeed, as we confront stronger natural disasters and shortages of crucial natural resources, many conservative voices could start arguing for greater nationalism and top-down control over resources and populations. This is already happening today with the rise of far-right movements, and it may become more prevalent in the future. To prevent this, it is key to expand the discussion and shift our debate from narrow visions of a CE to more holistic CS discourses. Improving transformative learning to build “circular literacy” and democratic co-design processes may help develop a greater understanding of the diversity of circularity approaches and break the current dominance of technocentric visions (see Education for Sustainable Consumption).

| Transforming cultural practices | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Refuse | Re-evaluate | Rethink | Re-conceptualise | ||||

| Buying, producing or using less and avoiding over-consumption and over-production. | Reconsidering values and worldviews, e.g. from consumerism to sufficiency, from egoism to solidarity | Rethinking how value chains are organized and phasing out linear structures, incentives and mindsets | Redefining the meaning of a good life and shifting away from endless and senseless materialist and individualist aspirations | ||||

| Transforming economic practices | |||||||

| Redesign | Reduce | Restructure | Redistribute | Re-localise | Reuse | Restore | |

| Redesigning products and services to improve socio-ecological sustainability | Using less material per production unit (e.g. smaller/lighter product) | Transforming social, political and economic systems to align with the values of a circular society | Redistributing power, technology, knowledge and access to resources, both between and within countries | Producing near consumption centres, a re-localising politics, culture and the meaning of life | Using second-hand products, reusing packaging, sharing goods | Restoring natural ecosystems or cultural heritage to their original or improved condition (also called “regenerate”) | |

| Transforming material practices | |||||||

| Replace | Repurpose | Repair | Refurbish | ReManufacture | Recycle | Re-mine | Recover(energy) |

| Substituting polluting and toxic materials or chemicals for safe and sustainable ones | Adapting discarded things for another function, such as rubber tyres as fences | Restoring functionality of products, fixing defects | Improving components of a product (also called “reconditioning” or “retrofitting”) | Disassembling, checking, cleaning, and repairing in an industrial process (also called “reprocessing” or “re-assembling”) | Processing waste products to obtain “secondary raw materials” | Recovering natural resources from landfills | Capturing energy embodied in waste through incineration or bio-digestion |

Application

As seen above, there are multiple diverging approaches to a circular economy and society, depending on the interests and objectives of different actors that implement them. To summarize the diverse forms of CE application, Table 49.3 presents a list of the 19 value retention options (also known as Rs), which are the core strategies used in CE implementation. They are divided into three interdependent and interrelated types of socio-ecological transformation: cultural (underlying worldviews and values), economic (social provisioning and distribution systems), and material (production, consumption, and recovery structures).

The above list attempts to provide a comprehensive list of how circularity may be applied at various social, political, and business levels. However, it is in no way exclusive nor exhaustive, so different actors may implement a specific selection of strategies in the list or may develop entirely new strategies not listed above.

Further Reading

Calisto Friant, M., Vermeulen, W.J.V., & Salomone, R. (2024). Transition to a sustainable circular society: More than just resource efficiency. Circular Economy & Sustainability, 4, 23–42. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43615-023-00272-3.

Genovese, A., & Pansera, M. (2021). The circular economy at a crossroads: Technocratic eco-modernism or convivial technology for social revolution? Capitalism, Nature, Socialism, 32(2). https://doi.org/10.1080/10455752.2020.1763414.

Hempel, N., Boch, R., & Jaeger-Erben, M. (2023). Co-designing a circular society. In Design for a sustainable circular economy: Research and practice consequences, pp. 205–232. Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-99-7532-7_11.

Rask, N. (2022). An intersectional reading of circular economy policies: Towards just and sufficiency-driven sustainabilities. Local Environment, 27(10–11), 1287–1303. https://doi.org/10.1080/13549839.2022.2040467.

Suárez-Eiroa, B., Fernández, E., & Méndez, G. (2021). Integration of the circular economy paradigm under the just and safe operating space narrative: Twelve operational principles based on circularity, sustainability and resilience. Journal of Cleaner Production, 322. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.129071.