Definition

Energy consumption arises from almost every human action: the production, distribution, and end-use of goods; the operation of machines and devices; inhabiting buildings with Heating, Ventilation, and Air Conditioning (HVAC) systems; using electrical systems and devices of data storage and retrieval, communication and entertainment; and traveling by different modes of transport. Energy Consumption Behaviour (hereafter ECB) encompasses almost all activities, and historically different approaches have been taken to understanding and addressing it.

ECB is defined as any behavior that involves the consumption of energy. In the context of sustainability, energy consumption typically refers to the use of fuel-based energy, such as electricity or gas, rather than the energy humans expend through physical activities like exercise. This definition is relevant with regard to climate policies that aim to reduce energy use and lower carbon emissions.

History

The term ECB first appeared in the 20th century in studies on energy use across organizations, within sectors or industries, and in buildings. In each area, the insertion of the word “behavior” signaled that studies were about human influences on the consumption of energy, contrasted with purely technical analyses of technological systems and processes, or engineering-focused building research. ECB was not a paradigm of thinking about human action, but a phrase signaling that human behavior introduces “errors” in technical predictions, requiring social science to explain what was happening. The initial social science explanations were dominated by contributions from social psychology. After about 2010, sociological and cultural theories expanded the explanations of human action to include the influences of habit, distinction, social norms, and more (see Moments of Change). In the past decade, there have been attempts to reconcile all these theories about why and how human activity results in energy consumption, some of which are reviewed below.

Different Perspectives

National- and sectoral-level analyses aggregated energy consumption by, for example, industry, agriculture, or transport, and proposed electrification, energy efficiency, and promoting renewable energy generation as the dominant, non-behavioral policy responses. Over the past 30 years, the research and policy focus has shifted to the “domestic” sector, especially household and individual behaviors, which according to one study are responsible for 74% of UK carbon emissions. This level of analysis, associated with carbon footprints, has been criticized as absolving industry and the state from their responsibilities and instead “blaming the victim” (see Household Income Versus Carbon Footprint, Consumer Scapegoatism).

The behaviorist understanding of energy consumption has dominated this way of thinking, seeing ECB as a series of individual, more-or-less rational choices – buying this fridge or that, driving or taking a bus, turning thermostats up or down – largely driven by knowledge about prices, attitudes to the environment, and “utility seeking”. This means that people consciously maximize, for example, comfort, cleanliness, convenience, and speed, while reducing cost. This behavioral understanding of ECB has led to policies aimed at changing Attitudes, Behaviour, and Choices (known as the ABC approach), mostly through price signals or providing more information (see Behavior Change).

Social Practice Theory has redefined ECB by de-emphasizing individual rational choice and emphasizing habit and normalized social practices. The majority of everyday energy consumption is not consciously chosen: we largely do what we did yesterday, or what other people do. This implies that reducing energy consumption is most effectively tackled not through convincing billions of individuals to do things differently but by changing the contexts of those actions, making less energy-consuming ways of everyday life the default or the easiest option (see Choice Editing, Green Nudging). This involves not just changing the devices, vehicles, and infrastructures that “lock-in” higher energy consumption but also addressing social norms: ideally making energy-intensive ways of conducting daily life (e.g., habitual use of air conditioning in homes, offices, and public spaces, use of clothes dryers in households) as socially unacceptable as smoking indoors or drunk driving. Achieving this would require a combination of regulation, infrastructural investments, and supporting alternative ways of living, rather than focusing on persuasion and pricing.

The Needs perspective stresses that ECB is directly related to the satisfaction of basic and universal needs, such as shelter, heat, light, communication, and mobility. However, in highly industrialized societies, this is accomplished in ways that involve the ever-increasing consumption of energy as the satisfiers (technologies) provide more services in socially expected ways, all conditioned by the availability of systems of provision (see Consumption Corridors, Product-Service Systems). As the satisfiers (technologies) used to meet these needs offer more services than are strictly required, they foster overconsumption. A departure from overconsumption to sustainable consumption demands a shift from an efficiency-based approach – which focuses on reducing energy use per unit of service for the same absolute level of service – to sufficiency-based approaches. Adopting sufficiency in ECB includes the reconsideration of which energy services are required and the socially conditioned nature of related activities and practices. Perhaps even more importantly, we should seek to address the dominant interests that structure our ECB through, for example, systems of provision and norm-shaping advertising (see Political Economy of Consumerism). These ratchet up with expectations (of comfort, cleanliness, convenience, and speed) as the technologies that provide them proliferate in more energy-consuming ways.

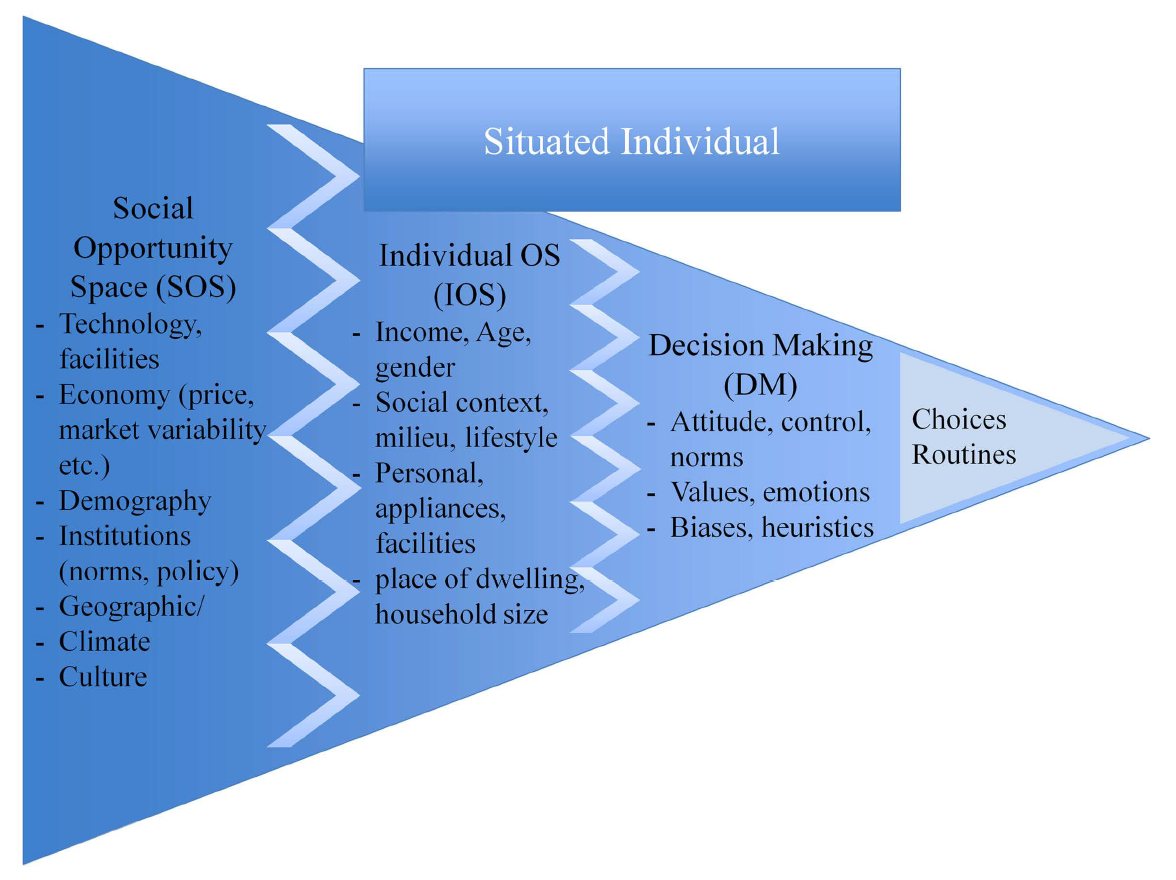

A framework that combines these multidisciplinary understandings is offered by Burger et al. (2015), integrating psychological, economic, consumer behavior, business and political science, and sociological perspectives. Their framework views an individual’s choices and routines as being influenced by decision-making heuristics, and individual and social “opportunity space” features, all of which are influenced by policy structures, policies, and politics (see Figure 10.1).

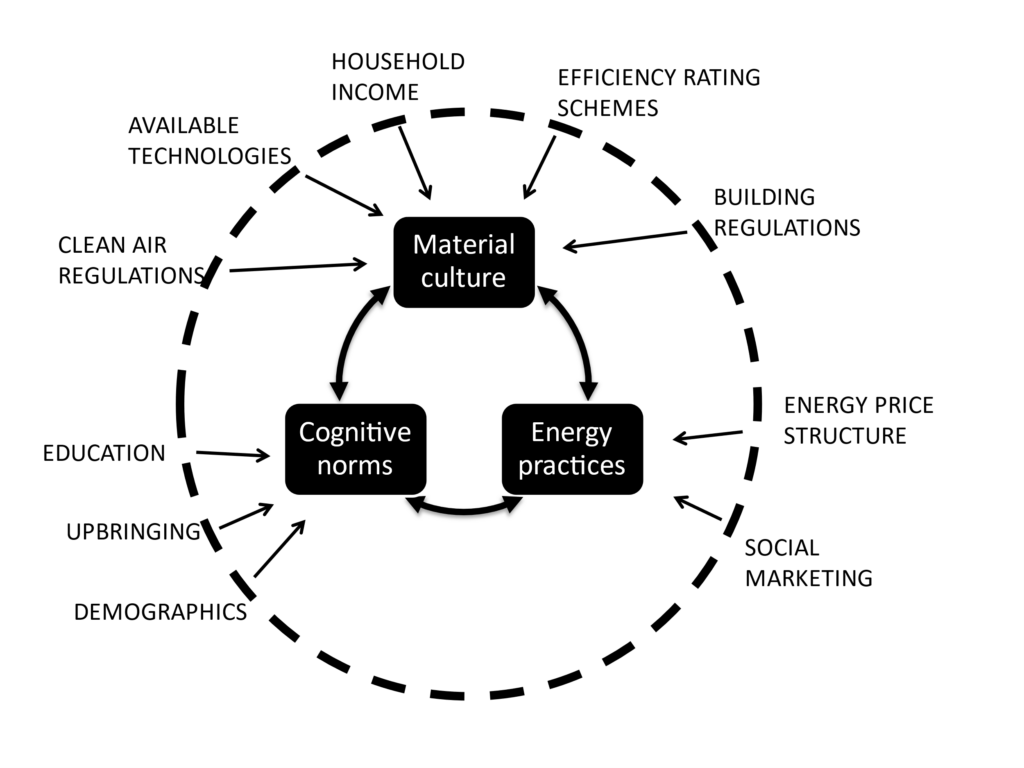

Similarly, Stephenson et al.’s (2010) Energy Cultures framework emphasizes the combined effects of material culture, cognitive norms, and energy practices on ECB (see Figure 10.2).

Source: reproduced from Burger et al. (2015)

Source: Adapted from Stephenson et al. (2010)

Other frameworks emphasize the hierarchy of lifestyle choices (e.g., where to work and live and whether or not to own a car) as setting the choice architecture and thereby determining subsequent day-to-day activity and travel choices. The “orders of need satisfiers” model of Brand-Correa et al. (2020), for example, suggests hierarchical yet interlocking influence from systems of provision (the political economy of technologies and infrastructures) and activities (social practices), which use energy or material services provided by specific technologies to satisfy needs. These frameworks and models shift the focus from individual choices to the larger systems, infrastructures, and social norms that lock in certain behaviors.

Considering the above perspectives about choice hierarchies and decision-makers, it is important to recognize different types of ECB in policymaking. As such, one-shot choices about device, appliance, or even infrastructure purchases may structure subsequent choices and thus require interventions such as incentives for more sustainable options. Repeated choices, such as energy use habits, may be pre-structured or heavily influenced by lifestyle or higher-order choices and require interventions to reshape social norms and choice architecture. Lifestyle or higher-order choices about housing locations, work, transport infrastructures, and how to satisfy basic human needs often require interventions by policies while campaigns could, for instance, make use of moments of change.

Applications

Using the example of a company and its buildings, technical solutions such as smart HVAC might induce passive consumption. Procurement policies based on information and energy labeling could source energy-efficient technologies, low-impact supplies, and/or raw materials. Behavior change policies would attempt to save energy in everyday work processes (e.g., recycling, switching off lights and devices). A key example of a norm-shifting “policy” is “Cool Biz” in Japan, where the Prime Minister and bosses abandoned business suits for short shirt sleeves in hotter weather. This demonstrated changing norms to save energy for cooling.

Domestically, there is a similar focus on heating/cooling individuals rather than spaces, using fans, blankets, and thermals rather than turning up heating or cooling, and the automation of home technologies, for example, to match intermittent renewable energy availability.

Behavior change programs have encouraged “smarter choices”, tending to promote relatively low-effort-low-impact behavior changes such as changing and switching off lightbulbs or lowering thermostat settings. Tackling the more problematic ECB linked to the ubiquitous availability of energy-intensive technologies and the norms of their use remains a key challenge (see Energy Overshoot).

Further Reading

Brand-Correa, L.I., Mattioli, G., Lamb, W.F., & Steinberger, J.K. (2020). Understanding (and tackling) need satisfier escalation. Sustainability: Science, Practice and Policy, 16, 309–325. https://doi.org/10.1080/15487733.2020.1816026.

Burger, P., Bezençon, V., Bornemann, B., Brosch, T., Carabias-Hütter, V., Farsi, M., Hille, S.L., Moser, C., Ramseier, C., & Samuel, R. (2015). Advances in understanding energy consumption behavior and the governance of its change–outline of an integrated framework. Frontiers in Energy Research, 3, 29. https://doi.org/10.3389/fenrg.2015.00029.

Gram-Hanssen, K. (2014). New needs for better understanding of household’s energy consumption–behaviour, lifestyle or practices? Architectural Engineering and Design Management, 10(1–2), 91–107. https://doi.org/10.1080/17452007.2013.837251.

Shove, E. (2010). Beyond the ABC: Climate change policy and theories of social change. Environment and Planning A, 42, 14. https://doi.org/10.1068/a42282.

Stephenson, J., Barton, B., Carrington, G., Gnoth, D., Lawson, R., & Thorsnes, P. (2010). Energy cultures: A framework for understanding energy behaviours. Energy Policy, 38, 6120–6129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2010.05.069.