Definition

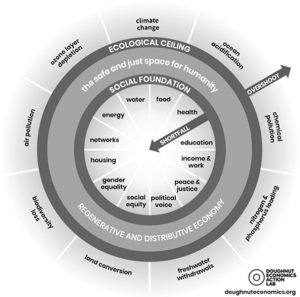

The Doughnut Economy is a conceptual framing best described as a “safe and just living space for humanity” (see Figure 45.1), where the needs of all humanity are met within the physical boundaries of the planet. It combines social justice issues with environmental concerns.

The “sweet spot” is between the inner circle, which depicts the social foundation of human well-being that no one should fall below, and the outer circle, which represents the ecological ceiling of planetary pressure that humanity should not go beyond. Above the social foundation, peoples’ needs for life’s essentials, such as food, water, healthcare, housing, gender equality, and political voice are met. The ecological ceiling represents planetary boundaries, such as climate change, land conversion, and biodiversity loss, which should not be transgressed for the Earth to remain in a stable state within which humanity can thrive. This is part of a group of concepts that define the upper and lower boundaries for consumption and economic activity levels that provide the essential quality of life for humans in the present, while not degrading it for future generations and nature (see also Consumption Corridors, Fair Consumption Space).

Doughnut Economics aims to design a regenerative and distributive economy: an economy that is more equitable and that creates a net positive impact on the environment and society. It puts social and environmental principles at the center of policymaking, thus leading to an economy where the social foundation is met without overshooting the planetary boundaries. Doughnut Economics was first introduced by Kate Raworth. In her seminal 2017 book, Raworth posits that moving toward the Doughnut requires seven major economic transformations, including three fundamental shifts in conceptualizing the economy: (i) change the understanding of the goal of the economy, from chasing GDP growth to living within the Doughnut; (ii) recognize that the economy depends on society and the living world, rather than treating it as self-contained; and (ii) relinquish the baseless belief that economic growth, as measured by GDP, will eventually reduce social inequalities, and instead design a deliberately redistributive system. Doughnut Economics is growth-agnostic: while it advocates a move away from the myopic pursuit of economic growth, it does not take a position regarding the green growth/degrowth/post-growth debates. Instead, Doughnut Economics foregrounds the material (and social) corridor within which human consumption needs to take place. It calls for a shift away from high mass consumption and the narrow view of humans as consumers rather than citizens (see Consumer-Citizen).

History

Doughnut Economics originates from Kate Raworth’s work at Oxfam, a non-governmental organization (NGO) dedicated to alleviating global poverty. In her 2012 Oxfam Discussion Paper titled “A Safe and Just Operating Space for Humanity”, Raworth introduces the Doughnut framework as a new model of prosperity.

Source: Doughnut Economics Action Lab

Doughnut Economics builds on long-standing efforts and concepts of sustainable development, integrating the work of human rights advocates who champion every person’s right to life’s essentials with that of ecological economists who stress the importance of situating the economy within environmental limits. Related complementary concepts include, for example, the Well-being Economy, Foundational Economy, Fair Consumption Space, Consumption Corridors, and 1.5-Degree Lifestyles.

The social foundation of this framework was initially based on United Nations discussions leading up to the Rio+20 conference in 2012. During these discussions, governments identified 11 social priorities to be achieved over the next decade, focusing on enhancing well-being, productivity, and empowerment. The 12 dimensions in the 2015 UN Sustainable Development Goals are now used as the social foundation.

The ecological ceiling of Doughnut Economics is based on the concept of planetary boundaries, established by 28 Earth system scientists in 2009. This concept proposes thresholds for nine critical Earth system processes, which, if exceeded, could lead to irreversible and, in some cases, abrupt environmental change, moving Earth out of a stable state. Led by the Stockholm Resilience Centre, the planetary boundaries framework has been revised multiple times since its inception, with the latest update in 2024 quantifying all boundaries and concluding that six of the nine have already been breached.

Raworth followed up on the 2012 discussion brief with a 2017 book titled Doughnut Economics: Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st-Century Economist that further explored the economic thinking required to bring humanity into the Doughnut. These seven principles are shown in Figure 45.2.

Different Perspectives

The Doughnut Economics framework has sparked various critiques, with the question of growth proving particularly contentious. Advocates of growth-based development challenge its proposed economic rethinking, relying on familiar arguments in favor of competition, market efficiency, and technological progress. In contrast, critics of growth as a societal priority argue that the agnostic position of Doughnut Economics’ thinking fails to address the destructive aspects of GDP and allows for continued growth rather than promoting genuinely alternative development pathways (see Degrowth). Empirical studies on the implementation of the tools and concepts of Doughnut Economics suggest that growth, indeed, often reasserts itself – not unlike findings in related approaches like the Well-being Economy or Circular Economy. As a result, some critics frame Doughnut Economics as “watered down” and easily instrumentalized for “business as usual”.

Such criticisms often overlook what proponents perceive as a key advantage of Doughnut Economics compared to more radical approaches: it has successfully prompted engagement by various actors and communities (see the Applications section) including institutional actors integrating the Doughnut framework into formal structures. Empirical evidence suggests that the model’s clear communicability and ideological flexibility are central to its success. Raworth herself acknowledges ties to more radical approaches such as Degrowth, stating, “It’s not the intellectual position I have a problem with. It’s the name”. The model’s “growth agnostic” stance may, therefore, be seen as a strategic choice, enabling it to gain traction without being dismissed immediately by established stakeholder groups.

However, these critiques highlight an important gap in the approach’s consideration of power dynamics, politics, and instrumentalization. Doughnut Economics’ “go-where-the-energy-is” attitude tends to avoid directly confronting incumbent actors and institutions and instead focus on successes rather than shortcomings. While telling alternative stories of economic thriving is crucial, it is equally important to consider those who remain disadvantaged, despite – or even because of – initiatives inspired by Doughnut Economics (see Climate Justice).

Application

Initially designed with a global perspective, the Doughnut Economics framework has been adapted for national and subnational applications, exploring its potential to drive meaningful change at various levels. To support the practical application of the framework, the Doughnut Economics Action Lab (DEAL) was established in 2019. Launched as a Community Interest Company in 2020, DEAL aims to move from the ideas of the Doughnut framework to transformative action. The platform provides tools and resources for collecting locally relevant, data-led targets and indicators to create a “Portrait” of a place with local aspirations and global responsibilities for the social foundation and ecological ceiling.

A challenge that arises when scaling down the planetary boundaries for local applications is that the baseline remains global, and calculating national or local shares requires the application of a distributional mechanism. It could be the case that improving access to basic resources and services in some areas would increase the pressure on, and potentially contribute to breaching, the ecological ceiling. This would have to be addressed through extensive redistribution and reduction of consumption and pressures through, for example, technological and institutional innovations, to ensure that minimum needs are met for all (see Sufficiency).

Source: Doughnut Economics Action Lab

DEAL also collates stories of application of the framework in different communities globally. Applications include engagement, communication, awareness raising, education, data-led evaluations of progress, and supporting local authority policy, planning, and decision-making (see examples in Box 45.1). The aims, outputs, and outcomes of applications vary according to the lead organization (e.g., local authority, community hub, education, or action group), resources and funding, data availability, and participation.

While the various applications of the Doughnut framework testify to its value as an analytical tool and a visual framework for communication, awareness-raising, and decision-making, its use encounters several challenges. These include general obstacles faced by transformative approaches, such as siloed decision-making, lack of higher-level political support, and difficulties in navigating power dynamics, inequalities, and trade-offs (see Political Economy of Consumerism). Furthermore, the downscaling of the model often comes along with a lack of data or indicators on regional and local levels and needs to acknowledge the specificities of place. Academic studies have focused on resolving technical and data-related issues and several practitioner-led approaches have been developed.

Box 45.1. Examples of applications of Doughnut Economics

Community groups

Numerous Dommunity groups, community hubs, and action organizations have explored the Doughnut framework for their locality, by creating what the DEAL calls a “Community Portrait of a Place” using participatory workshop approaches. This aims to provide a holistic picture with diverse inputs and perspectives that can be a starting point for action. A Community Portrait of a Place can be completed alongside a Data Portrait of a Place, which aims to build a quantifiable picture of a place in the Doughnut. Examples listed include a neighborhood in Birmingham (UK), Minato ward in Tokyo (Japan), and Bielsko-Biała (Poland).

Policy, planning, and decision-making

Several cities and regions are applying Doughnut Economics in planning and policymaking including Amsterdam, Melbourne, and the Brussels City Region. The most prominent example is Amsterdam, which was the first municipality to develop a “City Portrait”: similar to a Community Portrait, this methodology downscales the Doughnut from global to city level. Other examples include the German municipality Bad Nauheim, which has launched a comprehensive public engagement initiative aimed at integrating Doughnut Economics principles at the local level. The Swedish municipality Tomelilla is using the Doughnut model for building a new school (Schmid, 2024).

Education

According to the DEAL website, children and young people understand Doughnut Economics faster than most adults. DEAL provides activities and lesson plans. Youth activities have been carried out in countries such as Greece, Slovakia, and the Netherlands.

Business

DEAL launched a tool for businesses to engage with Doughnut Economics in 2022. It provides guidance on how businesses can transform their “deep design”, focusing on a company’s purpose, networks, governance, ownership, and finance (see The Role of Business, Sustainable Finance). The aim is that following this, companies will be empowered to pursue strategies, practices, and business models to help move toward the Doughnut.

Further Reading

Doughnut Economics Action Lab. (n.d.). Available at: https://doughnuteconomics.org/ (accessed: 20 August 2024).

Fanning, A.L., O’Neill, D.W., Hickel, J., & Roux, N. (2022). The social shortfall and ecological overshoot of nations. Nature Sustainability, 5(1), 26–36. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-021-00799-z.

Raworth, K. (2017). Doughnut economics: Seven ways to think like a 21st-century economist. Chelsea Green Publishing.

Savini, F. (2024). Post-growth, degrowth, the doughnut, and circular economy: A short guide for policymakers. Journal of City Climate Policy and Economy, 2(2), 113–123. https://doi.org/10.3138/jccpe-2023-0004.

Schmid, B. (2024). The spectre of growth in urban transformations: Insights from two Doughnut-oriented municipalities on the negotiation of local development pathways. Urban Studies. https://doi.org/10.1177/00420980241305322.