Definition

The protein shift aims to change how we produce and consume food, away from animal-based proteins (both meat and dairy) and toward proteins from other sources. This shift is motivated by the high negative impacts of livestock production and the consumption of animal-based products on the environment, human health, and animal welfare. Potential alternative sources include plants, insects (where culturally accepted), alternative protein sources like single-cell or microbial protein (microalgae, fungi, protein from fermentation [e.g., mycoprotein]), and cultivated meat. “Protein transition” and “protein diversification” are often synonyms for protein shift.

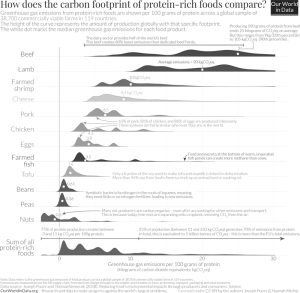

The goal is to meet nutritional needs while staying within ecological boundaries on a global and local level (see Consumption Corridors). On average, plant-based and many alternative protein sources have a lower environmental and climate impact than animal-based products (Figure 75.1) (see Consumption-Based Accounting). Particularly in high-income countries, current food patterns show high levels of animal-based consumption. The consumption of red and processed meat furthermore often exceeds dietary recommendations, negatively affecting human health. Protein intake in these countries is generally sufficient at a population level and even exceeds nutritional needs.

History

The question of eating or not eating meat or dairy has been part of human life for centuries, for reasons of religion, culture, or specific events (e.g., war). After World War II, the consumption of animal-based products in the Western world dramatically increased, primarily driven by the modernization and industrialization of the agricultural sector. This led to increased production and relatively lower prices for all food products. Once a product for special occasions, meat became a commodity available at any time of the day.

For decades, consumption of animal-based products has been a subject of dietary guidelines, almost exclusively motivated by health. Arguably, the FAO report Livestock’s Long Shadow (2006) put the detrimental effect of the livestock sector on the environment in the spotlight for the first time. Since then, growing evidence about the climate and biodiversity crises has led to increased policy attention regarding the relationship between food consumption, especially animal-based food products, and its disproportionate effect on land use change, deforestation, water consumption, and animal waste surpluses. This suggests that food system policies should consider the nutritional requirements of present and future generations and which foods we produce, process, and consume.

Since 2010, the FAO has recommended the development of food-based dietary guidelines (FBDGs) that promote healthy diets and consider the impact of global and local agri-food systems on the environment and human health while being culturally and socio-economically appropriate (see Consumption Corridors). In 2019, the FAO and WHO organized an expert meeting to describe sustainable healthy diets and formulated the Guiding Principles for Sustainable Healthy Diets. Today, other organizations like the IPCC and the World Bank, among others, have recognized that a shift to healthier and sustainable diets, which includes a protein shift, is critical concerning planetary boundaries (see Doughnut Economics) and safeguarding well-being.

Source: Richie, H. (2020) Less meat is nearly always better than sustainable meat, to reduce your carbon footprint. Our World in Data. Available at: https://ourworldindata.org/less-meat-or-sustainable-meat (accessed: 13 June 2025)

Attention to the food security aspects of protein has increased, especially in light of attacks on Ukraine by Russia (beginning in 2022). The European Union (EU) is mainly self-sufficient in agricultural products, but a complex picture emerges when looking at protein. The EU critically depends on imports of plant-based protein like soy or grain, mainly sourced for feed, from Argentina, Brazil, and the United States. The EU livestock sector is particularly vulnerable. This has led lawmakers, academia, industry, and NGOs to call for the EU to develop an EU protein strategy.

Different Perspectives

Although sometimes criticized as a reductionist approach to the challenges surrounding food consumption habits, focusing on protein is necessary due to protein’s status as an essential macronutrient. Protein (and nutrient) rich, animal-based products are, at the same time, a significant contributor to the environmental burdens of food production. Using protein as a lens brings global food system challenges into sharp focus. By promoting the production and consumption of plant-based proteins for human consumption instead of indirect consumption via animals, the protein shift holds enormous potential for planetary, personal, and animal health. There are, however, also resistances to the protein shift (see Box 75.1).

Box 75.1 Special interest pushback on the protein shift

Resistance to the protein shift can be traced to vested interests in sectors that stand to lose out. The 2024 WHO report “Commercial Determinants of Noncommunicable Diseases in the WHO European Region” described obstructions to reducing meat consumption in Europe. Due to increasing market concentration, ten large global meat companies play a defining role in determining how meat and feed are produced, transported, and traded. This enables these companies to exert influence throughout the supply chain and gain political influence. The meat industry engaged in intensive lobbying against key components of the EU’s Farm to Fork strategy, mishandling science and skewing media coverage. These efforts have been successful because proposals put forward as part of the Farm to Fork strategy – such as explicit references to health risks associated with intensive farming, requirements to increase transparency by labeling products, and the ability of EU Member States to impose higher taxes on unsustainable products – have all been delayed or watered down. A proposal to ban the financing of the promotion of red meat was even blocked. In recent years, the EU has invested millions of euros into campaigns promoting beef consumption, including a €4.5 million initiative called Proud of EU beef. The meat industry has also lobbied against initiatives to promote and fund research to develop alternative protein sources. Because of their political power, meat companies have been able to block the development of greener and healthier alternatives.

While the protein shift, as defined here, allows for some animal-based products, some argue that this is only a step toward the ultimate goal of a complete vegetarian (no meat) or vegan (no meat, dairy, eggs, or any animal-based product) lifestyle. Vegetarian and vegan lifestyles do require extra attention to avoid deficiencies in essential nutrients like vitamins (B12, D), minerals (e.g., iron, calcium), and some fatty acids (omega-3), which are less bioavailable in plant-based sources.

The question of which products deserve preference is thus a subject of debate. While it is clear that pulses, nuts, seeds, whole grains, and traditional vegetarian products like tofu, seitan, and tempeh satisfy health and environmental goals, some discussion exists on the risks and benefits of (highly) processed plant-based products. In general, health concerns surrounding ultra-processed food (UPF) consumption are also relevant in the protein shift. On the other hand, these products present an interesting alternative from a behavioral change point of view because they resemble products people are used to regarding look, taste, and preparation. Overall, (highly) processed plant-based products remain under scrutiny.

Application

The protein shift is often recommended qualitatively in food-based dietary guidelines (FBDGs): “Eat more plant-based foods than animal-based foods”. In some cases, the protein shift translates into a concrete target. The EAT-Lancet Commission calculated a healthy reference diet (with a possible range) in grams per day to align with the UN SDGs and Paris Agreement criteria (Table 75.1).

Some organizations or countries propose a target based on the ratio between plant-based and animal-based protein intake. In Flanders, Belgium, the goal is to reach a 60% plant-based protein intake and a 40% animal-based ratio. In the Netherlands, the target is 50:50.

Initiatives like “Meatless Monday” (USA, 2003), “Meat Free Monday” (UK, 2009), and “Donderdag Veggiedag” (Belgium, 2009) aim to educate and incentivize consumers to stop eating meat for one day a week for environmental, animal welfare and health reasons. Campaigns like “VeggieChallenge” (the Netherlands, 2011) and “Veganuary” (UK, 2014) challenge participants to follow a vegetarian or plant-based diet for one month. Other examples are “Semana sin carne” (Spain, 2017) or “Week zonder vlees” (The Netherlands, 2018), which challenge people for a whole week (see Behavior Change).

[TABLE]

The Green Protein Alliance (GPA) was launched in 2016 in the Netherlands by a group of retailers, producers, and NGOs to promote plant-based consumption. Similarly, the Flemish Department of Environment and Spatial Development (Belgium) launched a “Green Deal Protein Shift on our Plates” in 2021, together with more than 80 stakeholders. Singapore took the lead in innovative protein production by making the headlines in 2020 as the first country to take cultivated meat to the market. Meanwhile, a movement pushing universities toward 100% plant-based meals kicked off in the United Kingdom in 2021 and has since spread to other countries. In 2023, Denmark was the first country to publish a national action plan outlining how to transition toward a more plant-based food system (see Box 75.2). Local municipalities and states in the United States are spearheading initiatives in schools, hospitals, and other settings.

Box 75.2 World’s first national action plan for plant-based foods

“Plant-based foods are the future”, the Danish minister for Food, Agriculture and Fisheries wrote in the preface of the “Danish Action Plan for Plant-Based Foods”. “This action plan should inspire everyone who works in our food systems and who influences our daily food choices; from the farmer and food producer to the retailer, the canteen provider, the export markets – and of course the consumer on their daily trip to the supermarket”. This plan puts forward a specific target ratio and couples it with a dedicated Plant-Based Food Grant of roughly 11.26 million euros (84 million DKK) per year from 2023 to 2030. The grant targets innovative projects and has been a big success in terms of interest. In the first round, there were more than three times as many applications than could be granted. Round two resulted in applications worth three times the available budget (which already doubled). This has led the government to increase the budget for 2024–2026 by more than four million euros per year.

While the protein shift is urgent in high-income countries, the need for a sustainable balance between plant-based and animal-based consumption is also evident in middle-income and low-income countries. This is especially the case as demand for animal-based foods will likely increase in these countries as they become more affluent.

Further Reading

Duluins, O., & Barret, P.V. (2024). A systematic review of the definitions, narratives and paths forwards for a protein transition in high-income countries. Nature Food, 5(January), 28–36. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43016-023-00906-7.

Pollicino, D., Blondin, S., & Attwood, S. (2024). The food service playbook for promoting sustainable food choices. Report. World Resources Institute, Washington, DC. https://doi.org/10.46830/wrirpt.22.00151.

Pyett, S., Jenkins, W., van Mierlo, B., Trindade, L.M., Welch, D., & van Zanten, H. (Eds.). (2023). Our future proteins – A diversity in perspectives. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: VU University Press.

Sutton, W.R., Lotsch, A., Prasann, A. (2024). Recipe for a liveable planet – Achieving net zero emissions in the agrifood system. In Agriculture and food series. Washington, DC: World Bank Group.

Willett, W., Rockström, J., Loken, B., Springmann, M., Lang, T., Vermeulen, S., & Murray, C.J.L. (2019). Food in the Anthropocene: The EAT–Lancet Commission on healthy diets from sustainable food systems. The Lancet, 393(10170), 447–492. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31788-4.