Definition

Consumption-based accounting (CBA) is an approach for calculating ecological and social impacts related to a particular process or product, based on its full lifecycle, including the end-use, and attributing them to the final consumer. The result is called a consumption-based footprint. This approach is complementary to so-called territorial or production-based accounting, which attributes the impacts to the location where they occur or to the producer. For instance, if a particular material good is manufactured in one location and exported elsewhere, CBA attributes its impacts to the end user, whereas territorial accounting would attribute them to where it was produced. In CBA, the entity in question can be anything from an individual to an organization, city, nation, region, or the globe. On a global level, consumption-based and territorial/production-based impacts are the same.

The endpoints measured in CBA can include carbon, biodiversity, nitrogen, water, energy, and land-use footprints in the ecological domain. Social footprint endpoints have been more scarce, but include, for example, global slavery footprint. Carbon footprints, based on carbon dioxide emissions, are the most commonly used metric. Often, a carbon footprint also includes other greenhouse gases, such as methane, normalized to carbon equivalents based on their atmospheric warming potential per unit volume. In such cases, carbon footprint becomes a de facto greenhouse gas or climate footprint.

History

CBA emerged in the late 20th century with the first consumer carbon footprint estimations. Its widespread adoption took place in the early years of the millennium, first in academia, then followed by other organizations. In 2005, British Petroleum (BP) introduced a major campaign to popularize consumption-based carbon footprints, though this move has been widely criticized as a cynical attempt by the company to emphasize the impacts of personal consumption and lifestyles on global carbon emissions (“blaming the victim”) (see Consumer Scapegoatism, Greenwashing). The campaign achieved that goal.

The consumption-based carbon footprint assessment of 79 member cities of the C40 Cities Climate Leadership Group in 2018 was an important milestone in the diffusion of CBA outside academia. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has also started emphasizing the importance of the consumption-based perspective. The 2022 Sixth Assessment Report (AR6) devoted a lot of space to mitigation options based on reduced consumption, with the Working Group III Co-Chair Priyadarshi Shukla stating in a press release that “having the right policies, infrastructure and technology in place to enable changes to our lifestyles and behaviour can result in a 40–70% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions by 2050. This offers significant untapped potential”.

On a national level, the Nordic countries have been at the forefront in recognizing the importance of the demand side – especially household consumption – in driving up global carbon emissions. In 2023, the Nordic Council of Ministers declared that

Nordic consumption must change if [the sustainable development goals] are to be achieved … Nordic consumption has a huge environmental and climate footprint in other parts of the world. The Nordic Council of Ministers is working to turn this around and make the Nordic Region the most sustainable region in the world.

However, even in the Nordic countries, there is a lack of serious commitment to take responsibility for the environmental impacts caused by them outside their territories.

Different Perspectives

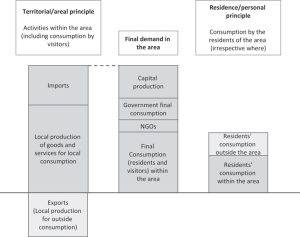

CBA is an umbrella term for two different allocation/responsibility principles. If a territorial or areal principle is followed, the impacts are allocated based on consumption within a certain location regardless of who within the area or territory is consuming. For example, if a resident of country A travels to country B on a leisure trip, all their consumption in country B would be allocated to the consumption-based carbon footprint of country B. Vice versa if a residence or personal principle is adopted, the impacts are allocated based on residency, regardless of where consumption happens. Using this principle, the consumption by the resident of country A on a leisure trip to country B would be counted in the consumption-based carbon footprint of country A. These definitional differences mean that when looking at geographic areas – such as a city or a nation – the territorial/areal principle shows higher impacts where tourists and commuters are responsible for an important share of all demand for goods and services. In turn, it is lower where there are no tourists or where the residents commute away for work, school, and errands. On the other hand, the residence/personal principle shows how the impacts follow personal consumption, even when that consumption takes place outside the home location.

CBAs are often divided into three main domains: personal/private consumption, governmental consumption, and capital production. With the territorial/areal principle, it is clear that the boundaries of the assessment coincide with the area in question, plus imports and minus exports. With the residence/personal principle, the scope is different. The personal/private consumption component includes only the activities of the residents of the area in question and excludes those of visitors to the location. The personal/private consumption component therefore consists of the consumption of residents and visitors within the area in question if using the territorial/areal principle, but of the consumption of residents within and outside the area in question if using the residence/personal principle.

Governmental consumption always serves a particular location (e.g., green spaces, safety and waste collection services) and, therefore, benefits both residents and visitors. This means that governmental consumption is very difficult to include in the residence/personal principle. Using the residence/personal principle, governmental consumption would partially consist of local governmental consumption, but also partially of governmental consumption in all the locations visited outside the home location. It would also include governmental consumption serving the production of goods and services consumed by the individuals in question.

Similarly, with the territorial/areal principle, capital production can be allocated to the location in question using the same allocation method as with governmental consumption. With the residence/personal principle, allocation of capital production is again difficult.

Source: Adapted from Heinonen et al. (2020)

Due to these allocation problems, the scopes of the two CBA approaches typically become very different from one another, and therefore a reader should not compare the results when the allocation principle has not been the same.

Figure 85.1 shows how the territorial/areal principle captures the global impact of the area in question, and how that matches with final demand in the area, whereas the residence/personal principle captures the global impact caused by the residents of the area in question.

Application

While CBA has not gained much popularity in policymaking, there are signs of change. Accordingly, Sweden recently announced a target to become the first nation to include the impacts caused by their societies outside their territories in their carbon neutrality targets. Sweden and Finland have also started publishing national greenhouse gas emissions accounts based on CBA to inform citizens and policymakers. In Finland, a recent national CBA analysis concluded that with the right policies, consumption-based carbon footprints could be reduced by 50% by 2035. Iceland is trying to map its so-called spillover effects, that is, the effects occurring beyond its territory, but induced by its economy.

On a city level, in the United States, Portland, Oregon, and several other cities have adopted consumption-based greenhouse gas accounts as companions to their territorial inventories. Portland’s CB Inventory in 2011 showed that the city’s consumption-based emissions are 40% greater than the emissions based on territorial accounting.

Another application of CBA is the use of mobile apps that provide consumers with information about the carbon footprint of their purchases at the point of transaction. In the future, CBA could be very useful for allocating responsibility among nations for developing effective climate policies and for setting long-term targets, based on the emissions driven by each country’s consumption. Accounting with metrics other than greenhouse gases – for example, biodiversity footprints – would be also valuable for allocating responsibility.

The adoption of CBA in policymaking, however, encounters barriers and complications. First, current assessment techniques do not lead to precise estimates and contain high uncertainty, which may create political tensions. Second, in the cases where a large portion of emissions is imported, controlling the impacts outside the jurisdictional area of a country is complicated, for example, if the country of origin is highly fossil-fuel dependent (see Carbon Inequality).

Moreover, if the CBA analysis points toward the need to curb consumption, the political willingness to adopt such policies is typically low (see Political Economy of Consumerism, Degrowth). In contrast, territorial accounting naturally draws attention to the need to improve the efficiency of production, transition away from fossil fuels, and overall technological innovations. Such policies are more straightforward to implement and are politically easier to pursue.

Further Reading

Afionis, S., Sakai, M., Scott, K., Barrett, J., & Gouldson, A. (2017). Consumption-based carbon accounting: Does it have a future? Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change, 8(1), e438. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.438.

Heinonen, J., Ottelin, J., Ala-Mantila, S., Wiedmann, T., Clarke, J., & Junnila, S. (2020). Spatial consumption-based carbon footprint assessments – A review of recent developments in the field. Journal of Cleaner Production, 256, 120335. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.120335.

Ivanova, D., Stadler, K., Steen-Olsen, K., Wood, R., Vita, G., Tukker, A., & Hertwich, E. (2016). Environmental impact assessment of household consumption. Journal of Industrial Ecology, 20(3), 526–536. https://doi.org/10.1111/jiec.12371.

Malik, A., McBain, D., Wiedmann, T., Lenzen, M., & Murray, J. (2018). Advancements in input-output models and indicators for consumption-based accounting. Journal of Industrial Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1111/jiec.12771.

Wilting, H., Schipper, A., Bakkenes, M., Meijer, J., & Huijbregts, M. (2017). Quantifying biodiversity losses due to human consumption: A global-scale footprint analysis. Environmental Science & Technology, 51(6), 3298–3306. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.6b05296.