Definition

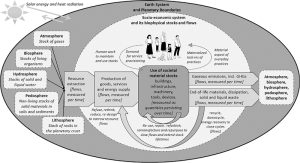

The concept of societal material stocks refers to the long-lived biophysical basis of society, from individual buildings, cars, machinery, or computers to entire settlements and infrastructure systems. Because those stocks lock in production and consumption patterns over years to decades, their role in transformations toward sustainable consumption patterns in everyday practices and the high-level provision of services to ensure well-being is crucial (Figure 27.1; see Social Practice Theory, Well-being Economy).

For example, safe and affordable housing first requires constructing a building and its water and electricity supply networks which turn flows of construction materials into long-lived material stocks. Then, energy flows are needed to heat and cool living spaces, based on the thermal performance of the building and the inhabitant’s demand for thermal comfort. Buildings also require maintenance, repairs, and component replacement. The building’s location, with its access to mobility infrastructure and places people want to reach, determines the mobility practices of its inhabitants and thus locks in future energy flows for transport (see Sustainable Mobility, Urban Planning and Spatial Allocation). Those mobility practices then shape the required material stocks and flows in infrastructure systems and vehicles, including upstream energy and material flows in industry and construction. Each cycle of use, maintenance, and repair causes waste and emissions. At the end of life, a building might be demolished, causing further waste flows which might be recycled, landfilled, or otherwise disposed of.

From a systems perspective, the concept of societal material stocks is usually pragmatically defined as covering those products used and maintained for more than a year (Figure 27.1). Multiple aspects are measured, for example, physical and functional units of service provisioning such as kg of mass, m² of living space, purpose, or economic value and ownership. In the literature, societal material stocks are also called in-use stocks, manufactured and fixed capital, anthropomass, technomass, technosphere, built environment, infrastructure, or artifacts. The concept of stocks is also used in the natural sciences, for example, to quantify carbon stored in forests, or to measure resource deposits. Stocks of natural resources are also valued in economic terms by economists, who then refer to them as natural capital. Those “natural” stocks exist without humans investing work into their creation and maintenance (Figure 27.1).

Flows of material resources cover metals and ores, biomass, non-metallic minerals, fossil fuels, and water, which are extracted from the Earth System and its natural stocks of resource deposits (Figure 27.1). Material flows are processed into various products by industry using stocks of machinery, infrastructure, and energy. Products may be “consumed” within a short time, for example, for energy provision in the form of motor fuels or electricity, as drinking water, packaging material, or fertilizer. Each of these products eventually turn into waste and emissions. Alternatively, products that are used for a longer time accumulate as societal material stocks, creating unavoidable lock-ins and path dependencies (see above). Multiple aspects of resource flows can be measured, such as mass, value, environmental impacts, purpose, and ownership. However, in contrast to stocks, flows are always measured per unit of time, commonly per year.

History

Since the beginning of the 20th-century economists have dealt with societal stocks, focusing on their monetary market-based transaction value. They address questions of investment, value depreciation, technological capacity, and substitution. They usually view the economy as separate from the environment and hardly acknowledge limits to the growth of the economy as valued in monetary terms (see Ecological Economics and Degrowth).

Alternatively, the crucial role of societal material stocks for sustainable production and consumption was already identified in the 1960s. For example, Kenneth Boulding’s seminal essay on the “Economics of the coming Spaceship Earth” argues that

the ultimate measure of the success of the economy is … the nature, extent, quality, and complexity of the total capital [material] stock … what we are primarily concerned with is stock maintenance, and any technological change which results in the maintenance of a given total stock with a lessened throughput [of material and energy flows ultimately turning into waste and emissions] … is clearly a gain.

This alternative systems-based perspective on society-nature interactions views society and its economy as highly interdependent parts of the Earth System, subject to natural laws and confined to a materially closed, but energetically open planet Earth (Figure 27.1; see Steady-State Economy). Several research approaches emerged from this perspective, aiming to identify opportunities for providing the services required for well-being with a reduced energy and material demand.

System dynamics, for instance, incorporates material stocks and flows to describe a system’s resilience and potential transition pathways, as exemplified in the 1972 Limits to Growth work by Meadows et al. Life cycle assessments (LCA) analyze and compare the environmental impacts of products and service provisions, often by allocating or depreciating stocks over time. Environmentally-Extended Input-Output Analysis (EE-IOA) models how supply chains link resource flows through production to consumption around the world, but mostly struggle to incorporate material stock dynamics. Material and energy flow analysis (MEFA) analyzes societal material stocks and resource flows of socio-economic systems, from specific production and consumption systems to the urban, national, and global economy. Recently, macroeconomic and integrated assessment models have also been extended toward covering biophysical stock-flow dynamics (Wiedenhofer et al., 2024). These efforts are found in the related fields of Ecological Economics, Input-Output Analysis, Social Metabolism, Life Cycle Assessment, Industrial Ecology, Complex Systems Research, and Sustainability Science.

Different Perspectives

The mainstream economic perspective on societal material stocks and flows has several critical limitations for sustainable production and consumption research and practice. Firstly, market-based economic transaction values might fluctuate strongly, without any physical change to the actual material stock. For example, the collapse of the US housing market in 2009–2010 resulted in catastrophic losses of monetary value, destabilizing the global economy; however, the physical buildings and their potential for service provisioning for well-being did not change (see Foundational Economy). Similarly, the value of a building also often increases, without any actual physical changes to it. Secondly, use values are context- and actor-specific, which do not directly translate into the monetary transaction values of service provisioning for human well-being. For example, safe and affordable housing for low-income people is “worth” much less in monetary terms, than a villa for the super-wealthy. Thirdly, monetary depreciation over time, as used in bookkeeping, implies decreasing the value of a stock, while physical functionality and realized lifetimes differ substantially. For example, the moment someone buys a new car, it immediately loses substantial monetary value due to now being second-hand, while the actual car is still the same.

Source: Produced by the author

The alternative systems-based perspective on society-nature interactions focuses on a biophysical and stock-flow consistent understanding of sustainable production and consumption, inequality, service provisioning for well-being, as well as resource efficiency and the potential criticality of specific resources. This perspective emphasizes (i) strong sustainability and the intrinsic value of nature in different contexts, and (ii) the need for deep structural transformations to achieve internationally agreed-upon climate and biodiversity protection targets. It advances a biophysical perspective on society-nature interactions, distinct but complementary to monetary valuation. Analogous to any biological metabolism, it views societies as having to successfully organize energy and material flows to maintain, expand, and use its societal material stocks. Because most societal stocks are long-lived, they create lock-ins and path dependencies, as in the example about buildings and mobility above (see Urban Planning and Spatial Allocation). The composition, magnitude, and patterns of the biophysical society-nature interactions (i.e., the social metabolism) therefore determine society’s environmental pressures and impacts.

| Topic | Insight |

|---|---|

| Global stock dynamics drive resource use patterns | Societal material stocks have increased 26-fold over the last 115 years and continue to grow across the world. About half of global resource extraction is used to build and maintain material stocks. Another quarter are fossil energy carriers utilized for energy provisioning, and the remaining quarter is used for food provisioning. A very small share goes to dissipative uses such as lubricants, fertilizer, or chemicals used in agriculture. |

| Energy-materials-GHG nexus | About one-third of the global primary energy supply and subsequent GHG emissions are generated by the production and maintenance of material stocks. The remaining two-thirds are used to utilize material stocks of buildings, infrastructure, machinery, and other devices. |

| Resource-efficient everyday life and social practices | Service provisioning and everyday life practices rest on specific stock-flow combinations, which can be more or less ecoefficiently designed and utilized (see Choice Editing). Because stock-flow relations are controlled by societal actors, and organized via property rights and economic relations, questions of power, justice, inequality, and fairness need to be addressed. This is relevant to understanding the malleability and transformation options of provisioning systems and practices to achieve sustainable production and consumption patterns. |

| Material stocks as leverage points for more sustainable resource use | Mitigating resource use and emissions requires halting the further expansion of stocks, especially in higher-income countries with already substantial accumulated material stocks. As long as material stocks are growing, more primary virgin resources are required, because recycling can only utilize end-of-life waste from stocks built years or decades earlier. Those end-of-life stocks are necessarily much smaller in a growing system. Stabilizing stocks requires radically re-designing and densifying existing settlement structures, and stopping any new construction on previously not built-up land. This would halt soil sealing and associated environmental problems, such as loss of fertile land and resilience against natural disasters. |

| Creating positive lock-ins | Creating positive lock-ins into highly ecoefficient service provisioning systems is a key challenge for a sustainable future. For lower-income contexts requiring better and more material stocks to achieve minimum decent living standards, they must avoid resource-intensive, car-dependent, and sprawling settlement patterns. Higher-income contexts need to rapidly transform their already-existing stocks. |

| Toward a Sustainable Circular Economy | A sustainable circular economy needs to narrow, slow, and close socio-economic material cycles (see Circular Economy and Society). This should mitigate energy use and GHG emissions, as well as other associated environmental pressures and impacts. While a perfectly circular economy is thermodynamically impossible, it can still serve as a useful benchmark to strive for. Narrowing material cycles include sufficiency and ecodesign, building standards, and infrastructure planning. Slowing cycles require lifetime extensions of existing stocks, for example via re-use, repair, and refurbishment. Closing cycles require improved recycling systems, as well as restorative land use practices improving soil health and biodiversity. |

| Stocks are necessary, butwill always cause flows | Even stabilized material stocks require continuous inputs of primary materials and energy for their use, maintenance, and service provisioning. Providing for minimum universal social standards around the world also requires a certain amount of material stocks to still be built. However, there are always unavoidable losses and waste by-products during production and end-of-life waste collection, which cannot be fully recovered nor completely recycled, including quality reductions due to impurities, alloying, and complex chemical properties of products. |

| Criticality of materials and metalloids | Metals and metalloids are crucial for various modern technologies required for renewable energy systems and digitalization. Nowadays, more than two-thirds of all known elements are used, with little recovery nor recycling occurring. Many metals of high concern are used for highly specialized applications with no effective substitutes. |

Applications

Table 27.1 presents insights into topics developed from making stocks and flows explicit in sustainable consumption and production research.

Further Reading

Charpentier Poncelet, A., Helbig, C., Loubet, P., Beylot, A., Muller, S., Villeneuve, J., Laratte, B., Thorenz, A., Tuma, A., & Sonnemann, G. (2022). Losses and lifetimes of metals in the economy. Nature Sustainability, 5(8), 717–726. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-022-00895-8.

Haberl, H., Wiedenhofer, D., Pauliuk, S., Krausmann, F., Müller, D.B., & Fischer-Kowalski, M. (2019). Contributions of sociometabolic research to sustainability science. Nature Sustainability, 2, 173–184. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-019-0225-2.

Pauliuk, S. (2018). Critical appraisal of the circular economy standard BS 8001:2017 and a dashboard of quantitative system indicators for its implementation in organizations. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 129, 81–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2017.10.019.

Wiedenhofer, D., Smetschka, B., Akenji, L., Jalas, M., & Haberl, H. (2018). Household time use, carbon footprints, and urban form: A review of the potential contributions of everyday living to the 1.5 °C climate target. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, Environmental Change Assessment, 30, 7–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2018.02.007.

Wiedenhofer, D., Streeck, J., Wiese, F., Verdolini, E., Mastrucci, A., Ju, Y., Boza-Kiss, B., Min, J., Norman, J., Wieland, H., Bento, N., Godoy León, M.F., Magalar, L., Mayer, A., Gingrich, S., Hayashi, A., Jupesta, J., Ünlü, G., Niamir, L., Cao, T., Sugiyama, M., & Wilson, C. (2024). Industry transformations for high service provisioning with lower energy and material demand: A review of models and scenarios. Annual Review of Environment and Resources, 49. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-environ-110822-044428.