Definition

Ecolabels are informational tools that indicate the environmental performance of a product or service. Manufacturers use ecolabels to communicate environmental information to other businesses and consumers. Ecolabels are usually based on a voluntary certification, which provides information on the extent to which a product or service meets predefined criteria such as energy efficiency, resource conservation, emissions reduction, and waste minimization. The aim is to reduce the information asymmetry between manufacturers (who know a lot) and consumers (who know relatively little) about the environmental impact of a product so that consumers can make more environmentally friendly choices (Noblet & Teisl, 2015). There are different types of ecolabels, depending on the specific scope (from a wide range of criteria to a single criterion) and the type of certifying institution (from third-party governmental labels to self-certified labels by companies).

History

In the 1960s and 1970s, public concern about sustainable consumption and production patterns grew (e.g., through the publication of the Club of Rome’s Limits to Growth in 1972). Originally, ecolabeling schemes were intended as an alternative to government regulations, to enable consumers to make more sustainable choices and reduce the market share of products with poor environmental performance. In 1978, the world’s first government ecolabel was introduced as an environmental protection measure in Germany: the so-called Blue Angel. The environmental label started with six product groups, including CFC-free spray cans, quiet lawnmowers, and reusable bottles.

In Agenda 21, participants in the UN Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro (1992) described environmental labeling as an important instrument for promoting sustainable consumption and production by making it easier for consumers to buy resource-efficient and environmentally friendly products. Since then, ecolabels have proliferated. In 1992, for example, the European Commission decided to introduce the EU Ecolabel for the entire European market. At the same time, however, criticism of the actual effectiveness of ecolabels in reducing the environmental and social impact of consumption has steadily increased. According to the Ecolabel Index (2024), there are currently 456 ecolabels informing consumers from 199 countries about products and services in 25 sectors, such as fashion, tourism, and food. Figure 78.1 shows these milestones in the history of ecolabeling.

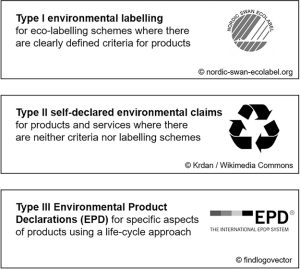

The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) provides standards to ensure the reliability and credibility of environmental claims and declarations. It distinguishes between three types of environmental labels (see Figure 78.2). Type I labels are verified by a third party, that is, an independent organization evaluates and certifies a product’s environmental claims (e.g., Nordic Swan Ecolabel). Type II labels set standards for self-declared environmental claims that do not require third-party verification (e.g., recycling label). These green claims are made directly by manufacturers or producers and are often scrutinized by consumer protection bodies for their potential to mislead consumers. Type III, on the other hand, is mainly a standard for the reporting of environmental data of products between companies (e.g., EPD).

Source: Own illustration, with permission by Club of Rome, Blauer Engel, and Nordic Swan

Source: Own illustration based on International Organization for Standardization. (2019). Environmental labels. Geneva: ISO

Different Perspectives

More recently, the term sustainability label has come into use, referring to labels that focus on the environmental and/or social impact of a product in a broader sense. The effectiveness of sustainability labels varies greatly depending on contextual and personal factors such as age, education, and income. Research suggests that sustainability labels can positively influence consumer behavior and help translate people’s attitudes toward sustainable consumption into actual purchasing behavior, that is, narrowing the attitude-behavior gap. For example, a recent study has shown that compared to positive and negative labels, graded labels (i.e., traffic light labels such as the Nutri-Score in the food sector) are most effective in guiding consumers to make more sustainable product choices (Thøgersen et al., 2024).

With the increasing number and heterogeneity of sustainability labels, criticism of labeling practices has further increased, to the point that they are considered by skeptics as greenwashing. A recurring debate revolves around the reliability and rigor of the criteria for sustainability labels. Critics argue that some labels prioritize marketability over actual environmental or social impact. This problem has been exacerbated by various private companies introducing their own self-declared sustainability labels (i.e., green claims), which often exaggerate the sustainability benefits of products. Concerns about greenwashing underscore the importance of rigorous certification processes, reliable data, and transparent communication to maintain the credibility and integrity of labeling schemes and certification institutions. In general, labeling programs need to be carefully designed to improve transparency, credibility, and accessibility and to increase consumer trust and engagement (Majer et al., 2022).

Another challenge is the proliferation of multiple sustainability labels within the same product category, leading to confusion and skepticism among consumers and hindering informed purchasing decisions (see e.g., Choice Paralysis). Researchers, governments, and companies have begun to consider integrated labeling approaches, which combine multiple environmental dimensions into one overarching meta-sustainability label. This may better address information asymmetry between producers and consumers, reduce information overload, and increase product comparability (Torma & Thøgersen, 2021).

Despite these efforts, sustainability labels often fail to achieve their primary goal of significantly reducing the negative environmental and social impact of consumer goods. One of the unintended consequences of sustainability labels is the rebound effect, whereby environmental impact “savings” from purchasing sustainable products in one domain lead to increased consumption in other domains (see Moral Licensing). Rather than encouraging genuinely sustainable practices, such as not buying products at all, these labels may maintain or exacerbate current unsustainable levels of consumption by inadvertently increasing consumers’ desires or spreading green consumerism.

To overcome these obstacles, some scholars even suggest reversing the logic of sustainability labeling: mandatory non-sustainable labels for less sustainable options (i.e., negative labels, such as those used for tobacco), while sustainable products are given priority and easier market access. This change could better reflect the systemic and complex nature of sustainability challenges and promote strong rather than weak sustainability.

In summary, the potential of sustainability labels in addressing broader systemic issues such as overconsumption and ecological overshoot is limited, as the mere provision of product information is only one of many possible behavior-change interventions (e.g., social comparison, choice editing, incentives). Labeling can only be effective in changing consumer norms and habits in conjunction with government intervention, technological developments, and systemic change promoted by long-term policies (Horne, 2009).

Application

In addition to consumers, there are a variety of stakeholders with different interests in the sustainability labeling landscape. Producers try to gain a competitive edge through certification by balancing costs against the market benefits. In the certification process, they often face the technical challenge of calculating the product-specific environmental (e.g., carbon emissions) and social impacts (e.g., labor conditions) of products with complex or diverse supply chains. Retailers try to influence consumer choice by promoting products with sustainability labels to satisfy demand and improve brand reputation. Business customers and public procurers can prioritize sustainable products and services and set standards for environmental and social responsibility through their purchasing decisions. Policymakers advocate for regulatory frameworks that incentivize the introduction of sustainability labels and encourage market proliferation. Certification organizations strive for credibility by applying strict standards and involving stakeholders to ensure transparency.

Sustainability labeling as an information-based tool to promote sustainable consumption must be subject to political initiatives and regulations to be effective. Important developments in this area (e.g., the EU Green Claims Regulation) aim to combat greenwashing and ensure the integrity and credibility of sustainability labels. Such regulations underline the importance of reliable third-party certification, reliable data, and strict enforcement mechanisms to protect against misleading environmental claims and promote consumer trust.

At the same time, increasing digitalization and big data are enabling new tools (e.g., the European Digital Product Passport [DPP]) to improve transparency, traceability, and disclosure of information along the entire value chain. In addition, the Product Environmental Footprint (PEF) will standardize the measurement of environmental impacts and create a more consistent and transparent basis for sustainability claims in the EU. Such initiatives can provide consumers with comprehensive digital profiles of products, including environmental performance data, supply chain information, and end-of-life considerations. Machine learning models can be conducive to communicating high standards of sustainability in online environments at scale (see Information and Communication Technology). These technical trends may significantly impact the potential and pitfalls of sustainability labeling in the coming decades.

Further Reading

Horne, R.E. (2009). Limits to labels: The role of eco‐labels in the assessment of product sustainability and routes to sustainable consumption. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 33(2), 175–182. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1470-6431.2009.00752.x.

Majer, J.M., Henscher, H., Reuber, P., Fischer-Kreer, D., & Fischer, D. (2022). The effects of visual sustainability labels on consumer perception and behavior: A systematic review of the empirical literature. Sustainable Production and Consumption, 33, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spc.2022.06.012.

Noblet, C.L., & Teisl, M.F. (2015). Eco-labelling as sustainable consumption policy. In L. Reisch & J. Thøgersen (Eds.), Handbook of research on sustainable consumption. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781783471270.00031.

Thøgersen, J., Dessart, F.J., Marandola, G., & Hille, S.L. (2024). Positive, negative, or graded sustainability labelling? Which is most effective at promoting a shift towards more sustainable product choices? Business Strategy and the Environment, 33(7), 6795–6813. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.3838.

Torma, G., & Thøgersen, J. (2021). A systematic literature review on meta sustainability labeling – What do we (not) know? Journal of Cleaner Production, 293, 126194. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.126194.