Definition

The term “rebound effect” refers to an unintended increase in the demand for energy and/or resources as a result of steps being taken to reduce that demand, for example, through efficiency improvements. The rebound effect can be explained by the following process: Technological progress makes the production process more efficient. Less energy and sometimes also resources are needed to produce the same amount of products and services. However, because of increased efficiency the costs of production decrease, which also can reduce the cost of the final product. A price decrease normally leads to increased consumption of the now-cheaper product or other products. As the demand increases, so does energy consumption and resource use. Thus, some of the energy savings from the efficiency improvement are lost. A rebound effect of (say) 10% means that 10% of the energy efficiency improvement initiated by the technological improvement is offset by increased consumption. Other examples of rebound effects include how building new roads to improve traffic stimulates more car use, or how voluntary reductions in some activity (like traveling) result in increased spending on some other (environmentally harmful) activity. The rebound effect can even backfire, which means that it is larger than the initial efficiency gain, resulting in a net negative efficiency gain.

History

The idea of rebound effects goes back to the suggestion, by economist and philosopher William Stanley Jevons (1865), that improved efficiency of coal-fired steam engines would not result in less but more use of coal and therefore contribute to a more rapid depletion of England’s coal reserves. This became known as the Jevons paradox. The reason for this is that higher efficiency means a lower effective cost of coal, which stimulates the diffusion of coal-using technology throughout the economy.

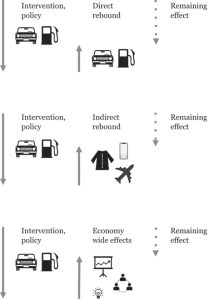

In recent times the rebound effect has been the subject of considerable research. This has deepened our understanding of the dynamics of the rebound effect. Today it is widely acknowledged that there is a direct effect (first-order effect), but also indirect (second-order effects) and economy-wide effects (see Figure 21.1).

The direct rebound effect is caused by increased efficiency leading to lower prices of a product which in turn leads to an increase in demand for the same product. This effect may offset some or all of the savings made from increasing efficiency. A typical example is more fuel-efficient cars which lead to lower fuel costs, but often also lead to the car being driven more often and further (see Moral Licensing).

Source: Malmaeus, M., Nyblom, Å., Mellin, A., Hasselström, L., & Åkerman, J. (2021). Rekyleffekter och utformning av styrmedel (in Swedish). IVL Report B2410

The indirect effect is similarly caused by increased efficiency leading to lower prices, but instead of increasing the demand for the same now-cheaper product, the accrued savings are spent on additional consumption of other products or services. As with the direct effect, the indirect rebound effect may offset some or all of the initial savings.

A rebound effect from technology-based efficiency increases is especially observed when energy is a significant factor in production and when it replaces other factors of production, such as labor. The size of the rebound effect can be partial, and only offset part of the gain; or it can sometimes be total, which means that all the efficiency improvements are offset (Figure 21.2).

The rebound effect has been observed and studied using various metrics. Energy is the most frequently studied, but effects regarding GHG emissions, resource use, and other metrics are also analyzed.

[IMAGE]

Different Perspectives

While the rebound effect from an environmental and resource perspective is a negative side effect, it is a positive effect from a neoliberal economic perspective. The efficiency improvements free up resources that can be used in other parts of the economy and the rebound thus contributes to economic growth.

Some authors even find it likely that a synergistic relationship exists between economic growth and energy consumption, with “each causing the other as part of a positive feedback mechanism” (Sorrell et al., 2009). Researchers have identified the existence of a circular feedback process within which increasing time lags come into play: a quick response (direct rebound), a slow mechanism (indirect rebound), and a long-term restructuring process that affects the overall economic structure (general equilibrium effects). Ayres and Warr (2002) describe resource consumption as both a driver of growth and a consequence of growth and represent the growth mechanism as a positive feedback cycle between consumer demand, industrial investment, declining unit costs, and lower prices for consumers.

Application

Because the rebound effect can be substantial, and even backfire, it is important to include it in the analysis and evaluations of policy (see Co-Benefits of Climate Policy). Without this, the net effects will not be estimated correctly. An example of a policy instrument that takes the rebound effect into account is a cap-and-trade policy. The trade seeks to reduce emissions efficiently while the cap fixes the level of emissions, thus preventing rebound effects within individual businesses or other parties covered by the policy. The cap-and-trade policy does not however prevent system-wide rebound effects. The only way to handle these is through reduced overall consumption and production levels (see Sufficiency).

Further Reading

Allan, G., Gilmartin, M., McGregor, P.G., Swales, J.K., & Turner, K. (2009). Modelling the economy-wide rebound effect. In H. Herring & S. Sorrell (Eds.), Energy efficiency and sustainable consumption. London: Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230583108_4.

Ayres, R., & Warr, B. (2009). Energy efficiency and economic growth: The ‘Rebound Effect’ as driver. In H. Herring & S. Sorrell (Eds.), Energy efficiency and sustainable consumption. London: Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230583108_6.

Jevons, S.W. (1865). The coal question; an inquiry concerning the progress of the nation, and the probable exhaustion of our coalmines. London: Macmillan and Co.

Sorrell, S., Dimitropoulos, J., & Sommerville, M. (2009). Empirical estimates of the direct rebound effect: A review. Energy Policy, 37(4), 1356–1371. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2008.11.026.

van den Bergh, J.C.J.M. (2011). Energy conservation more effective with rebound policy. Environmental and Resource Economics, 48(1), 4358. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10640-010-9396-z.