Definition

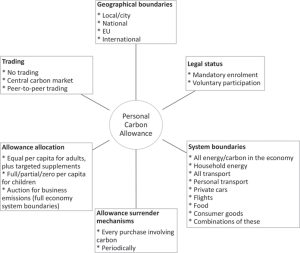

Despite global efforts to decarbonize energy supply, carbon emissions keep rising. Personal carbon allowances (PCAs) is an umbrella term for mitigation policies that aim to limit carbon emissions by allocating a carbon budget to individuals, encouraging them to change their energy consumption patterns, and engaging them in emissions reduction (see Behavior Change and Energy Consumption Behavior). Unlike carbon mitigation policies which tend to focus on energy production, PCA focuses on energy consumers and is sometimes described as a downstream cap-and-trade policy. Several PCA policy designs have been proposed. These vary in their combination of system boundaries, the energy services covered (heating, power, mobility, flights), geographical scale, trading rules, and the allocation and surrender of allowances (Figure 86.1). Fawcett and Parag have shown how different options can be combined to create varied PCA designs including cap and share; tradable consumption quotas; carbon rations; tradable transport carbon permits; personal carbon trading; and individual carbon quotas.

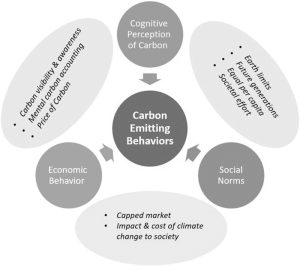

The underlying assumption about how PCA works is that emission reductions would arise through three interconnected mechanisms influencing individual behavior, that is, economic, cognitive, and normative mechanisms (Figure 86.2). In the economic mechanism, the carbon “price” on emissions would incentivize people to choose low-carbon activities and goods. Introducing a virtual “carbon currency” and the scarcity of carbon units resulting from a shrinking cap would also encourage people to mentally account for their carbon usage and promote lower-carbon choices.

In the cognitive mechanism, the carbon cap would spark new conversations about carbon and climate in society. This increased visibility of carbon and heightened awareness of individual impacts on the climate would prompt people to opt for lower-carbon activities.

In the normative mechanism, the underlying principles of PCA – such as environmental limits, fair shares of emissions, societal climate responsibility, and social solidarity – would establish new social norms regarding acceptable behavior, thus encouraging widespread adoption of low-carbon lifestyles.

History

The idea of personal carbon allowances emerged from concepts developed independently in the 1990s by two British researchers, David Fleming and Mayer Hillman. With his economics expertise, David Fleming developed the idea of “domestic tradable energy quotas” as part of an economy-wide mechanism that included carbon auctions for firms. He believed this would reduce carbon emissions more cost-effectively and equitably than carbon taxation. Mayer Hillman, a transport and social policy researcher, was inspired by Aubrey Meyer’s proposal for global “contraction and convergence” of carbon emissions, where nation state emissions per capita first converged and then contracted to stay within safe limits. He was also influenced by Britain’s experience of food rationing in World War II. Hillman called his idea “carbon rations” and saw it as a national route to global contraction and convergence. International researchers developed the central ideas further, with different policy designs emerging.

Source: Authors’ own production, drawing from earlier work – Akenji, L., Bengtsson, M., Toivio, V., Lettenmeier, M., Fawcett, T., Parag, Y., Saheb, Y., Coote, A., Spangenberg, J.H., Capstick, S., Gore, T., Coscieme, L., Wackernagel, M., & Kenner, D. (2021) 1.5 degree lifestyles: Towards a fair consumption space for all. Berlin: Hot or Cool Institute

In 2006, the idea attracted high-level political interest in the United Kingdom, resulting in government-sponsored studies in 2007–2008, including analysis of equity impacts and costs. The UK government department Defra concluded that PCA would be expensive and complex to introduce and was “an idea ahead of its time”. Subsequently, there was limited further official interest in PCA. The only country that has conducted a PCA pre-feasibility study is the United Kingdom.

Different Perspectives

PCA have always engendered divided opinions about its likely effectiveness, cost, fairness, and public acceptability. In part, this is because its impacts depend on the details of policy design and implementation (Figure 86.1). The absence of a detailed or operational PCA scheme creates ambiguity. Disagreements also emerge from competing understandings of fairness, climate justice, mechanisms for change in relation to energy use (Figure 86.2), personal responsibility, and freedom (see Freedom of Choice, Carbon Inequality, Household Income Versus Carbon Footprint, and Consumer Scapegoatism).

Source: Authors’ own production, drawing from earlier work – Akenji, L., Bengtsson, M., Toivio, V., Lettenmeier, M., Fawcett, T., Parag, Y., Saheb, Y., Coote, A., Spangenberg, J.H., Capstick, S., Gore, T., Coscieme, L., Wackernagel, M., & Kenner, D. (2021) 1.5 degree lifestyles: Towards a fair consumption space for all. Berlin: Hot or Cool Institute

Regarding fairness, PCA policies suggest each individual is permitted to generate the same amount of carbon emissions. However, equal carbon emissions do not equate to equal energy use, let alone equal access to energy services. For example, different sources of heating or transportation energy vary in their carbon intensity (emissions per kWh), and renewable energy can be emissions-free – meaning low emissions can result from high energy use and vice versa. Further, an equal per capita emissions allocation does not reflect the variation in people’s energy service needs. Questions raised include how vulnerable households or those with higher energy needs would be treated, what would happen if households ran out of allowances, and the consequences of a particularly cold winter. These questions can only be answered through detailed policy design, which could include allowance for these, and other, circumstances. An implemented PCA policy is likely to look much more complex than the simple principles on which it is based.

Research on public opinion regarding PCA proposals, whether conducted via surveys, interviews, or focus groups, consistently shows that people tend to prefer PCA to alternatives such as a carbon tax. However, they would also prefer that neither PCA nor alternative capping or taxing policies are introduced. Those most positive about PCA value its claims to fairness, and those who like it least have concerns about effectiveness and cost. Without evidence from modeling and research trials, the likely effects of an implemented PCA policy – including its winners and losers, and costs and benefits – will not be understood in sufficient detail for informed public debate.

Application

Piloting a policy with a mandatory carbon cap entails creating a situation in which all citizens within the pilot area have emission caps and allowances are in shortage or surplus – something generally considered impossible. Therefore, trials cannot fully create the conditions that encourage carbon-related behavioral change. The pilots to date have been undertaken voluntarily and were limited in geography and scope.

The most significant PCA research trial was the Australian “Norfolk Island Carbon/Health Evaluation” (NICHE) study, established in 2011; 350 people registered for the trial, which encompassed food, household energy use, and travel, and incorporated a carbon accounting system, rewards for participation, and feedback on emissions. Results showed a switch away from motorized transport (>20% reduction). Participants were more positive about the idea of PCA at the end of the trial than at the beginning.

More recently, the Finnish city of Lahti ran the CitiCAP project (2018–2021), a voluntary incentive system that encouraged users to reduce their mobility emissions via (1) financial incentives through carbon pricing; (2) providing information on users’ emissions and reduction options; and (3) an online marketplace to reward citizens. CitiCAP showed that a PCA for mobility could be implemented with mobile phone technology. The small-scale evaluation indicated self-reported transport emissions reductions by about one-third of users, but with overall rejection of a mandatory mobility PCA.

When the concept of PCA was introduced in the 1990s and gained policy traction in the United Kingdom (from 2006 to 2010), transportation and heating systems – the major sources of direct personal emissions – primarily relied on fossil fuels and carbon-intensive electricity generation. Since then, the electricity system has been decarbonizing and, in many countries (especially Europe and North America), the transition to electric mobility and heating is being supported by dedicated policies (see Energy Overshoot). Given the complexity of introducing PCA, its relevance for the transition to a net zero-carbon economy is open to question.

Most of the current interest in PCA concerns mobility, the sector where energy use is still rising, decarbonization is progressing slowly and individual choices play a major role (see Sustainable Mobility). Various Personal Mobility Carbon Allowance (PMCA) schemes have been proposed, particularly in China. Recent Chinese research includes studies on the design of trading systems, public willingness to participate, explored via choice experiments and other methods, and learning from voluntary personal carbon transport schemes in particular cities. Some PMCA proposals would allow users to trade carbon credits in a market, influencing their travel decisions within set carbon budgets. If combined with good quality, affordable public transport and other low-carbon infrastructure for walking, cycling, and EV charging, PCA might prove a useful addition to the policy mix (see Urban Planning and Spatial Allocation).

Further Reading

Bothner, F. (2021). Personal carbon trading – Lost in the policy primeval soup? Sustainability, 13, 4592.

Bristow, A.L., Wardman, M., Zanni, A.M., & Chintakayala, P.K. (2010). Public acceptability of personal carbon trading and carbon tax. Ecological Economics, 69(9), 1824–1837. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2010.04.021.

City of Lahti. (2022). CitiCAP – Citizens’ cap and trade co-created. Available at: https://www.lahti.fi/en/files/citicap-final-report/ (accessed: 20 December 2024).

DEFRA. (2008). Synthesis report on the findings from Defra’s pre-feasibility study into personal carbon trading. UK Department for Environment Food and Rural Affairs. Available at: www.defra.gov.uk (accessed: 20 December 2024).

Fawcett, T., & Parag, Y. (2010). An introduction to personal carbon trading. Climate Policy, 10, 329–338. https://doi.org/10.3763/cpol.2010.0649.