Definition

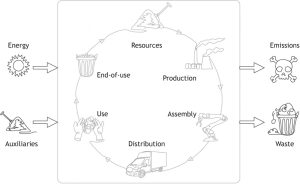

Ecodesign is an integral part of the design process, used to minimize the environmental impact of a product throughout its entire life cycle. The life cycle of a product is the complete path that a product takes, from raw material extraction to end of use. For each phase, inputs (auxiliary materials and energy) and outputs (waste and emissions) need to be considered and minimized (Figure 81.1). Overall, the designer seeks an optimal compromise between all of the product aspects (ecological, technical, human-centered, economical), as the environmental impact will always exist. There is no such thing as a one-fits-all solution, with each case having its own optimal solution.

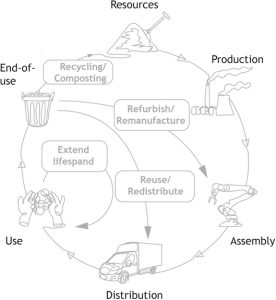

Ecodesign facilitates the main principles of the circular economy by slowing down, narrowing, and closing resource loops (see Circular Economy and Society). During the design process, the principles such as reuse, repair, refurbishment, and recycling are taken into account (Figure 81.2). Ecodesign also supports the implementation of new circular business models such as product-as-a-service (see Product-Service Systems).

We identify three key aspects of ecodesign:

- The first aspect is thinking in functionality, not materiality. The designer starts from the functional fulfillment of the product. Why design an improved shampoo bottle, for instance, when a block of soap has the same functionality, without the need for packaging and transport of water? In the same context, we see the emerging model of product-as-a-service. Many people need mobility, not a car. Any vehicle that is owned and maintained by the manufacturer will be designed and used in a different manner than one that is sold to the customer.

- The second key aspect is life cycle thinking. The example in Box 81.1 explains this approach.

- The third key aspect is value chain cooperation. Cooperation in the entire economic system is essential to the transition to a sustainable society (see Role of Business in Sustainable Consumption). This means cooperation between existing and new partners, between colleagues and competitors, and so on. The designer should interact with all involved parties and facilitate their contribution to sustainability.

Box 81.1 Life cycle thinking as an approach to ecodesign

Let us take the simplified choice between a steel and an aluminum car bumper, looking at ecological impact:

The steel bumper is heavier, but overall it requires less energy (and thus emissions) than the aluminum version, due to the high energy inputs required in aluminum production. It is also cheaper in production. From a production point-of-view, the steel version is therefore the best ecological choice.

However, in the use phase, the weight of the bumper has a large impact on fuel efficiency and carbon emissions. When all the calculations are done, aluminum emerges as the optimal ecological choice.

History

Approaches to dealing with environmental issues inherently differ from country to country, and from continent to continent. The Western world plays a significant role in both the problem and the solution because of its early industrialization and policy impacts.

The emergence of the grassroots environmental movement in the 1960s brought environmental awareness to the masses (see Social Movements, Grassroots Innovation). In the 1970s, in response to the oil crisis, the focus was mainly on reducing energy consumption. In the early 1980s, the discovery of hazardous waste dumps directed attention to waste management, largely by incineration. Guided by the principle of “cradle-to-grave”, end-of-pipe techniques made their appearance to comply with government regulations seeking to reduce air emissions and other discharges to the environment. Overall, the focus was on harm reduction and process-orientation, not product-orientation.

Source: By authors

In the 1990s, attention shifted upstream to product-integrated environmental care. The terms “ecodesign”, “Design for Environment”, “environmentally friendly design”, “ecoefficiency”, and others were given more and more substance. In the beginning, ecodesign was mainly focused on designing products made from waste, bio-based materials, or the development of non-fossil-energy-consuming products such as electrical products based on solar panels. In the 2000s, the ecodesign-based approach became increasingly formalized and standardized, supported by the popularization of the cradle-to-cradle concept. The European Ecodesign Directives and the European Green Deal, as well as the elaboration of the circular economy model by the Ellen MacArthur Foundation and others, gave a major boost to the wide adoption of ecodesign.

Different perspectives

Ecodesign is not a specific extra layer in the design process, but an integral part of it. It is sometimes misused as the “green sauce” on top of the product, with many such examples emerging in packaging (see Greenwashing). Some replace single-use recyclable plastic packaging with complex paper-based non-recyclable packaging. Elsewhere, we regularly see the claim of plastic-free packaging, while it is made from bio-based plastic. Ecodesign efforts alone cannot guarantee sustainability; other stakeholders should adapt as well, including consumers in their behavior and decision-making by policymakers (see Behavior Change, Co-Benefits of Climate Policy). There are many incorrect interpretations and confusion regarding the ecodesign approach. In Box 81.32, we illustrate the most important such misconceptions.

Box 81.2 Common misconceptions about the ecodesign approach

Misconception: Ecodesign ensures sustainability.

Correction: Ecodesign only focuses on the ecological aspect of sustainability. Of course, social and economic issues relevant to sustainability are also taken into account during the design process, but these are not the main targets of ecodesign.

Misperception: Ecodesign is mainly for energy-consuming or energy-producing products.

Correction: Ecodesign applies to all kinds of products in all different sectors: consumables, consumer goods, or capital goods.

Misperception: Ecodesign and circularity are synonyms.

Correction: Design for circularity is part of ecodesign. Design for circularity focuses on closing the loop, while Ecodesign also focuses on the environmental impact of each step of the life cycle of the product (input energy and materials and output of waste and emissions.

Misperception Ecodesign means selecting ecological materials.

Correction: Ecodesign is more than material selection. The ecological impact of a product is defined by much more than the material alone. Aspects like physical connections, business models, product architecture, looks, etc. are all part of ecodesign as well (see The Role of Business). Furthermore, the environmental impact of a material is often only evaluated for the production phase. The material choice has consequences for all life cycle phases, so should be evaluated accordingly (e.g., see Box 81.1).

Misperception: Ecodesign is making products from bio-based materials.

Correction: Bio-based materials are often portrayed as the holy grail in sustainable product design. Some definitely have sustainable potential, but bio-based materials also have environmental issues. No fundamentally ecological material exists; every material has its impact. It is all about the sustainable use of materials.

Misperception: Ecodesign and circularity are mostly focused on the recyclability of the materials.

Correction: Ecodesign supports prolonging the use phase of the product. Recycling has its limits and comes at a price, both economically and ecologically. Also, there may be an important difference between theory and practice (see Attitude-Behavior Gap).

Misperception: The environmental impact and circularity can be fully calculated.

Correction: The environmental impact and circularity cannot be narrowed down to a quantitative figure. Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) studies incorporate life cycle thinking but remain based on many estimations, assumptions, and general data. Also, inherently different types of impacts are matched through weighting factors. In the end, the LCA results have a big uncertainty range and can be manipulated. This does not mean that the designer should not use quantitative numbers at all to evaluate impacts but be aware of complex comparisons. Either way, the designers should use qualitative methods, which are based on ecodesign guidelines (Design for X guidelines).

| Product name | Product type | Design for X | Intervention |

|---|---|---|---|

| Slimbox | Packaging machine & software | Logistics | Made-to-measure cardboard packaging to reduce packaging waste production and CO2e emissions while optimizing costs |

| Frame.work | Modular laptop | Longevity | Laptop with replaceable and upgradeable parts architecture, allowing for longer use |

| Juunoo | Room separator walls | Disassembly | Interior wall system that can be disassembled and reassembled so reuse is possible |

| The New Raw | 3D-printed furniture | Recycling | 3D-printed large objects made from recycled plastic, also in mono-material |

| Atlas Copco Reman | Compressors & generators | Remanufacturing | Business model where they remanufacture compressors and generators, reducing the need for new resources |

| Bounty Select-a-size | Paper towels | Sustainable behavior | Additional perforations let the user choose exactly the amount (s)he needs |

| Signify Light as a Service | Corporate lighting | Energy Efficiency | The vendor provides and maintains energy-efficient lights, and optimizes the lighting scheme |

| Fjallraven Greenland Wax | Wax for outdoor clothing | Maintenance | This company sells materials for the care and maintenance of clothes, so they last longer |

Application

The practical implementation of ecodesign is based on the use of guidelines, often portrayed as “Design for X”-guidelines. X stands for the different design strategies, such as “Design for Disassembly”, “Design for Repair”, etc. These are usually connected to one or more life cycle phases. Some examples are presented in Table 81.1.

The main challenge in ecodesign is to find a compromise between the minimization of the environmental impact and the other product requirements. For instance, optimizing energy use may induce a larger use of critical materials (see Rebound Effect, Energy Overshoot, Stocks Versus Flows) or may weaken the functionality of the product. Proper ecodesign finds the right balance. As this is always context-dependent, we must stress that there is no universal ecological solution or material. There is always some form of impact. Ecodesign limits this impact and enables the transition to the circular economy, as stated in the EU Green Deal and the Ecodesign for Sustainable Products Regulation.

Further Reading

Bakker, C., & Den Hollander, M. (2014). Products that last: Product design for circular business models. Amsterdam: BIS Publishers.

Braungart, M., & McDonough, W. (2002). Cradle to cradle: Remaking the way we make things. New York: Search Knowledge.

Circular design: Open source list of book recommendations. (2024). Available at: https://www.circulardesign.it/publications/ (accessed: 8 January 2025).

Ellen MacArthur Foundation. (2024). Available at: www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org (accessed: 8 January 2025).

Van Doorsselaer, K., & Koopmans, R.J. (2020). Ecodesign: A life cycle approach for a sustainable future. Munich: Hanser.