Definition

The concept of a steady-state economy, as it is currently used, was introduced by Herman Daly. In a steady-state economy, physical quantities of people (world population) and our artifacts are held constant. These artifacts include homes, vehicles, fridges, stoves, factories, power plants, and other consumer and producer goods used by people.

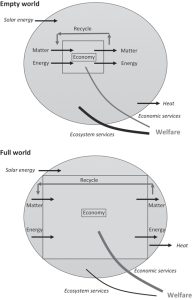

Daly’s idea was to constrain the stocks of population and artifacts to reduce the demands we put on the planet. Humans and our belongings are created using materials and energy and require a continual stream of materials and energy to function. When these stocks are growing, then the flow of energy and materials required to create and sustain them must also grow, leading to resource depletion and exhaustion (see Box 44.1 and Figure 44.1). Growing stocks of people and artifacts also lead to growing levels of waste and pollution that overwhelm Earth’s assimilative capacity, creating problems such as climate change, acid rain, ozone depletion, and the eutrophication of water bodies. (See Figure 44.1 where a growing “full-world” economy takes up much more of the ecological carrying capacity of the planet).

Box 44.1. System dynamics differentiates between stocks and flows

Stocks change over time and are subject to flows. The level of water in a bathtub is a simple stock, subject to the inflows of water from the faucet and outflows of water down the drain. Similarly, the world population is a stock of people that changes subject to the inflows of births and the outflows of deaths. When births outnumber deaths in a given period, the world population increases. When the opposite is true, the world population decreases. If births and deaths are equal, the world population stays “steady”, in dynamic equilibrium, at a given population level. This same kind of dynamic equilibrium can be achieved with stocks of consumer and producer goods if inflows of investment equal outflows of retirement and depreciation (see Stocks Versus Flows).

The stocks of consumer and producer goods that Daly suggests we constrain are not without benefit; they all provide services in our economy. The housing stock provides shelter (see Sustainable Housing). The stock of automobiles, buses, trains, planes, and bicycles offers the service of mobility (see Sustainable Mobility). If we constrain the number of homes and vehicles we produce on Earth, we risk creating a stagnant economy that does not meet the needs of the population.

To avoid this stagnation, Daly suggests we focus on constraining the energy and materials that we use as inputs to create and sustain the stocks. If we constrain our energy and resource inputs, we can still create more efficient stocks that use less energy and materials, and that better meet our needs. This would be a process of qualitative improvement that Daly calls “economic development”. Just like a new recipe can provide culinary delights with the same quantities of ingredients, chef’s labor, and cooking time, economic development would allow a given level of stock and material throughput to generate greater levels of happiness (see Well-being Economy).

Source: Ecological Economics 2nd Edition, by Herman E. Daly and Joshua Farley. Reproduced by permission of Island Press, Washington, DC

In contrast to this vision of sustainable economic development, Daly defines economic growth as a focus on growing the stock of consumer and producer goods, requiring increasing inputs of energy and materials. Bigger stocks might provide more services to humanity, but would also generate ecological costs that undermine our well-being (see Degrowth).

In a steady-state economy, the goal of policymakers should not be to maximize the size of our stocks of goods, but instead to maximize the services we receive from our stocks, and to minimize the throughput needed to maintain and create the stocks.

Sustainable consumption within a steady-state economy would be consumption that uses energy and materials at a rate that can be regenerated without depletion and that generates levels of waste that can be safely absorbed by our environment (see Box 44.2).

Box 44.2. An economy, like a human body, requires continual inputs of high-quality energy and materials

In thermodynamic terms, these inputs are the low-entropy energy and material throughput we need to drive the system. Entropy is key to understanding the logic of the steady-state economy. According to the first law of thermodynamics, energy cannot be created or destroyed. However, according to the second law of thermodynamics – the entropy law – the energy available to do work will decline in each transformation of energy. As Daly writes, “Were it not for entropy, we could burn the same gallon of gasoline over and over, and our capital stock would never wear out” (1991: 36). The entropy law teaches us that we can never create a perpetual motion machine, and we can never achieve perfect recycling of materials. As we burn fossil fuels, we use up our terrestrial stocks of high-quality energy. Once this “ancient sunlight” is used up, or too expensive to use, we must learn to rely on the flow of solar energy that we receive each day from the sun. This flow of solar energy can be converted to electricity using renewable energy sources like solar photovoltaics, wind turbines, and hydroelectric power production (see Energy Consumption Behavior). Conventional economics ignores our reliance on low-entropy energy and materials, a mistake that leads economists to pursue the never-ending growth of consumer and producer goods. Ecological economists like Herman Daly explore how we can build economies that operate within the flow of renewable energy and resources (see Ecological Economics)

History

Daly built his concept of a steady-state economy on the work of his PhD supervisor Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen, who identified entropy as the ultimate cost of economic activity. He was likewise influenced by the work of Kenneth Boulding and his conception of a “spaceman economy” that must operate within the finite limits of the Earth.

Herman Daly was not the first economist to discuss the possibility of a steady-state economy. Daly points back to John Stuart Mill (1848) and his writings on the subject in The Principles of Political Economy:

I cannot … regard the stationary state of capital and wealth with the unaffected aversion so generally manifested towards it by political economists of the old school. I am inclined to believe that it would be, on the whole, a very considerable improvement on our present condition.

Mill, like Daly, argues that growth involves increasing costs. Both Mill and Daly also argue that a steady (or stationary) state of population and artifacts would not mean the end of human progress. Mill wrote:

It is scarcely necessary to remark that a stationary condition of capital and population implies no stationary state of human improvement. There would be as much scope as ever for all kinds of mental culture, and moral and social progress; as much room for improving the Art of Living, and much more likelihood of its being improved, when minds ceased to be engrossed by the art of getting on.

Different Perspectives

Theories of complexity and adaptive resilience challenge the steady-state economy proposed by Daly. In a steady-state economy, humanity works to find a level of throughput at which we avoid passing what would now be called “planetary boundaries”, those critical thresholds after which great calamity befalls human civilization. Existing at this level would assume a balanced view of nature where we can stay within limits and maintain stability. However, ecosystems also experience random, stochastic change, and dynamic instability. A forest may grow to maturity, begin aging and decaying, and then experience a fire that burns its aging structures, leaving a meadow where the potential for new growth begins anew. This process of adaptive cycles was called Panarchy in a key text by Lance Gunderson and C.S. Holling, who envision our world as a dynamic, ever-changing place in which systems can be more or less resilient. Rather than working toward a steady-state economy, we might work to build a resilient economy, in which we plan for the unexpected, learn from our mistakes, and recognize the dynamic nature of Earth systems.

Application

To implement a steady-state economy, Daly proposes three institutions:

- A system of “transferable birth licenses” would control human population growth. This institution was partially established in China with its one-child policy, although China’s policy lacked a mechanism for transferring the right to have a child from one family to another. This policy proposal attracts criticism from conservative religious circles for encouraging birth control and from progressive circles for threatening women’s ability to choose how many children they have.

- A system of “depletion quotas”, auctioned by governments, would control the rate of energy and material use and depletion. The idea of depletion quotas for key energy and materials has not been pursued widely, though cap-and-trade systems are used to restrict emissions of pollution that result from burning fossil fuels (see Personal Carbon Allowance, Carbon Inequality).

- To ensure inequality does not worsen, Daly proposes minimum and maximum income limits and a maximum limit to personal wealth. In a steady-state economy, we cannot depend on a growing stock of economic artifacts to raise the living standards of the poor. When the pie is not growing larger, we must ensure a fair distribution of the pie. Minimum incomes have gained prominence with calls for a universal basic income. Maximum limits on income and wealth have not been as widely pursued (see Household Income Versus Carbon Footprint, Life Satisfactions Versus Income, and Fair Consumption Space).

Apart from Daly’s suggestions, scholars such as Peter Victor have worked to detail the policies that would allow countries to enhance quality of life, while achieving sustainability goals like eliminating greenhouse gas emissions (see also Well-being Economy). Victor recommends policies such as a reduced workweek that allows more leisure time and reduces a key labor input into the economic production process (see Work-Life Balance). Tim Jackson makes similar policy proposals and Victor and Jackson collaborate on modeling policies that can achieve stable, non-growing economies. Kate Raworth’s Doughnut Economics concept similarly helps conceptualize an economy that operates within planetary boundaries and that meets the needs of the world’s population. The Degrowth movement advocates for simple lifestyles that require lower levels of consumer and producer goods.

Further Reading

Boulding, K.E. (1966). The economics of the coming spaceship earth. In H. Jarrett (Ed.), Environmental quality in a growing economy, pp. 3–14. Resources for the Future, Johns Hopkins University Press.

Daly, Herman E. (1991). Steady-state economics. 2nd ed. Island Press.

Jackson, T. (2017). Prosperity without growth: Foundations for the economy of tomorrow. 2nd ed. Routledge.

Raworth, K. (2017). Doughnut economics: 7 ways to think like a 21st century economist. Chelsea Green Publishing.

Victor, P.A. (2019). Managing without growth: Slower by design, not disaster. 2nd ed. Edward Elgar Publishing.