Definition

Repair entails the fixing of one or several specific malfunctions or performance issues in order to return a product to proper condition or functioning. Issues requiring repair can be cosmetic (e.g., a scratch or dent), functional (e.g., the product does not turn on), or both (e.g., the product’s screen is broken). For every product that is successfully repaired instead of replaced, the need to make a new replacement product is avoided; the substantial waste and environmental impacts associated with material extraction, manufacturing, and transporting the replacement product are avoided. Further, the original product is diverted from becoming waste.

Whereas general repair is undertaken to restore functionality, that is, by fixing or replacing, e.g., a broken chain or handle on a bike, refurbishment (sometimes referred to as restoration) entails the comprehensive work needed to remove and replace worn and/or broken bike parts and tires, for example, as well as to clean the bicycle, perhaps after prolonged storage. Maintenance, on the other hand, involves interventions or fixes that are performed to prevent malfunction or performance issues before they occur, e.g., the cleaning and oiling of the bicycle chain after a ride is completed.

History

For as long as humans have used tools and kept possessions, repair has played an important role in the relationship that we have with material things. In early civilizations, the making and acquiring of possessions required materials and labor that were often limited in supply, and so repair and maintenance played a necessary role in ensuring the care and maintenance of those possessions. The expensive, labor-intensive nature of the products of earlier economies meant that the maintenance and repair of one’s things was a valued investment, and an activity commonly undertaken by those who had the skill to do so.

Mass production and the increasing efficiency of industrialization have enabled increased consumption levels and patterns. As production of goods quickly became more efficient, faster, and cheaper, practices and priorities of frugality and thrift instead became obstacles to the world’s prosperous, growing economies (see Consumerism, Political Economy of Consumerism). In the early 20th century, manufacturers began to explore the intersections of design and product lifetime, including the planned design of product end-of-life (i.e., planned obsolescence), to maintain desired profitability. Over time, these corporate efforts – coupled with marketing narratives focused on “low-prices” and the rise of large-scale retail empires – contributed to a shift in the consumer values driving demand: away from local, high-quality, and long-life products and toward distributed lower-quality, and low-cost, short-life products. The decline of people possessing repair skills and increasing consumption bias in favor of “new” products led to reduced engagement in repair activities in industrialized economies – despite the continued economic necessity and need for repair. In contrast, in emerging and industrializing economies, repair remains generally widely practiced, since repair skills and an economic case for repair and the consumption of repaired products tend to exist in these contexts.

Different Perspectives

Repair is diverse across products and contexts, with perspectives ranging from repair as a technical activity (narrow scope) to repair as a normalized behavior within sustainable economic systems (broad scope). Many discussions (particularly at the policy level) focus on the intentional design of products to make them more repairable (see Ecodesign) and on the provision of repair necessities (e.g., spare parts, tools, schematics, manuals). Some perspectives position repair within an economic system as a relatively more (or less) affordable alternative to buying a replacement when a malfunction occurs. More broadly, repair advocates (e.g., via Right to Repair initiatives) posit repair as an important part of the evolving economic and social norms needed for systems to become more sustainable (see Circular Economy and Society).

Manufacturers are conventionally motivated and incentivized to produce and sell new products. Repair – as an activity that may undermine the sale of new products – is often at odds with conventional linear business models, which generate more profit from selling new than from repair services and, at best, may treat repair as merely necessary for fulfilling warranty commitments. Producers increasingly have the responsibility to internalize the risk and waste associated with their products. Such an Extended Producer Responsibility can be useful for preventing waste in the first place (see also The Role of Business). To counteract the predominant linear business models, calls and action in support of consumers’ “Right to Repair” are growing worldwide (see Box 11.1).

Box 11.1 The right to repair

The Right to Repair is a global social movement that has mobilized to assert the legal right of product owners to have fair access to repair, foremost through demanding access to necessities from producers and repairable product design. Products most commonly included within Right to Repair regulations and policies include personal electronics, automobiles, and farm equipment. In many cases, the Right to Repair movement is as much about demanding government action to clarify and uphold consumer rights (e.g., the right of a product owner to make decisions regarding that product) as it is about holding corporations accountable (e.g., the producer’s responsibility to practice ecodesign).

Application

When a consumer product requires repair, the product user is responsible for deciding whether repair is pursued (or not). This repair-or-not outcome is often influenced by a wide range of conditions outside the control of the individual (Box 11.2).

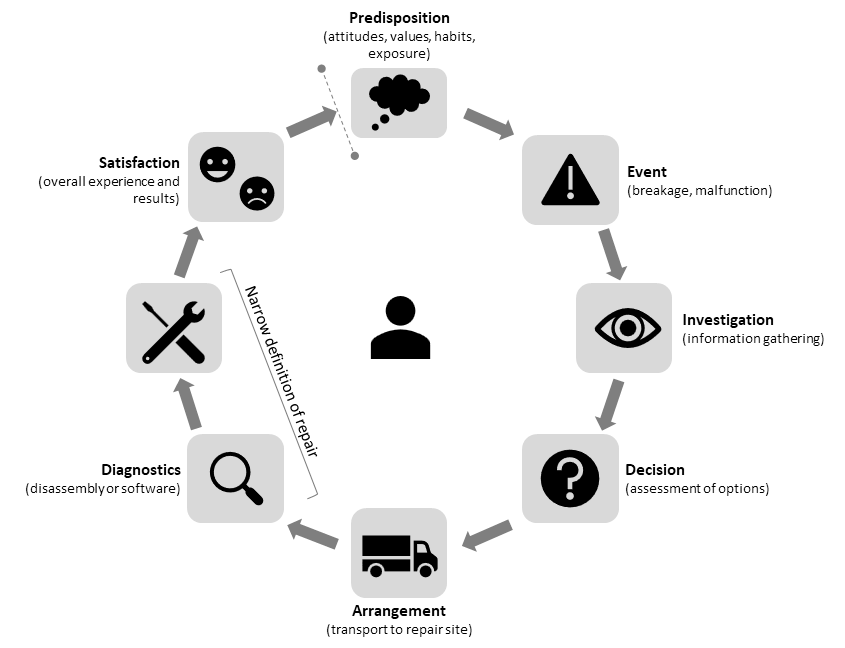

With repair commonly defined narrowly as diagnostics and repair, Figure 11.1 takes a more comprehensive view, depicting repair as a diverse multi-step process. It is rarely as linear as depicted: depending on the outcomes at each stage, it might be necessary to return to previous stages, such as when the “Diagnostics” stage points to an issue that the repairer is unable to fix or the appliance does not fit into a person’s car at the “Arrangement” stage – both requiring a return to the “Investigation” stage to explore other options. Depending on the conditions encountered at each stage (e.g., an individual’s predispositions, the cost of repair, and product design), the repair effort either progresses to the next stage or ceases.

Box 11.2 The elements of repair-or-not

As product designs become more complex (e.g., slim designs and embedded software), the time, labor, and cost required to repair increases. As a result, the economic cost of repair is often surprisingly high, and therefore less attractive to product users when compared with the option for a lower-cost, more easily accessible replacement. Overall, the repair-or-not outcome is determined by a range of conditions encountered in the repair process (Figure 11.1) that can be divided into the following overlapping categories:

- Technical barriers, relating to, e.g., product design and the compatibility and availability of spare parts

- Policy and Legal barriers, relating to, e.g., the constraints imposed on the manufacturing and distribution of spare parts due to intellectual property protection

- Economic barriers, relating to, e.g., the increasing price of a repair relative to the generally decreasing price of a replacement product

- Infrastructural barriers, relating to, e.g., transportation and other accessibility challenges of locating a repair site

- Socio-cultural barriers, relating to, e.g., consumer habits, preference for new versus repaired, and attitudes toward repair as not worthwhile

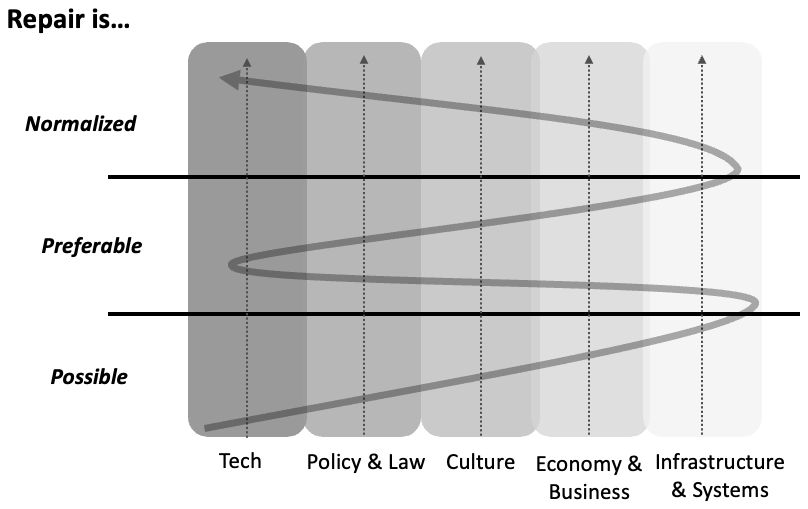

Some key conditions must be in place for the practice of repair to become mainstreamed: first, product repair must be technically possible (e.g., as mandated by the EU’s Ecodesign for Sustainable Products Regulation); second, the repair must be preferable to replacement (e.g., as facilitated via the distribution of monetary repair vouchers in Austria); and third, repair must be normalized (e.g., the realization of a cultural shift toward valuing product longevity and rejecting consumerism). This speaks to a synchronized, gradual change in both the supply and demand of both products and repair across the five elements (Figure 11.2).

The repair of durable consumer products can be conducted in different settings: For a high-value and complex product (e.g., a smartphone or large appliance), a professional repairer may be engaged to perform the repair as a commercial, high-quality activity. In contrast, for other products, individuals may engage in so-called Do-It-Yourself (DIY) and Do-It-Together (DIT) formats of repair. Increasingly common, DIY and DIT non-commercial community repair groups, self-identifying as “repair cafes” and “repair networks”, for instance, offer individuals community-building and the collaborative guidance, tools, and skills needed to engage in successful repair. Accordingly, repair over replacement, as a central principle for sustainable consumption and sufficiency, can lower the cost of living, enhance human and community well-being, and increase material and resource efficiency.

Source: Svensson-Hoglund et al. (2023)

Source: Svensson-Hoglund et al. (2021)

Beyond increased availability and affordability of repair services, many stakeholders who argue for supporting community repair see the normalization of repair and a change toward a more collective “mending mindset” as crucial (see Social Tipping Points). Here, there is potential for repair to be a more radical action in moving toward a more sustainable consumption and production system.

The Right to Repair legislative framework primarily addresses the first level of possibility to upscale repair activities. However, additional measures are needed to reposition repair as a central activity within a sustainable, circular, and sufficient society (Figure 11.2) – via preferability and normalization – which are largely missing from the current focus on a Right to Repair. The shifting of consumer behaviors and attitudes requires, at a minimum, increased public awareness of the benefits of repair and assurance of lower-friction opportunities and incentives to engage in the practice (Figure 11.1).

Further Reading

Bradley, K., & Persson, O. (2022). Community repair in the circular economy: Fixing more than stuff. Local Environment: The International Journal of Justice and Sustainability, 1–17.

Jaeger-Erben, M., Frick, V., & Hipp, T. (2021). Why do users (not) repair their devices? A study of the predictors of repair practices. Journal of Cleaner Production, 286, 125382. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.125382.

Parajuly, K., Green, J., Richter, J., Johnson, M., Rückschloss, J., Peeters, J., Kuehr, R., & Fitzpatrick, C. (2024). Product repair in a circular economy: Exploring public repair behavior from a systems perspective. Journal of Industrial Ecology, 28(1), 74–86. https://doi.org/10.1111/jiec.13451.

Svensson-Hoglund, S., Richter, J.L., Maitre-Ekern, E., Russell, J.D., Pihlajarinne, T., & Dalhammar, C. (2021). Barriers, enablers and market governance: A review of the policy landscape for repair of consumer electronics in the EU and the U.S. Journal of Cleaner Production, 288, 125488. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.125488.

Svensson-Hoglund, S., Russell, J.D., & Richter, J.L. (2023). A process approach to product repair from the perspective of the individual. Circular Economy and Sustainability, 3, 1327–1359. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43615-022-00226-1.