Definition

Gender, distinct from sex, refers to social dimensions of being male or female, encompassing traits, behaviors, and roles deemed typical and/or appropriate for men and women (e.g., long vs. short hair). Although partly rooted in biological differences, they are largely socially constructed and vary across societies and times (Wood & Eagly, 2012). People learn the gendered social norms of their socio-environment during their socialization from parents, peers, and other role models. Typically, they are internalized without active deliberation, which is why they are often erroneously considered “natural”. Because of their pervasiveness and ubiquity in everyday life, gender norms thus significantly influence our identity formation and subsequent self-concept. Consequently, common views of “masculinity” and “femininity” strongly shape our actions, interactions with others, and social (self-)positioning, including consumption patterns and attitudes toward sustainability.

This happens through an internal and an external route. Internally, we regulate our emotions, cognitions, and behaviors to conform to internalized gender norms so that what we feel, think, or do is consistent with our gender identity. Deviations would lead to cognitive dissonance (mental discomfort due to contradictory beliefs and actions), which we typically want to avoid. Externally, these norms affect us via social expectations that others place on us. This enacts gendered emotions, cognitions, and behaviors because not feeling, thinking, or acting in gender-appropriate ways can lead to social sanctions ranging from small cues of disapproval to serious physical or psychological violence.

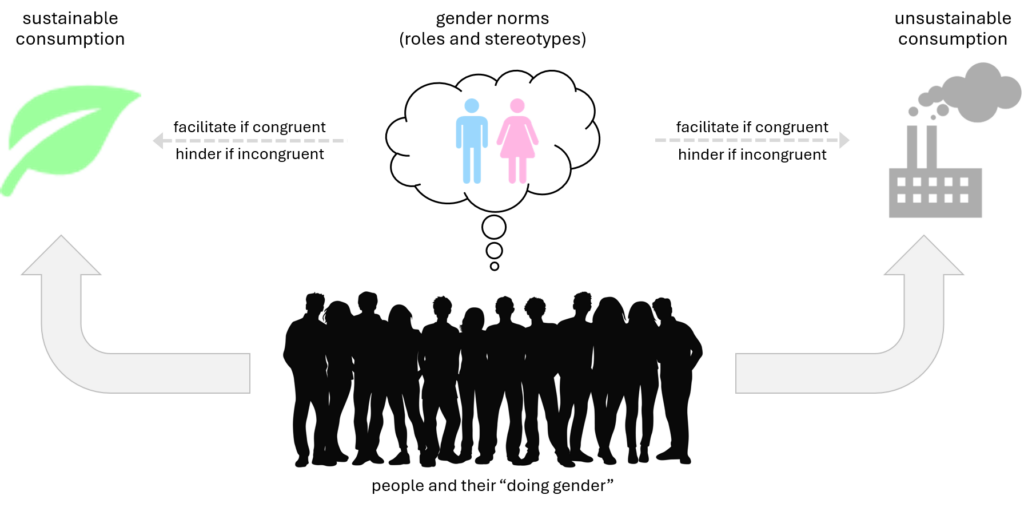

Both pathways operate in parallel, constantly reinforcing and stabilizing each other. Consequently, people continuously reproduce the gender norms of their socio-environment by adhering to them in their daily social practices – a process called doing gender – and simultaneously expecting the same from others; both usually implicitly, without even realizing it (West & Zimmerman, 1987; see Social Practice Theory). In this way, they perpetuate the gendered structure of a society, including the behavioral differences, power dynamics, and hierarchies associated with gender.

In today’s consumerist societies, where acquiring goods and services beyond one’s basic needs plays a central role in people’s lives (see Consumerism), gender also has important implications for sustainable consumption. At the individual level, gender norms can hinder or promote sustainable consumption, depending on how the two are interrelated (Figure 7.1). A contradiction between what’s considered gender-appropriate and what’s required to consume sustainably will create gender-specific barriers to sustainable consumption. The opposite is true, if aspects of sustainable consumption are part of the appropriate “doing gender” for men or women. In this regard, many papers assert that sustainable consumption is more compatible with “femininity”, deterring men from it. However, these studies mostly adopt a so-called weak perspective on sustainable consumption (focused primarily on buying “green” products). Looking at strong sustainable consumption, Wallaschkowski (2023) shows that gender differences in sufficiency depend on the consumption field: Men tend to overconsume “masculine” and women “feminine” products (see Box 7.1 for examples).

Source: By authors

Box 7.1 Examples of gendered barriers to sustainable consumption

Men, meat, and masculinity

In many cultures, there is a strong link between meat consumption and “masculinity”. Meat is seen as a symbol of strength and virility – qualities typically attributed to and expected of men. This association is reinforced by media, advertising, and common narratives, leading many men toward unsustainable and unhealthy meat-heavy diets (see Protein Shift). Conversely, vegetarian men are more likely than women to receive judgmental remarks.

The “female fashionista”

Women’s clothing consumption far exceeds men’s. This can be attributed to the widespread stereotype of the “female fashionista”, associating a fashionable look with “femininity”. Reinforced by the common reduction of women to their appearance, it creates a strong pressure to constantly buy new clothes, which men don’t face with the same intensity (Wallaschkowski, 2023) (see Fast Fashion).

The gendered face of energy poverty

The UN sustainable development goals envision a future with affordable, reliable, and need-adequate access to modern decarbonized energy services for all. However, the persistent gender pay gap and gendered division of care responsibilities leave women more vulnerable to energy poverty. Consequently, they are overrepresented in social housing, where investments in energy efficiency to reduce their energy bill hinge on their landlords or are impeded by their limited financial capacity (Feenstra et al., 2024).

The linkage between sustainable consumption policy and gender-responsiveness at the systemic level can be demonstrated in the energy transition. Given that energy access, consumption, and services are gendered globally, the transition toward 100% renewables requires attention to prevailing gender differences and gender relations to be just and successful. In many countries in the Global South, for instance, women cook on biomass, causing more women to die from indoor air pollution than from malaria and AIDS. However, clean-cooking programs entail high up-front investments and challenge long-standing food traditions. It is, thus, necessary to ensure social acceptance and financial feasibility for these women to avoid detrimental consequences and stimulate the consumption of clean energy for cooking.

History

Historically, “sex” and “gender” were seen as the same thing, with people being categorized as male or female based on biological differences – assuming that anatomy determines social roles and identity. In the mid-20th century, however, psychologists, sociologists, and feminist writers began distinguishing “sex” (biological attributes) from “gender” (roles, behaviors, and identities), arguing that many differences between men and women, which often served as the ideological basis for paternalistic suppression, are socially constructed rather than biologically determined. They pushed for greater equality and questioned prevailing gender roles, paving the way for more diverse gender expressions and “queer” identities beyond the traditional binary, seeking gender diversity and justice. Nevertheless, the traditional separation between “masculine” and “feminine” traits, behaviors, and roles still heavily shapes today’s social reality.

Today, social scientists point to the heterogeneity also within gender groups, recognizing that human diversity entails many characteristics (e.g., gender, age, education, ethnicity, socio-cultural background, (dis)ability, etc.), which combined constitute complex multidimensional identities. Behaviors like energy consumption are influenced by belonging to several groups simultaneously that together determine one’s self-concept and social positioning. The concept of “intersectionality” is therefore increasingly used to amplify when people’s multifaceted identity is overlooked or ignored in data collected, analyzed, and reported to inform sustainable consumption strategies and policies.

Different Perspectives

The importance of gender influencing sustainable consumption can be approached from three different perspectives (Weller, 2017), which correspond to the various dimensions in which gender norms and/or their consequences can be observed.

- Dimension of gender differences: This approach examines differences between men and women in sustainable consumption behaviors. Such studies have revealed, for example, that women are more likely to consider ecolabels when selecting products (see Ecolabeling). Others have compared average carbon emissions or distinct mobility patterns. Typically, results suggest a higher tendency toward consuming sustainably in women; however, this is usually operationalized in its weak form (Wallaschkowski, 2023).

- Structural dimension: This approach assesses the implications of gender inequalities (e.g., in income, access to resources, distribution of care work, etc.) and power relations for sustainable consumption. However, the interplay of numerous intersecting characteristics is too often overlooked. Differentiating consumers beyond the gender binary enables policies that respond more specifically to individual needs and behaviors (Feenstra et al., 2024).

- Symbolic dimension: This approach explores how common notions of “masculinity” and “femininity” regarding sustainable consumption are socially constructed. What traits, behaviors, and roles are ascribed to men and women, and how do they relate to consuming (un-)sustainably? How are these gender norms formed and maintained in our daily social practices? How are they reinforced and perpetuated by (social-)media? How do they foster or hinder sustainable consumption?

Applications

Applying a gender lens in designing sustainable consumption policies is essential to ensure their effectiveness and widespread adoption. First, this requires sufficiently disaggregated data regarding consumption differences between genders (or more complex intersectional identities). We propose five foci for data collection and analysis: physiological, economic, health, socio-structural, and socio-cultural (see Box 7.2).

Box 7.2 Proposed foci for gender-disaggregated data

Five foci for gender-disaggregated data collection and analysis in the example of energy consumption (see also Energy Consumption Behavior):

- Physiological: Women are more sensitive to ambient temperature than men, increasing their energy demand for heating and cooling; however, very young or old age significantly reduces the ability of both to cope with heat or cold stress.

- Economic: Women with low incomes are disproportionately found as heads of households, either as single-parent families or, due to their greater longevity, living alone at pensionable age. This exposes them to a higher risk of energy poverty.

- Health: Living in inadequately heated or cooled homes has gender-specific detrimental implications on respiratory and cardiovascular systems, and mental health and well-being.

- Socio-structural: Energy consumption patterns depend on factors like marital and employment status, which differ between but also among genders.

- Socio-cultural: Stereotypical ascriptions make men, for example, prefer more fuel-hungry cars.

Second, it is important to get an in-depth understanding of the structural and symbolic basis for these differences by gathering both quantitative and qualitative data. Otherwise, there is a risk of their unintentional reproduction and reinforcement. For instance, hiding the ecofriendliness of male-targeted products – to not threaten customers’ “masculinity” – feeds the “green feminine stereotype” underneath this problem. A better option would be marketing communication that deconstructs the notion of green products as “unmanly”. This relates to our third point: Marketers, policymakers, activists, etc., should always scrutinize the gendered implications of their measures. If done right, both can go hand in hand: promoting sustainable consumption and a diverse and just society.

Further Reading

Feenstra, M., Laryea, C., & Stojilovska, A. (2024). Gender impact of the rising costs of living and the energy crisis. Study requested by the FEMM Committee of the European Parliament, PE 754.488. Available at: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2024/754488/IPOL_STU(2024)754488_EN.pdf (accessed: 15 January 2025).

Wallaschkowski, S. (2023). Gender differences in (un-)sustainable clothing consumption. Implications for fostering strong sustainable consumption. Paper presented at the joint 5th International Conference of the Sustainable Consumption Research and Action Initiative (SCORAI) and 21st European Roundtable on Sustainable Consumption and Production (ERSCP), Wageningen University and Research, July 5–8, Wageningen, Netherlands.

Weller, I. (2017). Gender dimensions of sustainable consumption. In S. MacGregor (Ed.), Handbook of gender and environment, pp. 331–344. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315886572.

West, C., & Zimmerman, D.H. (1987). Doing gender. Gender & Society, 1(2), 125–151. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891243287001002002.

Wood, W., & Eagly, A.H. (2012). Biosocial construction of sex differences and similarities in behavior. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 46, 55–123. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-394281-4.00002-7.