Definition

The sharing economy encompasses a diverse range of practices, activities, and business models where resources are borrowed, lent, shared, bartered, rented, and swapped, often in innovative ways revolutionized by digital technologies (see Information and Communication Technology). The monetized and non-monetized sharing of underutilized products or assets is a common practice within social networks. However, while applications of the sharing economy have become ubiquitous, the term’s definition and the scope of businesses and practices it covers remain contested. Most agree that at its core, the sharing economy is about severing the link between ownership and access and that its novelty (vs. traditional sharing) is in reliance on digital technologies. Beyond that, however, there is much debate regarding what is truly “sharing” and whether a specific activity or business model falls within its scope.

The sharing economy cuts across various domains of consumption and lifestyles, including accommodation, transport, food, skills, spaces, and other goods and services. While there is much overlap between definitions around the sharing economy, there also remain important differences around whether sharing must happen on a temporary basis and in exchange for payment; involve a physical asset; be owned by an individual (also referred to as peer-to-peer sharing); or can also be owned by a company (also referred to as product-service systems or PSS). The positive connotation of “sharing” as a communal activity complicates these boundaries, as many companies (i.e., platforms) are eager to identify themselves as part of the sharing economy and gain the social approval and consumer trust associated with the term. More traditional non-profit actors promoting surplus food exchange, tool libraries, or service barters have also embraced the term (see Grassroots Innovation).

History

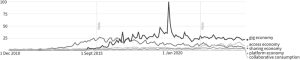

While humans have always shared within circles of families and communities, digital technologies have brought new possibilities around scale and speed (e.g., immediate and global), networks and relationships (e.g., peer-to-peer ratings, stranger sharing), legal frameworks and institutions (e.g., digital cooperatives and commons). The early 2010s were dominated by the so-called idealist discourse, which is perhaps best captured by the term “collaborative consumption” (see Alternative Consumer Cooperatives), see Figure 48.1. The promises of the sharing economy were numerous, and it was assumed that its benefits would be widely shared. Consumers would gain access to goods that they may otherwise be unable to afford. The shared assets would typically be under-utilized, and sharing them would reduce demand for new goods and their production lowering environmental pressures. Workers would earn additional income and enjoy flexible working arrangements on the platforms, which in turn would generate profits. Social networks would expand and people would build relationships around sharing activities.

Source: The authors generated this figure based on Google Trends

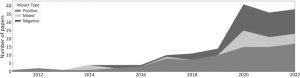

Source: Meshulam et al. (2024)

While proponents of the sharing economy are still plentiful, empirical evidence over the past decade has cooled off the initial enthusiasm, painting a more complex and nuanced picture. The early promises of social and environmental benefits are increasingly put into question in the evolution of the sharing economy. Developments scrutinizing the environmental impacts (Figure 48.2), quality of relationships, and access associated with the sharing economy have been particularly prominent.

Different Perspectives

Environmental Impacts: Shared consumption at the household, neighborhood, or community level holds the potential to reduce environmental impacts; for example, as people share living space, rides to work, or appliances, the provisioning system requires fewer resources per person (see Stocks Versus Flows). Emerging research, however, suggests that such ecoefficiency gains are often eroded when sharing systems scale up. First, supportive logistics operations may increase (e.g., rebalancing bicycle stocks at the end of the day or more deadhead miles on Uber as geographic areas expand). Second, lower costs for sharing economy users, together with added income for providers, may trigger rebound effects leading to an overall increase in demand for products and services. Third, sharing can displace not only high-impact but also low-impact products or services. For example, shared scooters often replace walking and public transport rather than single occupancy car travel (see Sustainable Mobility). Finally, when such sharing economy alternatives become mainstream, economic incentives could change, leading to negative environmental and social spillovers. For example, as Airbnb grew in popularity, the incentives to purchase residential real estate that could serve as full-time Airbnb rentals increased, raising housing costs and lowering overall average occupancy. Critically, the sharing economy under capitalism is characterized by an incentive to scale up to make profits, which limits the potential for environmental benefits.

Social Impacts: The utopian rhetoric of the widely shared social benefits of the sharing economy and the establishment of strong bonds between strangers has also been disputed. Some have praised workers’ freedom and autonomy, particularly those that rely on additional income. However, the sharing economy has also been criticized for its precarious labor conditions, defined by income instability, lack of security, discrimination, and exploitation. Class, race, and gender dynamics dominate for-profit and not-for-profit sharing economy enterprises, and the high prerequisites for participation (e.g., skill, technology, time) act as barriers to securing access to essentials among the most vulnerable. The sharing economy thus tends to reproduce wider inequalities across class, race, gender, and other social characteristics in the distribution of its benefits.

Applications

Today, the digital sharing economy is a $150 billion market where individuals share or gain temporary access to a broad range of assets, from tourist accommodation and transportation to clothing and food. Some of the earliest well-known examples of peer-to-peer sharing platforms include Airbnb and Couchsurfing in accommodation; Uber, Lyft, and Didi in ride-hailing; and Taskrabbit in freelance labor. Centralized ownership sharing (i.e., PSS) includes platforms such as Car2Go, Lime, and Rent the Runway. Yet, while sharing platforms can be found across most consumption domains, including prams (Buggybooker), tool libraries (Tulu), and food sharing (Olio), finding rules of thumb for optimizing the environmental or social benefits of sharing is challenging.

Research suggests that small-scale, local sharing of physical products or assets among peers (e.g., neighborhood sharing of books, seeds, and other items) can have environmental benefits if the potential for added operations (e.g., long-distance travel) is limited. In business-owned sharing, benefits are more likely in the employment of newer, more efficient stocks where use-phase impacts are high, but business models are not reliant on overproduction and overconsumption. Critically, sharing has recently expanded into luxury consumption domains such as yachts and even private flights. In such cases, sharing likely induces demand for services and goods that otherwise would not be consumed.

When considering social benefits, unmonetized peer-to-peer sharing may indeed foster stronger community ties (e.g., Olio, HomeExchange). Yet sharing does not seem to transcend social classes, as individuals tend to share mostly with others of similar socio-economic status and it often requires a degree of cultural or physical capital to participate (e.g., technological literacy and access). In addition, research suggests that social capital is likely a prerequisite for successful sharing.

As research increasingly shows, the sharing economy faces significant barriers to delivering improved environmental outcomes, access to essential goods and resources, and stronger social bonds. Such developments are unlikely to be realized through platforms and environments characterized by inequality, exploitation, commodification, ecological overshoot, and individualism. Promising alternatives have been proposed, including platform cooperatives (e.g., Stocksy) and solidarity networks (e.g., Shareable); policy innovations and partnerships (e.g., co-creating urban commons); and universal, democratic service provisioning (see Universal Basic Services). However, such alternatives would have to directly engage with profound economic, political, and socio-cultural challenges to contribute to a wider socio-ecological transformation.

Further Reading

Ivanova, D., & Buchs, M. (2023). Barriers and enablers around radical sharing. The Lancet Planetary Health, 7(9), E784–E792. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2542-5196(23)00168-7.

Makov, T., Shepon, A., Krones, J., Gupta, C., & Chertow, M. (2020). Social and environmental analysis of food waste abatement via the peer-to-peer sharing economy. Nature Communications, 11(1156). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-14899-5.

Meshulam, T., Goldberg, S., Ivanova, D., & Makov, T. (2024). The sharing economy is not always greener: A review and consolidation of empirical evidence. Environmental Research Letters, 19(013004). https://doi.org/10.1088/1748–9326/ad0f00.

Schor, J.B. (2020). After the gig: How the sharing economy got hijacked and how to win it back. Oakland, CA: University of California Press.

Schor, J.B., & Vallas, S.P. (2021). The sharing economy: Rhetoric and reality. Annual Review of Sociology, 47, 369–389. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-soc-082620–031411.