Definition

Eco-communities are grassroots movements for social and ecological change. They are self-organized initiatives, independent of government control, that develop practices, infrastructure, and spaces to live more sustainably and in harmony with each other and the environment (see Grassroots Innovation, Alternative Consumer Cooperatives). Eco-communities are collectively organized housing, livelihood, and educational spaces purposefully designed to regenerate ecological and social environments from resource depletion and inequality. Eco-communities bring together residents with a collaborative spirit to build a better future. They seek (i) to self-provide, as far as practically possible, their own energy requirements, food, livelihoods from the land or locally, and resources for building their homes, and (ii) to minimize waste generation. The social dimensions of eco-communities are just as vital as their ecological features. Eco-communities practice participatory self-governance, share common resources, have systems of sharing between residents, and have expertise in non-violent communication and conflict resolution (see Sharing Economy).

History

Cattaneo (2014) first used the term eco-communities to reference human communities that shared an intent to reconfigure their environmental impact in how they lived and worked in their everyday lives. This coalesced the commonalities between ecovillages, intentional communities, ecological co-housing, and low-impact developments. What began as back-to-the-land experiments and ecological intentional communities in the 1960s and 1970s evolved into ecovillages such as Auroville (India, 1968), The Farm (USA, 1971), Damanhur (Italy, 1975), SEKEM (Egypt, 1977), Findhorn (Scotland, built late 1980’s), Huehuecoyotl (Mexico, 1982), Gaia Association (Argentina, 1991), Dyssekilde (Denmark, early 1990s), and Sieben Linden (Germany, 1997). These communities interconnected informally but were not part of an international movement until the formation of the Global Ecovillage Network in 1991.

Historically, eco-communities have thrived in rural settings due to ample space, privacy, freedom, and affordable land. However, there’s a growing trend of urban ecovillages. Pioneering examples include Freetown Christiania in Copenhagen (founded in 1971) and UfaFabrik in Berlin (founded in 1979). This shift toward urban locations reflects a desire to influence sustainable urban development and gain greater political influence due to their proximity to city centers. This evolution encouraged the inclusion of residential co-housing, the design and density of which suited smaller urban spaces (see Urban Planning and Spatial Allocation). There has also been a move away from manual-labor-intensive land-based income, which some struggled to sustain as they aged. Recent examples of these urban experiments include LILAC in England (see Figure 69.1), the Kailash ecovillage and Los Angeles Ecovillage in the United States, and Cascade CoHousing and Christie Walk in Australia.

Source: Pickerill et al., 2024

Different Perspectives

Eco-communities are experiments in building a more sustainable and equitable world. They, however, vary significantly in size, social and economic structures, residents’ composition, ecological impact, and how they relate to space and their neighbors. Eco-communities share a collaborative spirit, innovative approach, environmental focus, and purpose. They are about building and living overlapping lives, finding ways to exist together, and mutually supporting each other through collaboration and shared living. This means residents work together, share resources, and make decisions collectively. Eco-communities are also spaces of experiments and innovation. Eco-communities act as laboratories for new social and environmental solutions (see Living Labs). They explore alternative economic models and ecofriendly practices. Given this experimental approach, it is not surprising that eco-communities are also dynamic, in constant flux, messy spaces of doing, making, and creating. Eco-communities are unfinished projects, adapting to new circumstances and needs. Reducing environmental impact is a core principle. People living in Dancing Rabbit Ecovillage (Missouri, USA), for example, use significantly fewer resources (less than 10%) per person than the average American across most categories (Boyer, 2016). This is achieved through shared resources, local production, and sustainable living.

While many eco-communities might not articulate themselves as explicitly anti-capitalist, the majority start from a quest to remove themselves from capitalist extractive systems and seek economic alternatives to traditional capitalism (see Well-being Economy, Degrowth, Ecological Economics, Foundational Economy). They promote local livelihoods, minimize consumption, and explore non-monetary systems (see Sufficiency). This reflects a desire for a more sustainable and equitable economic model.

Eco-communities, while offering a promising future, face several hurdles. The very idea of community can be divisive. Eco-communities often seek a specific kind of community, geographically close-knit with shared values. Community can be a powerful political project of togetherness, but it can also be exclusionary and limit participation. A significant critique of eco-communities is their apparent homogeneity. They tend to attract a narrow demographic, often white, educated, and well-off. This lack of diversity limits the applicability of their innovations and can make them unwelcoming to outsiders. The focus on shared identity can also lead to a homogenous aesthetic across eco-communities globally. In other words, an eco-community kitchen in Thailand (Panya Project) looks much the same as one in Spain (La Ecoaldea del Minchal). Such homogeneity is not only potentially off-putting to newcomers but also suggests that eco-community ideas are replicated across the globe without necessarily emerging as distinctively place-based projects that adequately reflect local specificities. Equally, eco-community living is demanding. The romanticized view of a simple life overlooks the realities of collective decision-making and manual labor. Reaching consensus takes time, and the work can be physically challenging. Additionally, some eco-communities rely on volunteers, raising questions about long-term sustainability.

Eco-communities also tend to operate on a small scale, leading some to dismiss them as insignificant. However, many actively share their knowledge and resources beyond their borders, acting as hubs for wider environmental and social activism (see Social Movements). The challenge lies in “scaling out” their positive impact while maintaining the core values that make them successful. Finally, as eco-communities become more popular, their radical ideals might weaken. Some communities adopt more individualistic and market-oriented practices to survive financially. Additionally, many rely on younger residents for manual labor, raising questions about how they will adapt to an aging population. These challenges highlight the need for eco-communities to find ways to be more inclusive, adaptable, and resilient while staying true to their core principles.

Application

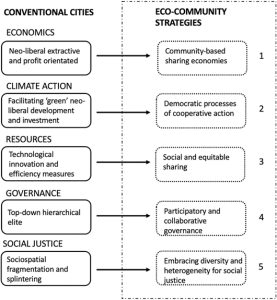

Many of the practices, infrastructures, and designs eco-communities have developed can foster more sustainable places to live where everyone benefits. This is best demonstrated in tackling the problems of intensive resource use and pollution in cities. Current solutions, often focused on green development and technology, are dominated by corporations, and exacerbate social inequalities. An approach is needed that fosters ecologically sustainable and equitable cities for the future, and eco-communities offer five strategies (see Figure 69.2).

First, community-based economies: instead of relying on resource extraction, cities can build local economies based on shared resources and collaboration. Second, cooperative action: decision-making shouldn’t be top-down. Democratic processes and cooperation will empower communities to find solutions together. Third, social resource management: cities can prioritize social approaches to managing resources, ensuring everyone’s needs are met sustainably. Fourth, participatory governance: collaborative governance allows residents to contribute directly to urban planning and policies, promoting equity and fairness. Finally, embracing diversity: cities thrive on heterogeneity. Recognizing and celebrating social differences is crucial for building a just and sustainable future. By exploring these strategies and their real-world applications, we can equip cities with the tools they need to become models of sustainability. This will pave the way for more sustainable places where all residents can enjoy benefits.

Source: Pickerill et al., 2024

Further Reading

Boyer, R.H.W. (2016). Achieving one-planet living through transitions in social practice: A case study of Dancing Rabbit Ecovillage. Sustainability: Science, Practice and Policy, 12(1), 47–59. https://doi.org/10.1080/15487733.2016.11908153.

Cattaneo, C. (2014). Eco-communities. In G. D’Alisa, F. Demaria, & G. Kallis (Eds.), Degrowth: A vocabulary for a new era, pp. 165–168. Routledge.

Christian, D.L. (2003). Creating a life together: Practical tools to grow ecovillages and intentional communities. New Society Publishers.

Pickerill, J., Chitewere, T., Cornea, N., Lockyer, J., Macrorie, R., Malý Blažek, J., & Nelson, A. (2024). Urban ecological futures: Five eco-community strategies for more sustainable and equitable cities. International Journal for Urban and Regional Research, 48(1), 161–176. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.13209.

Sanford, A.W. (2019). Living sustainably: What intentional communities can teach us about democracy, simplicity, and nonviolence. University Press of Kentucky.