Definition

Values are the deeply held beliefs and principles that guide our decisions and influence our behaviors. They shape how we perceive the world, interact with others, and pursue goals as individuals. They also influence how the protagonists of society – individuals, communities, institutions, and nations – interact. Values are not static. They can evolve, changing as we learn, grow, and are exposed to new experiences. Values can also be a source of conflict in that some strongly held values may conflict with others, forcing the prioritization of certain values over others.

Values are hierarchical in that we hold some values more strongly than others. Similarly, some are considered to be “higher” than others. For instance, values that are considered to contribute to collective human flourishing, such as compassion, generosity, and justice, may be considered higher, whereas values that primarily serve the self, such as greed, avarice, or lust for power, could be considered lower. While addressing the source or origin of values is deeply complex, some key sources include family life, society and social norms, formal education, religion, and spirituality. Values can be considered a cornerstone of society.

Historically, values have served as a moral compass, influenced social norms, acted as a basis for developing social cohesion, provided individuals with meaning and purpose, and created a sense of identity. More recently, the wider discourse on values has become predominantly concerned with economic, intrinsic, and utilitarian value – engines of a growth-driven materialistic, economic paradigm.

Considering values through the lens of sustainable consumption, it is important to both unpack and apply currently often overlooked, but societally important, values – such as justice, trust, sufficiency, contentment, simplicity, and moderation (see Climate Justice and Voluntary Simplicity). These and others could prove fruitful territory for empowering a swifter and more inclusive transition to more sustainable patterns of consumption and development. While not unique to religion or spirituality, the aforementioned values are held dear by many religions and spiritual movements.

History

Throughout the ages, values have been a key force in human existence. Looking across religious and spiritual movements, for example, there are clear and direct links between spiritual teachings that lead to values being put into practice. Buddhism teaches that all beings are interconnected and the suffering of one is the suffering of all. This has placed compassion and non-violence at the core of Buddhist practice, often manifested in actions such as vegetarianism or advocacy to abolish nuclear weapons (see Protein Transition).

Drawing from Christ’s emphasis on love for one’s neighbor and selfless service, many Christians express their faith through charitable actions or social justice work, evidenced by the work of organizations such as Catholic Relief Services or Church World Service. The Bahá’í Faith adopts unity as both a goal and a mode of operation, such that many Bahá’í communities around the world, through spiritual capacity-building initiatives for children, youth, and adults, work to create communities in which no form of prejudice is acceptable. Indigenous cultures and beliefs often see a deep connection between the spiritual and natural worlds, which helps foster values such as harmony, moderation, and respect for nature (see Buen Vivir and Buenos Convivires).

These are just some brief examples across the breadth of spiritual experience that illustrate how deeply connected spirituality and values are. Even in recent years, as the number of adherents to mainstream religions has fallen in the United States, 83% of US adults believe we have a soul or spirit in addition to our physical bodies and 81% believe there is something spiritual beyond our world. This trend seems consistent across economically advanced countries (see the Pew-Templeton Global Religious Futures project). This trend further suggests that, whether religious or not, a sizable number of people see humanity’s existence as being governed not only by physical and material forces but also by spiritual and moral considerations. Spirituality is something more intangible and less organized than traditional religion, but no less a potent force in the promotion and adoption of values.

Different Perspectives

Any discussion of values is inherently complex, multidimensional, subjective, and relative – influenced by personal, cultural, historical, and other factors – and reflects the complexity of the myriad systems underpinning our world. They are difficult to measure and can evolve. In behavioral sciences, values are included and operationalized in seminal theories and models. For instance, Schwarz proposed a two-dimensional typology with 10 value clusters, ranging from hedonism to achievement power and benevolence (see Hedonic Treadmill). Based on this and Stern’s Model, Steg and colleagues identified and continuously tested biospheric, altruistic, egoistic, and hedonistic values as the drivers for pro-environmental action.

Recognizing this complexity can support a more nuanced and productive conversation on the role of values in modern society (see Box 53.1).

Box 53.1. Toward a global ethic

Discussing the role of values, the World’s preeminent interfaith organization, the Parliament of the World’s Religions, released the statement “Toward a Global Ethic” which posited that there are universal, shared religious values. The document suggests that justice, equality, and solidarity are key to the creation of a just economic order. To counter overconsumption, the document calls on people to strive for fairness in consumption and to live moderate lifestyles.

See Parliament of the World’s Religions. (1993). Towards a Global Ethic: An Initial Declaration.

The complexity of value systems is evident in the conflicting, competing, and overlapping value sets inherent to many social actors. The move of many governments toward policy and legislation that promote sustainable lifestyles can be seen to conflict with the goal of corporations to maximize profitability (see The Role of Business). Religious actors promoting detachment from material possessions can be perceived as a threat to consumer society. However, many facets of the religious and spiritual experience, such as pilgrimage or mindfulness, are becoming commodified (see Spiritual Consumption).

By seeking to understand the conflicts and overlaps between different social actors, we may be able to identify shared values that could serve as departure points for united action toward a sustainable society. These values could include the common good, human nobility, and intergenerational justice.

The development paradigm that has largely prevailed since the end of World War II – an approach rooted in the extraction of natural resources and endlessly increasing standards of living – is no longer fit for purpose. The consumerist, technological, and macroeconomic trends that have defined much of the last century have driven increasing global inequality and brought us to the point of environmental collapse (see Carbon Inequality). However, just because a certain paradigm is no longer fit for purpose does not mean that suitable alternatives have been identified.

Application

Multinational organizations are increasingly looking toward values-inspired approaches to advancing global systems. Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) Target 17.19 seeks to spur the development of metrics that look beyond Gross Domestic Product and measure sustainable development. In addition to the UN, the EU has begun to champion the “Beyond GDP” movement, which could see the reimagining of prosperity through the promotion of measures such as equality, fairness, inclusivity, and happiness (see Well-being Economy, Degrowth). To advance such views in relevant international forums, such as the UNFCCC Conference of the Parties (COP), spaces could be created to explore what values-based measures and metrics are more fit to purpose for systems that seek to center sustainable consumption and, more broadly, sustainable development.

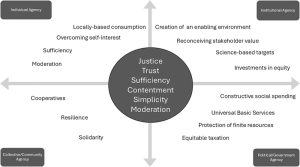

One potential tool in identifying and promoting alternative development pathways is a values-based framework to enable sustainable consumption. Such a framework, built upon the values mentioned above in the definition, and addressing the agency enjoyed by major protagonists of society – the individual, communities/collectives, institutions, and government – could allow these protagonists to understand the needs of each and provide values-based lines of action, as well as concepts, to build more sustainable patterns of consumption.

Figure 53.1 (a simple conceptual framework) is an attempt at a visual representation of what this chapter discusses. It is based upon the author’s professional experience of multiple conversations with like-minded civil society, faith-based, and non-governmental organizations who look to principled and values-based responses to pressing societal challenges. It suggests that certain underlying values could serve as the foundations for a range of practical strategies. By considering the implications of sufficiency or contentment in their daily lives, individuals could make decisions that prioritize collective interests over individuals. Communities and collectives, by seeking to build trust, could begin to build more social and economic cooperative structures (see Community Supported Agriculture, Alternative Consumer Cooperatives). Societal institutions such as universities and private enterprises, predicated on moderation and sufficiency, may begin to look at other forms of shareholder value or develop a deeper understanding of what is meant by equity. Governments, seeking to build justice, could address a great many ills through restructuring social spending or protecting finite resources (see Universal Basic Services, Foundational Economy).

Ultimately, recognizing that the climate crisis and other pressing societal challenges are more than just technical problems, but are also the result of incompatible values, could open up a vista for new forms of sustainable action. If people were to consider the climate crisis as a condition borne out of greed, inequality, and injustice, it could provide a blueprint for how they develop their potential to respond to a changing world while also working to refine and enhance the communities and institutions in which they are engaged. The prevalent structures and processes built on a different logic must be reshaped and adapted to facilitate actors to act upon a potentially (newly gained) value-driven agency. To summarize, much remains to be learned about frameworks that center spiritual values and ethical principles that can be both developed and applied to effect change.

Source: By author

Further Reading

Bahá’í International Community (BIC). (2022). One planet, one habitation: A Bahá’í perspective on recasting humanity’s relationship with the natural world. Available at: bic.org (accessed: 13 December 2024).

European Commission. (2007). Beyond GDP. Available at: https://sustainable-prosperity.eu. (accessed: 13 December 2024).

Jenkins, W., Tucker, M.E., & Grim, J. (2017). Routledge handbook of religion and ecology. London: Routledge.

Pew Research Center. (2022). Key findings from the global religious futures project. Available at: https://pewresearch.org (accessed: 13 December 2024).

Tucker, M.E., & Grim, J. (2023). Yale forum on religion and ecology. Yale Center for Environmental Justice. Available at: https://fore.yale.edu (accessed: 8 January 2024).