Definition

Household consumption varies, sometimes vastly, with different generations, shaped by diverse experiences such as economic conditions, technology, and cultural values (Owen & Büchs, 2024). This is particularly evident in China, due to the vast economic and technological developments which have taken place in the past half-century (Hu et al., 2020).

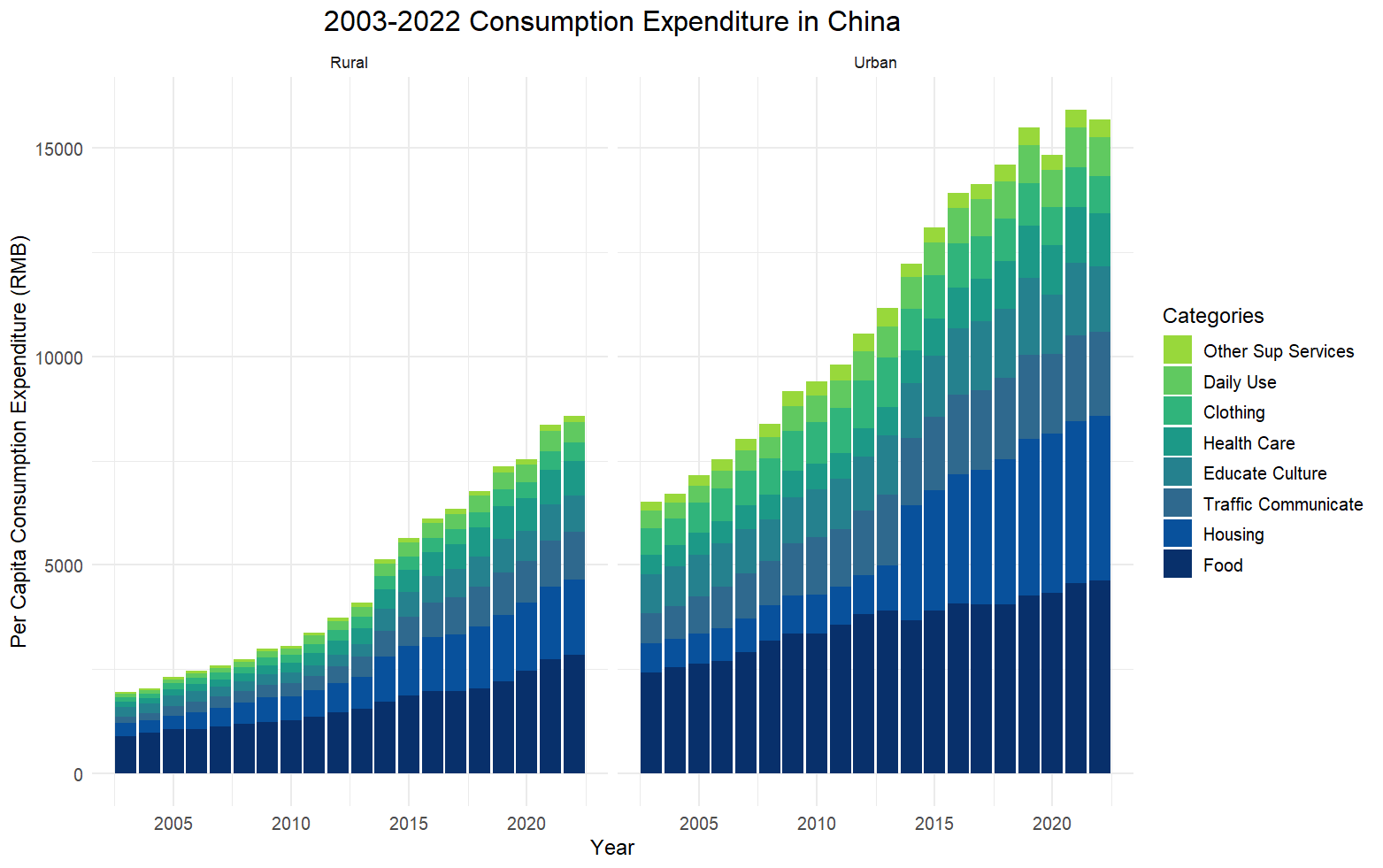

In the 21st century, China’s household consumption expenditures have increased significantly, driven by rapid economic growth. The internet and the rise of social media had a profound impact on consumption patterns and lifestyles, accelerating the shift to mobile payments and making online shopping more convenient (see Information and Communication Technology, Money). As shown in Figure 6.1, between 2003 and 2022 urban household expenditures increased about 2.5 times, and rural household expenditures grew by approximately 4.5 times. However, this also raises concerns about overconsumption and environmental sustainability (Liu et al., 2016).

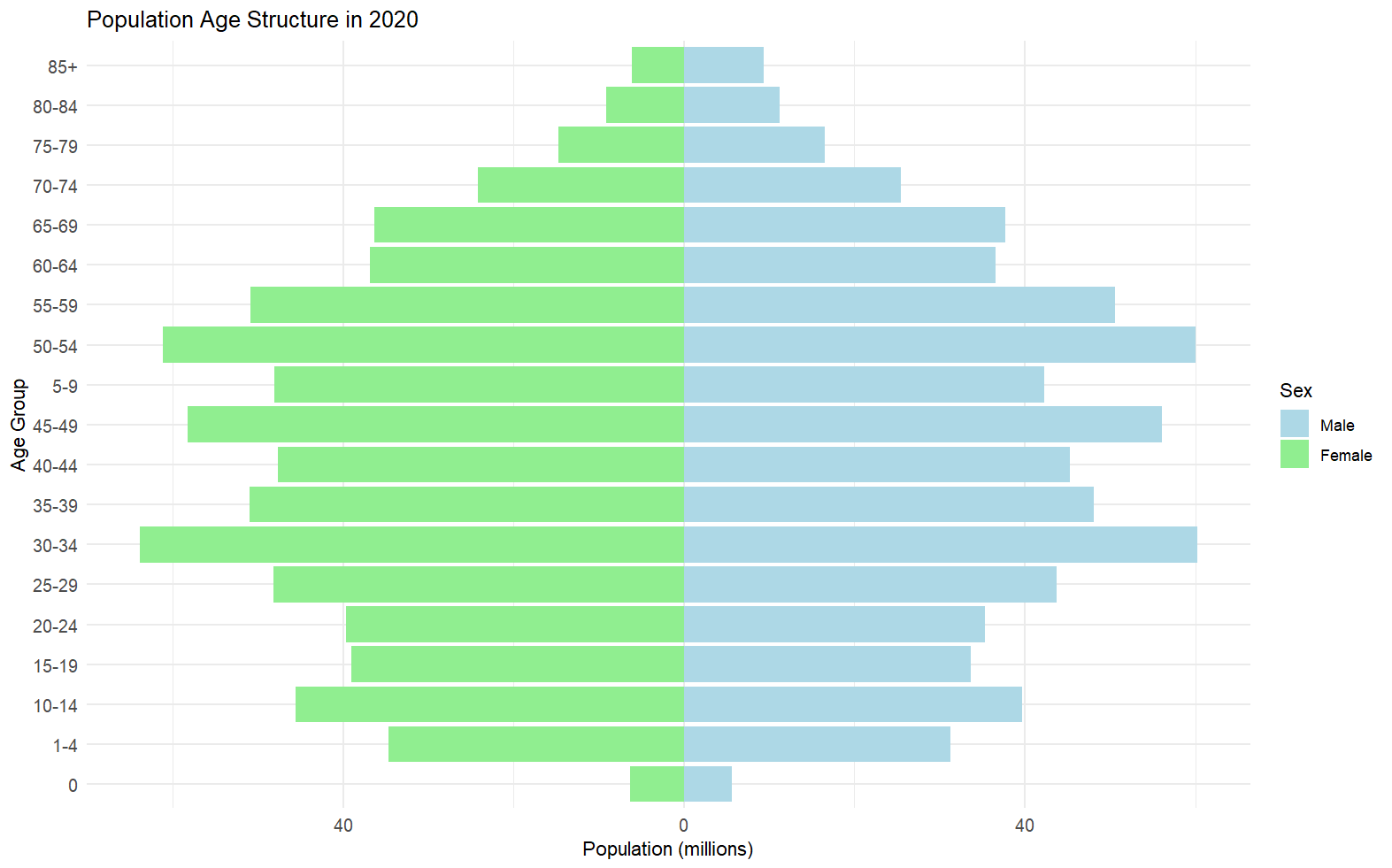

Over the past 70 years, China’s demographic structure was reshaped by rising purchasing power, the one-child policy, and rapid urbanization. The structure shifted from a population pyramid to an “olive” shape, characterized by a substantial middle-aged segment and smaller proportions at the young and old ends, indicative of an aging society (Figure 6.2). Amid this demographic shift and changing family structures, residents’ living habits, consumption behaviors, and social characteristics have changed in generation-specific ways, beyond traditional influences of family status and income. For example, (i) elderly households prioritize health care, medical services, and traditional products, (ii) three-generation households exhibit more diverse consumption patterns, and (iii) the DINK (Double Income, No Kids) families (the number of which has been rapidly growing) spend more on lifestyle and leisure activities.

These evolving demographics and consumption patterns have significant implications for businesses and policymakers aiming to address the diverse needs of China’s population while considering demands for sustainable consumption and lifestyles.

History

Before the 1978 economic reforms, consumption in China was shaped by a planned economy, with the government controlling the distribution and availability of goods. Chinese households prioritized necessities like food, clothing, and shelter, as consumer goods were scarce and personal income limited.

During the Reform Era (1978–1992), China began shifting to a market-oriented economy. Baby Boomers (born in 1946–1964), who were adults during this period, focused on asset accumulation and financial stability (for international comparability, we have chosen to use a familiar categorization of generations such as Baby Boomers, Millennials, Generation X, Y, Z, etc.). Limited resources led to conservative consumption practices, such as relying on coal for energy, maintaining simple diets, and having minimal household appliances. Generation X (born in 1964–1980), coming of age during this era, also practiced resource conservation and prioritized savings, gradually increasing spending on travel, education, and household goods as reforms progressed.

Data Source: China Statistical Yearbook

Data Source: Seventh National Census

Both Baby Boomers and Generation X tend to prioritize practicality and cost over sustainability, often showing a cautious approach to resource use. This generational cohort is typically less receptive to adopting new technologies and sustainable practices due to established habits and skepticism toward new trends. However, their inherent thriftiness aligns very well with sustainable consumption principles (see Quiet Sustainability). For instance, older generations are more likely to repair and reuse household items instead of replacing them and thus reduce waste (see Repair).

The Market Economy Era (1993–2008) brought increased economic liberalization and access to global goods. The rise of e-commerce, including Alibaba’s launch in 1999, began to influence shopping habits. Millennials (born in 1981–1996), who grew up as beneficiaries of the “socialist market economy” and the one-child policy, became China’s first digital-savvy generation. With more disposable income and access to digital platforms, they increasingly purchased luxury goods, global brands, and travel experiences. Generation X adapted to this more open economy and also increased spending on education, health, and imported products while maintaining a level of savings.

The Digital Era (2009 to present) signifies China’s full integration into the global digital economy, heavily shaping the consumption patterns of Generation Z (born in 1997–2012). As digital natives, they engage extensively with online platforms and are inclined toward sustainable and ethical consumption, influenced by both Western trends and domestic regulations promoting ecofriendly products. Millennials, now fully adapted to digital consumption, also emphasize mobile payments, personalized services, and environmental awareness in their consumer behavior.

Both Millennials and Generation Z in China are more open to sustainable practices and new technologies. They are generally more environmentally conscious, influenced by global trends, and have greater exposure to environmental education and the media (Liang et al., 2024). This demographic is more likely to prioritize ecofriendly products, participate in recycling programs, and embrace digital technologies that promote sustainability. For example, younger Chinese consumers are driving the market for electric vehicles (EVs) and renewable energy solutions (see Energy Consumption Behavior, Energy Overshoot, Sustainable Mobility). They are also more inclined to support brands that emphasize sustainability and ethical practices. This generational cohort often leads the way in integrating sustainable practices into their daily lives, from using energy-efficient appliances to participating in community clean-up events.

Different Perspectives

While global labels like “Millennials” and “Baby Boomers” are recognized in China, unique local terms such as “Post-80s” (born in the 1980s), “Post-90s” (born in the 1990s), and “Post-00s” (born in the 2000s) are popular. The Post-80s and Post-90s, often called the “only-child generation” due to the one-child policy, benefit from concentrated family resources but face pressures like supporting aging parents. The Post-80s are generally more cautious, focusing on practical and quality-oriented spending. In contrast, the Post-90s, influenced by Western culture and digital media, embraced diverse consumption patterns, and spending on hobbies and experiences. The Post-00s, fully immersed in digital technology, value self-identity and favor brands that emphasize individuality and social appeal, with a preference for experiential purchases like livestream shopping and influencer recommendations.

Application

Initially, China’s economic growth was driven by policies focused on mass production and exports, transforming the country into a global manufacturing hub. In recent years, the government has shifted its focus toward boosting domestic consumption to create a more resilient economy, less dependent on international markets. The “dual circulation” policy officially emphasizes strengthening the domestic market while remaining engaged in global trade.

Environmental sustainability has recently also become central to China’s policy agenda, with ambitious goals for carbon peaking by 2030 and carbon neutrality by 2060. Although sustainable consumption is primarily promoted by government and academic institutions, public interest is gradually growing. Initiatives like the Carbon Generalized System of Preferences (CGSP), which rewards carbon-reducing actions by individuals and small businesses, encourage low-carbon lifestyles (Chen et al., 2023). Though public awareness is still evolving, these efforts can foster a culture of ecoconscious consumption.

The concept of sustainable consumption is also consistent with China’s traditional culture, where principles from Confucianism and Taoism foster practical, quality-focused purchases and discourage overt displays of wealth (see Conspicuous/Positional Consumption) to maintain collective harmony. Traditional Chinese values such as thrift, family-centered living, and collectivism are often in contrast to the individualism and materialism associated with consumerism. While younger generations are more inclined to embrace consumer culture, there remains an underlying cultural tension between consumerism and Confucian values of moderation and frugality.

Furthermore, economic slowdowns after COVID-19 have dampened consumption, as concerns over job stability, wage growth, and rising living costs make households more cautious with spending. The convergence of strong underlying cultural factors with economic challenges has moderated the expected rise in domestic consumption. This may present a challenge for policymakers aiming to transition from an export-led to a consumption-driven economic growth mode, but it is encouraging from a sustainability perspective.

Further Reading

Chen, F., Chen, Q., Hou, J., & Li, S. (2023). Effects of China’s carbon generalized system of preferences on low-carbon action: A synthetic control analysis based on text mining. Energy Economics, 124, 106867. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eneco.2023.106867.

Hu, Z., Wang, M., Cheng, Z., & Yang, Z. (2020). Impact of marginal and intergenerational effects on carbon emissions from household energy consumption in China. Journal of Cleaner Production, 273, 123022. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.123022.

Liang, J., Li, J., Cao, X., & Zhang, Z. (2024). Generational differences in sustainable consumption behavior among Chinese residents: Implications based on perceptions of sustainable consumption and lifestyle. Sustainability, 16, 3976. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16103976.

Liu, W., Oosterveer, P., & Spaargaren, G. (2016). Promoting sustainable consumption in China: A conceptual framework and research review. Journal of Cleaner Production, Special Volume: Transitions to Sustainable Consumption and Production in Cities, 134, 13–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2015.10.124.

Owen, A., & Büchs, M. (2024). Examining changes in household carbon footprints across generations in the UK using decomposition analysis. Journal of Industrial Ecology, 28(6), 1786–1800. https://doi.org/10.1111/jiec.13567.