Definition

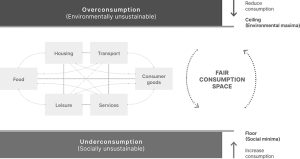

A fair consumption space has been defined as “an ecologically healthy perimeter that supports within it an equitable distribution of resources and opportunities for individuals and societies to fulfill their needs and achieve wellbeing” (Akenji et al., 2021: 13). Recognizing that there are power imbalances in society, especially between rich and poor, and growing competition over resources to meet people’s needs, the approach suggests parameters for ensuring well-being for everyone within ecological limits. Given that household consumption currently drives about two-thirds of greenhouse gas emissions, high importance has been placed on identifying low-carbon lifestyles within an ecologically safe band or area, between an environmental ceiling (or maxima) and a social floor (or minima) (see Figure 31.1). This framework serves to focus on planning and practical decision-making regarding the range of consumption choices that exist across key lifestyle domains such as housing, transport, services, food, leisure, and consumer goods (see Box 31.1).

The approach is based on three key principles:

- Limits: Referring to the need to stay within ecological boundaries and carrying capacity, this principle is implemented, for instance, by developing a carbon or resource budget determined in dialogue with the latest environmental science (see e.g., Personal Carbon Allowance and Ecosocial Contract).

- Equity: This principle ensures that access to resources and opportunities in a climate- and resource-constrained world is fair and enables dignified lives, both now and into the future. This is particularly important given that the worst impacts of ecological devastation are felt by those least responsible for it, often far from where it has been caused (see Climate Justice).

- Well-being: This means that the transformations required to live within the fair consumption space are guided by the well-being of individuals, society, and wider ecologies, rather than other metrics such as economic growth (see e.g., Well-being Economy).

The fair consumption space framework is part of a group of concepts that define the upper and lower boundaries for consumption and economic activity that provide the essential quality of life for humans in the present, while not degrading it for future generations and nature. Consumption Corridors, Doughnut Economics, and Earth System Boundaries are other concepts in that class. The fair consumption space framework particularly ensures that currently vast inequities in environmental impact – resulting from extremes of both overconsumption and underconsumption – are taken into account. Consumption beyond one’s fair consumption space deprives others of their own livelihoods, leading to ecological disequilibrium and social tensions. Given that the emissions of the richest 10% of people account for 36–49% of the global total, while the poorest 50% account for just 7–15%, necessary changes in lifestyles and consumption will differ drastically between social groups (Akenji et al., 2021). There is, for instance, far more scope and necessity for change among those with high-impact lifestyles undertaking frivolous consumption (such as mega-mansions and private yachts and jets).

Source: Akenji et al. (2021)

History

This concept emerged in the wake of decades of unsuccessful attempts to stem ecological impacts through techno-fixes, market-based approaches, and cycles of intergovernmental negotiation. The term itself was first introduced by Lewis Akenji in 2017 at an event organized by the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) examining how ecological and social crises can be jointly addressed. While coming into use in the early 2020s, the approach has a longer historical precedent, being adapted from the idea of “environmental space” developed by ecological economist Hans Opschoor in the late 1980s. Opschoor and colleagues focused primarily on the limits of natural resource use, describing external limits to – and the need to drastically reduce the use of – things like oil, copper, natural gas, and biomass. This work foreshadowed later definitions and ideas identifying a “safe operating space” for humanity emerging in the 2000s, such as the “planetary guardrails”, “planetary boundaries”, and more recently, doughnut economics and consumption corridors.

Different Perspectives

Fair consumption space takes a political economy approach and accounts for power disparities among different actors in society – for example, protecting the need for increased consumption by disadvantaged groups to meet fundamental needs for well-being. A clearly articulated space provides a balance in which wants should not overpower needs, economic demands stay within environmental limits, and political platforms and policies should not exacerbate social disparities and ecological deficits.

The potential of changes in lifestyle and demand has often been underappreciated or overlooked in favor of technological changes or upstream innovations in production. This bias has its roots in skepticism of individualistic consumption shifts, most famously recognized through practices such as taking shorter showers and using paper straws. The fair consumption space challenges the false dichotomy between individual behavior change and system change. Lifestyles are instead understood to include a complex web of topics such as care, voluntary and community work, and social and political activism (see Social Movements, Consumer-Citizen, or Boycott and Buycott). It therefore factors in broader patterns and social practices, which are often intimately related to social systems and societal provisioning (see Social Practice Theory).

A second site of tension is that the focus of the fair consumption space approach to date has largely foregrounded climate change, identifying lower-carbon lifestyles that keep us on track to stay below a 1.5-degree rise in global temperatures. This focus on carbon emissions alone – or what has been called “carbon reductionism” – can exclude a more holistic treatment of challenges like resource exhaustion, habitat destruction, biodiversity loss, and environmental pollution. For this reason, a more holistic environmental footprint or resource-focused approach is sometimes used.

Thirdly, the approach faces uphill struggles in implementation as it constitutes a direct challenge to business-as-usual politics and economics. By explicitly acknowledging resource limits and the need to radically transform social systems for an ecologically constrained future, the idea of a fair consumption space challenges mainstream economic assumptions of infinite economic growth through innovation and resource substitution. The inequities it addresses are likely to provoke political resistance, particularly from elites seeking to protect the most high-impact lifestyles, even if the global majority and most marginalized would instead benefit from more equitable social relations.

Application

Studies have shown vast potential for demand-side climate mitigation, reducing sectoral emissions by 40–80% (Creutzig et al., 2022). A fair consumption space allows global and national targets around more sustainable lifestyles to be formulated, and progress toward them monitored. As currently implemented, it is used to identify what have been called “1.5-degree lifestyles” – that is, lifestyles that are sustainable within the thresholds, which would curb drastic climate change, while providing for a good life for all.

Rather than relying on unproven technologies (such as carbon capture and storage) to avert climate change, three parallel efforts are called for in this approach: reducing high-impact consumption (such as phasing out fossil fuel-powered cars); shifting toward more sustainable options (such as getting people to walk, cycle or take public transport, rather than driving); and improving efficiency through technologies, where appropriate (such as shifting to electric cars where there is no alternative to individual mobility) (see Box 31.1).

Through close empirical analysis of lifestyles in particular countries, the fair consumption space has been applied to identify national-level scenarios and highlight particularly carbon-intensive lifestyle patterns. Bengtsson et al. (2024) apply the approach in Norway, finding that nearly two-thirds of the average lifestyle carbon footprint (LCF) is related to just two lifestyle domains: personal transport (36%) and nutrition (27%). From this, calculations are made to identify high- and medium-impact options that could tackle the most damaging lifestyle patterns.High-impact options in this case are defined as those estimated to achieve reductions of between 500 and 1,200 kgCO2e/capita/year. In the case of Norway, these include:

-

- Diets with less meat, especially red meat (640–1,200 kgCO2e). This is particularly aided by adopting a completely plant-based diet, but shifting to a vegetarian diet also results in substantial reductions (see Protein Shift).

- Reduced international flying by traveling less or shifting to train (750–1,130 kgCO2e).

Climate-smart personal car travel, by switching from fossil fuel-based cars to electric vehicles (560 kgCO2e).

- Reduced purchasing of new consumer goods, together with deep decarbonization of the production system (690 kgCO2e).

These figures are based on the average, and so it is crucial to also look at the particularly high-impact lifestyles undertaken by economic elites and the ultra-wealthy. It is also important to acknowledge, as the authors of Bengtsson et al. (2024) do, that the “focus on lifestyles does not imply that individuals alone can make the necessary changes, simply by shifting their preferences and habits. Our lifestyles are part of the cultures we grow up in and live in. They are to a high degree shaped by social norms and expectations, by the economic system and the incentives it provides, and by the technical infrastructure surrounding us.”

Proponents of the fair consumption space concept have also identified potential in three policy approaches:

- Choice editing: This relates to both editing out harmful consumption options (such as banning short-haul flights where trains could be taken) and editing in more sustainable alternatives (such as increased access and quality of public transport). Key questions remain here, of course, about the democratic legitimacy of choice editing criteria and who does the editing.

- Setting limits: Given that offsetting and market-based approaches have failed, capping emissions will be essential to setting the environmental ceiling. This can happen through forms of rationing, though this is controversial and its implementation must be democratically legitimate (see Freedom of Choice).

- Sufficiency: Rather than seeking unbridled economic growth and consumer lifestyles, a needs orientation is required to focus on what is really needed to live a good life within limits. One form this could take is to develop a social guarantee for Universal Basic Services (UBS), facilitating equitable and sufficient access to necessities like healthcare, transport, housing, childcare, and education.

Further Reading

Akenji, L., Bengtsson, M., Toivio, V., Lettenmeier, M., Fawcett, T., Parag, T., Saheb, Y., Coote, A., Spangenberg, J.H., Capstick, S., Gore, T., Coscierme, L., Wackernagel, M., & Kenner, D. (2021). 1.5-degree lifestyles: Towards a fair consumption space for all. Berlin: Hot or Cool Institute. Available at: https://hotorcool.org/resources/1–5-degree-lifestyles-towards-a-fair-consumption-space-for-all/ (accessed: 8 January 2025).

Bengtsson, M., Latva-Hakuni, E., Toivio, V., & Akenji, L. (2024). Towards a fair consumption space for all: Options for reducing lifestyle emissions in Norway. The Future in Our Hands, Oslo. Available at: https://www.framtiden.no/filer/dokumenter/Rapporter/2024/Online_Lifestyle-Emissions-in-Norway_v2-2.pdf (accessed: 8 January 2024).

Creutzig, F., Niamir, L., Bai, X., Callaghan, M., Cullen, J., Díaz-José, J., Figueroa, M., Grubler, A., Lamb, W.F., Leip, A., Masanet, E., Mata, É., Mattauch, L., Minx, J.C., Mirasgedis, S., Mulugetta, Y., Nugroho, S.B., Pathak, M., Perkins, P., & Ürge-Vorsatz, D. (2022). Demand-side solutions to climate change mitigation consistent with high levels of well-being. Nature Climate Change, 12(1), 36–46. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-021-01219-y.

Opschoor, H. (2010). Sustainable development and a dwindling carbon space. Environmental and Resource Economics, 45(1), 3–23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10640-009-9332-2.

United Nations Environment Programme. (2022). Enabling sustainable lifestyles in a climate emergency. Nairobi: UNEP.