Definition

The European Network of Living Labs (https://enoll.org/) currently defines Living Labs as “open innovation ecosystems in real-life environments based on a systematic user co-creation approach that integrates research and innovation activities in communities and/or multi-stakeholder environments, placing citizens and/or end-users at the centre of the innovation process”. Living Labs facilitate interactions between stakeholders to drive innovation and address real-world challenges. As such, they are ideally geared toward innovations that are both locally embedded and potentially scalable. Within them, typically all actors of the quadruple helix – research organizations, policymakers and public actors, business and industry, as well as civil society – come together to work on complex societal challenges by collaboratively developing and testing possible solutions (see Box 24.1). Living Labs generally share the following four characteristics: (1) a transdisciplinary approach to research and knowledge creation; (2) an iterative, experimental design committed to learning and reflexivity; (3) a long-term orientation toward societal transformation and an accompanying interest in transferability or scalability; and (4) a focus on a real-life setting.

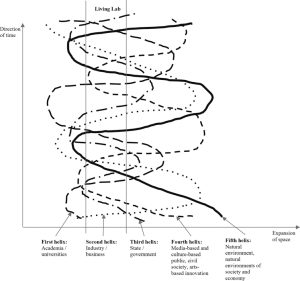

These characteristics can be considered the lowest common denominator across Living Lab research and practice. Notably, they are not explicitly directed at sustainability-oriented change. In view of this omission and in recognition of research on real-world laboratories, especially in the German-speaking research community, we propose to integrate the now widely recognized quintuple helix model in Living Lab research and practice, to ensure an explicit consideration of the environment and society-nature interactions, as shown in Figure 24.1. Thereby, Living Labs can become conducive to the experimental advancement of sustainable consumption and lifestyles.

History

The Living Labs concept originated in the 1990s in the field of technological innovations, specifically in computer-human interaction. William Mitchell at MIT conceptualized them as physical spaces to observe how people interact with technological prototypes in natural or specially equipped settings. Compared to previous (technology) demonstration projects, Living Labs – which soon after also appeared in Europe – primarily focused on user-centered innovation to accelerate application, implementation, and marketization. They also occasionally served as platforms for science communication to showcase high-tech, interconnected, immersive environments.

Living Labs evolved to include experimental approaches to address complex societal challenges concerning housing, mobility, energy, food, or social inequalities. Some focus on specific domains, such as Slovenia’s Green Point Living Lab (https://itc-cluster.com/green-point/), which works on sustainable food system innovations aligned with the EU’s Green New Deal. It consists of Demo Farms for testing real-life agricultural innovations and the Food Supply Living Lab, which focuses on advanced food processing, delivery, and consumption within a regional ecosystem (see Food Miles, Community Supported Agriculture, Food Sovereignty). Other Living Labs follow a cross-sectoral approach, like Ireland’s Dingle Creativity and Innovation Hub (https://dinglehub.com/), aiming to create a sustainable and vibrant community on the Dingle Peninsula – inhabited by 12,000 people and visited by one million annually. This Living Lab aims to foster year-round, well-paid jobs through a diverse ecosystem of stakeholders combining local resources with new opportunities, promoting entrepreneurial growth, and engaging with the community, research, industry, and policymakers.

Source: Authors’ own conceptualization based on Carayannis, E.G., & Campbell, D.F. (2014). Developed democracies versus emerging autocracies: arts, democracy, and innovation in Quadruple Helix innovation systems. Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship, 3(1), 12

These are only some of the Living Labs currently part of ENoLL. Since its foundation in 2006, ENoLL has recognized over 480 Living Labs worldwide as its members and currently has 160 active members.

Different Perspectives

Living Labs relate to and can be found across a broad area of research and action initiatives – from testbeds for technical innovations to grassroots initiatives for social change toward more sustainable ways of living (see Grassroots Innovation, Eco-Communities).

They operate between user-centered design and citizen-led transformation, offering spaces to explore problems and test solutions. However, they risk “solutionism”, where predefined pathways dominate. Three main tensions Living Labs face include: (i) controlled experimentation versus open co-creation; (ii) learning from failure versus showcasing success; and (iii) local embedding versus scalability. With limited, project-based funding, Labs often struggle to preserve participatory processes for deeper local embedding and critical reflection. Building in monitoring, evaluation, and research activities can result in a successful critical reflection that facilitates higher-order learning where the participants collectively reframe the problem and reconsider their own perspectives and assumptions.

The balance between openness and predetermined pursuits depends on who makes decisions, which boundaries are socially constructed and upheld, and which stakeholders, perspectives, and solutions are involved or represented in a Living Lab. This raises issues of innovation management and research policy as well as of participation and democracy. In relation to sustainable consumption and lifestyles, Living Labs may seek to foster sustainable energy prosumption in individual houses, neighborhoods, or entire cities by involving and connecting key actors (see Prosumerism). This can involve top-down governed activities to implement and test technologies like hydrogen infrastructure or bottom-up participatory processes, leaving infrastructural choices to local owners and residents. Even if Living Labs usually aspire to be participatory and democratic, various forms of justice (e.g., procedural, recognition, distributional) should be monitored, and not assumed to be there automatically (see Climate Justice).

Living Labs are able to facilitate higher order and technical learning, including the re-definition of problems and changing interpretive frames; shifts in consumption patterns; governance innovations; and helping communities tackle sustainability challenges. Significant efforts go into evaluating Living Labs, with increasing emphasis on co-evaluation, involving stakeholders throughout the process. ENoLL has been instrumental in formalizing these evaluations, providing frameworks to measure effectiveness, improve methodologies, and enhance the scalability of innovations across regions.

Research on Real-world Labs (RwLs) highlights diverse impacts, categorized into societal and individual changes, governance transformations, and physical modifications. However, an important knowledge gap remains about understanding (i) whether and how a deeply transformative process occurs and (ii) the barriers and enablers for experiments and labs to drive system change.

Living Labs often center on technological innovation. More participatory and pluralist approaches could enhance the social robustness of change, address democratic deficits, and improve sustainability-related outcomes by considering justice, plurality, and equality. Urban Transformation Labs and Thinking Labs exemplify this shift: Thinking Labs foster open deliberation to inform policy and decision-making, while Urban Transformation Labs provide platforms for citizens, businesses, municipalities, and researchers to collaboratively experiment with cross-sectoral transformations.

Application

The concept of Living Labs continues to inspire numerous research programs, projects, and civic initiatives. There have been projects funded by the European Commission (e.g., ENERGISE Living Labs; Box 24.1) that followed a practice-based approach to everyday experimentation, focusing on understanding and reconfiguring the routines and habits that shape consumption. However, these approaches remain sparse and exploratory to date, while most Living Labs focus on changing infrastructures, systems of provision, and regulatory frameworks. The “EU Mission: Soil Deal for Europe, 100 Living Labs and Lighthouse projects by 2030” aims to establish collaborative, real-life experimental spaces where multiple partners, including researchers, farmers, foresters, land managers, and NGOs, co-create innovations for healthy soils at territorial, landscape, or regional scale. Urban sites, smart city initiatives, and societal deliberation are further currently prominent application areas of the concept.

Box 24.1 Practical examples and applications of the concept Living Lab

ENERGISE Living Labs

The ENERGISE Living Labs (https://energise-project.eu/livinglabs) aimed to promote sustainable home energy use by targeting social practices related to heating and washing laundry in eight European countries (see also Energy Consumption Behavior). Each country organized two labs using the same tools and challenges, based on different approaches to participant involvement. That enabled the ENERGISE project team to determine that community involvement outperformed individualistic approaches to stimulating change and that experimentation with everyday practices can lead to lasting, impactful changes.

SmartQuart

SmartQuart (https://smartquart.energy/english-abstract/) is the first Living Lab for the energy transition, funded by the German Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Climate Action, to test innovative technologies under real conditions. The project brings together key stakeholders (public actors, energy providers, users, and researchers) to demonstrate and evaluate energy-optimized neighborhoods for decentralized energy and heating solutions. It aims to provide evidence for the technical and economic feasibility of integrating energy, heating, and mobility sectors within and between neighborhoods. Located in three German cities, the project includes a variety of neighborhood types, from dense urban areas to rural settings, representing typical German communities.

Smart Urban Mobility Meta Lab (SUMMALab)

To facilitate learning between regions and accelerate the scaling of promising solutions, the project is conducted in Amsterdam, The Hague, Delft, and Rotterdam. The focus areas of SUMMALab (https://summalab.nl/) include last-mile solutions like autonomous shuttles, door-to-door options like car-sharing, and changes in urban infrastructures such as parking areas and access restrictions. To support and scale these experiments, SUMMALab develops tools for business models, technical feasibility, upscaling, and mobility and economic impacts, addressing the need for structured development and community involvement.

Urban living labs (ULLs) are multi-actor platforms for co-creation, real-life experiments, and joint learning in cities. They focus on innovating urban practices including governance and planning to address sustainability challenges. ULLs involve diverse local stakeholders and create context-sensitive knowledge, though the scalability of their innovations varies. Examples in the city of Amsterdam include an energy lab, a lab for mixed urban spaces, and two labs for healthy urban environments. The “meta-lab” approach aims to enhance the impact of ULLs by connecting and aligning learning processes across multiple labs.

Smart City Labs are collaborative spaces that integrate advanced technologies to improve (the use of) infrastructure, mobility, energy, and public engagement in cities. Through real-life experimentation and data-driven insights, they seek to foster sustainable urban development, optimize resource management, and enhance the quality of life for residents. An example is the platform smart.aachen (https://smart.aachen.digital/public/en), which connects and supports smart city projects in Aachen, Germany, toward reaching climate neutrality by 2030. These projects include sensors monitoring the water quality in a local pond, a mobility dashboard guiding motorized citizens past traffic to the nearest available parking spot, and the life-saving use of unmanned aerial vehicles in rescue operations.

Thinking Labs are another variation. They are safe spaces for multi- or single-stakeholder groups to exchange ideas about and co-create solutions to specific problems in a facilitated setting. Examples include the European CIMULACT (http://www.cimulact.eu/) and EU 1.5° Lifestyles (https://onepointfivelifestyles.eu/) projects, both of which employed Thinking Labs extensively in multiple countries, also allowing for cross-comparison.

As these and other applications show, Living Labs can facilitate less consumerist lifestyles and community-driven resilience in various ways. By engaging stakeholders in co-creating and testing sustainable systems of provision and practices for localized food systems, minimalism, collaborative consumption, sharing economies, resource conservation, and circular economies, Living Labs can encourage and enable changes that reduce consumption and foster sustainability, especially if an explicit focus on environmental impacts and concerns is maintained throughout the process.

Further Reading

Compagnucci, L., Spigarelli, F., Coelho, J., & Duarte, C. (2021). Living labs and user engagement for innovation and sustainability. Journal of Cleaner Production, 289, 125721. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.125721.

Engels, Franziska, Wentland, A., & Pfotenhauer, Sebastian M. (2019). Testing future societies? Developing a framework for test beds and living labs as instruments of innovation governance. Research Policy, 48 (9), 103826. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2019.103826.

Schäpke, N., Wagner, F., Beecroft, R., Rhodius, R., Laborgne, P., Wanner, M., & Parodi, O. (2024). Impacts of real-world labs in sustainability transformations: Forms of impacts, creation strategies, challenges, and methodological advances. GAIA – Ecological Perspectives for Science and Society. Special Issue, 1–2024. https://doi.org/10.14512/gaia.33.S1.2.

Scholl, C., de Kraker, J., & Dijk, M. (2022). Enhancing the contribution of urban living labs to sustainability transformations: Towards a meta-lab approach. Urban Transformations, 4(1), 7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s42854-022-00038-4.

Vadovics, E., Richter, J.L., Tornow, M., Ozcelik, N., Coscieme, L., Lettenmeier, M., Csiki, E., Domröse, L., Cap, S., Puente, L.L., Belousa, I., & Scherer, L. (2024). Preferences, enablers, and barriers for 1.5°C lifestyle options: Findings from Citizen Thinking Labs in five European Union countries. Sustainability: Science, Practice and Policy, 20(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/15487733.2024.2375806.