Definition

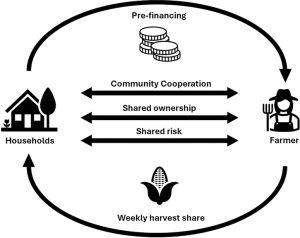

Community-supported agriculture (CSA) is a collaborative grassroots innovation, in which farmers and consumers share the costs and outputs of food production. By joining a CSA, consumers agree to cover the costs of a farming operation over a defined period, during which they gain access to a share of the harvest (see Figure 66.1).

The exact business model can differ between CSAs that are (1) run as subscription services by individual producers, (2) based on collective associations of consumers, or (3) run as integrated organizations whose members co-own the entire operation (see Alternative Consumer Cooperatives). Similarly, some of the practices in CSAs can differ: Some deliver food to members, while others require them to pick it up. Most CSAs provide uniform food shares, while some offer a choice regarding the purchased products. In some CSAs, members need to spend some time helping out on the farm. Moreover, a few CSAs engage in social activities beyond food provision, such as organizing farm visits, environmental talks, or nutritional education classes for schools (see Table 66.1).

History

CSA originated in Japan in the 1960s under the term teikei. It was connected to an organic agriculture movement and involved local consumer associations, mainly run by women, who set up food provision agreements with nearby farmers. The practice was eventually adopted by small farmers in the United States and Europe in the 1970s under the label “CSA”. However, it remained relatively unknown until the 2008 food price shock generated a wave of interest in it (Blättel-Mink et al., 2017). Since then, CSA has continuously expanded, developing thousands of local initiatives, as well as national and international CSA networks. CSA has also gained prominence in Latin America and Africa, where it became closely tied to movements for food sovereignty, such as La Via Campesina. Most recently, CSA received another boost during the COVID-19 pandemic, as disruptions in the retail sector raised people’s interest in prosumer activities.

Different Perspectives

Farmers benefit from CSA by gaining financial security and in some cases practical support. By matching food production and demand, CSA enables small farmers to avoid volatile market competition, thus raising their resilience. In turn, consumers receive access to locally produced food, and in many cases can become involved in the production process. As a business model, CSA is viewed as fostering the development of small, ecologically sustainable food supply chains and prefiguring a non-capitalist alternative to essential needs provision (Hitchman, 2016; see The Role of Business, Foundational Economy). Moreover, the practice is often praised for developing closer social ties between producers and consumers, aiming to raise people’s awareness of the need for local food systems and encouraging more environmental and healthy nutritional behaviors.

Source: By authors

On the other hand, critics of CSA highlight various shortcomings. An oft-cited problem is the practice’s relative inaccessibility, as CSA membership requires a degree of financial security and cultural capital, including nutritional awareness and cooking skills. Consequently, in most countries, CSA members are overwhelmingly white and from well-educated middle-class backgrounds, with progressive-environmentalist values (Mert-Cakal & Miele, 2020), making up a relatively small “bubble” (see Social Movements). Even among CSA members, there is usually only a small core of dedicated activists who strongly share the practice’s political principles and engage in voluntary activities, whereas the rest act as passive consumers. This raises concerns about CSA’s ability to compete with more conventional organic retailers or box schemes and, by extension, its ability to transform the food system at scale.

Conversely, in regions where multiple CSAs have clustered, they are more capable of offering a significant level of food provision, as well as connecting and diversifying their supply. However, some CSAs in such areas have also begun competing with each other, highlighting their need to attract a broader clientele in general.

Application

CSAs exist around the world, often under different names and with country-specific characteristics (see Mayer & Peréni, 2021). In francophone contexts, the practice is known as AMAP (Association pour le Maintien d’une Agriculture Paysanne – “Association for the Maintenance of Peasant Agriculture”). This constitutes the most numerous form of CSA in one country, as at the time of writing there exist over 6,000 AMAPs across France.

The US hosts the second-largest national CSA movement, counting over 2,500 enterprises. This movement has recently developed a strong focus on combating racial inequalities in CSA membership and farming. The country’s “CSA Innovation Network” has developed practical tools for integrating antiracist practices into the model, and many CSAs work particularly with farmers and communities of color.

The German CSA model, which is known as Solawi (Solidarische Landwirtschaft – “Solidarity- based Agriculture”), presents a different approach to tackling social inequalities. Most Solawis organize “bidding rounds”, in which members anonymously pledge how much money they want to contribute. If they fall short of reaching a minimum budget, members are asked to pledge again. At this point, most Solawis succeed at meeting their target. This system accommodates members with different income levels without creating a stigma of charity, thereby making CSA more accessible by practicing solidarity.

In Italy, CSA has only recently taken root, but another food prosumer practice has flourished for many years under the term GAS (gruppi d’aquisto solidale – “solidarity purchasing groups”). Such groups collectively buy food and other goods from sustainable sources, but they do not co-finance farming operations. Due to the recent spread of CSA in the country, many GAS are considering “upgrading” to what they perceive as the more ambitious model.

Moreover, the original Japanese teikei movement is still active and recently celebrated its 50th anniversary. However, its reach has declined since the 1990s, when the number of teikei groups peaked at around 300. This regression reflects a concentration of demand around fewer, more professionalized teikeis and a shift toward a more passive consumer base, indicating what risks CSA movements may face if they fail to address their shortcomings.

To help CSA grow beyond its niche, initiatives in many countries have developed country-wide CSA networks (Guerrero Lara et al., 2024). These mainly offer a way to engage in mutual learning and resource sharing, thereby helping new CSA initiatives off the ground. Some CSA networks also collaborate economically to develop common supply chains and food processing facilities, such as bakeries. Most recently, larger CSA networks also started advocating for policy changes, mainly to receive agricultural subsidies and provide CSA access to lower-income households. While most CSAs collaborate around themes of sustainable farming and food sovereignty, CSAs in Southern Europe are embedded in networks of the “social and solidarity economy”, thus connecting CSA with non-market-based economic approaches across other sectors.

To share knowledge and skills between these different national approaches, CSAs also engage in international exchange, for instance, via the LSPA MedNet (Mediterranean Network of Local Solidarity Based Partnerships for Agroecology), which brings together CSAs from Southern Europe and North Africa, as well as the international Urgenci network, which connects CSA networks across the globe and provides information about the movement’s worldwide development.

CSA is unlikely to replace dominant agricultural practices on its own, but it offers a powerful vision for how to organize more sustainable, resilient, community-based food supply chains. As such, it not only attracts consumers but could also inspire policymakers and green enterprises to develop local partnerships to grow and distribute food outside conventional market channels.

Further Reading

Blättel-Mink, B., Boddenberg, M., Gunkel, L., Schmitz, S., & Vaessen, F. (2017). Beyond the market – New practices of supply in times of crisis. The example community-supported agriculture. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 41(4), 415–421. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcs.12351.

Guerrero Lara, L., Feola, G., & Driessen, P. (2024). Drawing boundaries: Negotiating a collective ‘we’ in community-supported agriculture networks. Journal of Rural Studies, 106, 103197. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2024.103197.

Hitchman, J. (2016). How community supported agriculture contributes to the realisation of solidarity economy in the SDGs. UN Inter-Agency Task Force on Social and Solidarity Economy.

Mayer, B., & Peréni, Z. (2021). Food & More toolkit. From beginner to advanced. European Commission. Available at: https://cloud.urgenci.net/index.php/s/MsXw74WZcRRaFGt?dir=undefined&path=%2F&openfile=5519 (accessed: 8 January 2025).

Mert-Cakal, T., & Miele, M. (2020). Workable utopias’ for social change through inclusion and empowerment? Community supported agriculture (CSA) in Wales as social innovation. Agriculture and Human Values, 37(4), 1241–1260. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-020-10141-6