Definition

Work-life balance can be described as a state in which individuals feel satisfied with how they allocate their time and energy to work, family, and social commitments. Achieving work-life balance is directly connected to the broader issue of working time, especially for individuals with limited control over their work-time arrangement. Working time reduction is key to enabling a transition to more sustainable economic systems that do not require perpetual increases in consumption and production. Work-life balance is important in shaping consumption and production practices that contribute to reducing environmental degradation as well as improving personal health and life satisfaction (see Well-being and Life Satisfaction Versus Income).

History

The issue of working time and work-life balance are fundamental to discussions of sustainable development. The term “work-life balance” was coined by Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis in the early 1900s with his arguments about scientific management and worker productivity in regard to railroad rate increases. The issue was also very important to John Maynard Keynes, who famously predicted in 1930 that by 2030, people would spend around 15 hours a week at work with a drastic increase in leisure time as their material needs were met.

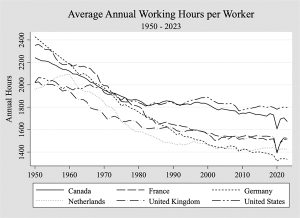

While Brandeis and Keynes were primarily concerned with issues related to labor productivity, leisure time, and life satisfaction, Juliet Schor’s (1992) seminal book, The Overworked American: The Unexpected Decline of Leisure, connected the issue directly to broader concerns of sustainable development that included consumerism, inequality and environmental decline. In the book, Schor traces the issue of working time throughout history and notes that working time drastically increased with the rise of capitalism and began to decline in Western countries in the mid-19th century. This homogenous decline continued until the late 1970s with the rise of neoliberal economic policies that favored reduced taxation for corporations and the wealthy, reduced regulations, and emphasized individual responsibility. From then, while working hours continued declining slowly in some countries such as Germany, France, and the Netherlands, they became stable or increased in many others including the United States, Canada, and the United Kingdom. The result is a work-life balance that suppresses leisure time in favor of work. Figure 17.1 visualizes the trends in working time across a selection of developed countries from 1950 to 2023.

Given these trends, the appeal and potential of working-time reduction derives largely from the fact that declines in working time have stalled despite rapid increases in labor productivity (defined as the amount of GDP produced per hour of work). For example, based on data from the OECD, in the United States, it is now possible to reproduce the 1970 standard of living in less than half the time it took that year, due to improvements in labor productivity. While there was a 119% increase in labor productivity in the United States, there was only about a 7% decrease in average hours worked. This suggests that there is much room to reduce hours and improve work-life balance.

Source: Conference Board’s, Total Economy Database (2024)

Different Perspectives

Proponents of a working-time reduction suggest that it has the potential to be a triple-dividend sustainability policy that enhances social, economic, and environmental well-being (see Well-being Economy). Starting with social well-being, reducing working time can improve health outcomes and life satisfaction. There are many reasons for this. The first is that the structure of work, especially the problem of over-work, often produces greater levels of stress and work-related anxieties, which are then translated to greater incidence of health problems. These include a lack of sleep, heart disease, or cancer, as well as a higher likelihood of unhealthy coping behaviors, such as tobacco use, illicit drug use, or alcohol consumption. Time poverty, or the lack of free time, is an important issue here. The adverse effects of a lack of free time include a lack of exercise, sleep, and quality time with family and loved ones, as well as increased odds of unhealthy eating, particularly fast food.

The first economic benefit of reduced working hours is how it can mitigate unemployment. Instead of needing to create new jobs to absorb displaced workers, available work could be spread out among workers. This is particularly important in connection to degrowth, to avoid large disruptions to employment. There are also implications for unemployment in a growth economy, particularly with the rapid rise of artificial intelligence and automation.

Finally, working time is also understood to affect environmental outcomes through two pathways, known as scale and compositional effects. The scale effect is how longer working hours contribute to overall economic growth. Longer working hours lead to more production, consumption, and overall GDP growth. The compositional effect is how working time structures the composition of household consumption. Similar to the time poverty approach when considering the relationship between working time and health, time-stressed households are more likely to opt for consumption choices that might save time but are more ecologically damaging. One clear example of this is in transportation, where the more time-intensive options (biking, walking, or public transportation) are much better environmentally compared to the time-efficient option of driving a car (see Sustainable Mobility).

It should be noted that there are several unresolved issues in this area of research. The first is the issue of rebound effects. It is possible that systematically reducing working hours will lead to greater consumption. For example, if the free time that comes from reduced working hours leads to more vacations or travel, it could result in greater environmental impacts. Another unresolved issue is the feasibility of achieving a working time reduction. Not only are many businesses fundamentally opposed to reducing working time for fear that it could lead to declining profits, but there is the issue of inequality as well. While reducing working hours, and thus income is possible for high-income workers, it is not as feasible for those at the bottom of the income ladder who struggle to make ends meet. Similarly, it is unclear how working-time reduction may differentially benefit men and women. Aside from the gender pay gap, women are still expected to perform more household labor than men so time off from the formal labor market may not have the same benefits for women as for men (see Gender). Thus, a working-time reduction must be accompanied by other structural changes that address broader issues of inequality as well.

Application

Conditions and structures of work are evolving quickly, with various initiatives introduced to improve work-life balance, showing their potential sustainability benefits. A prominent example is the four-day week trial, where participating organizations maintain pay at 100% while giving employees a meaningful reduction in work time (4 Day Week Global, 2024). Results from two landmark trials conducted in Iceland, one with 2500 public sector workers (2014–2019) and another with 440 workers (2017–2021), showed that workers took on fewer hours and enjoyed improved work-life balance, greater well-being, while maintaining productivity. Similarly, a 2022 UK trial, comprising 61 companies and about 2900 workers, reported enhanced work-life balance and well-being, and healthy growth of company revenue over the six-month trial period.

In addition to these positive influences, evidence gathered from the United States and Canada involving 41 companies between 2022 and 2023 demonstrated the impact of reduced work time on sustainable consumption. Fewer employees commuted to work by car during the trial, and 42% of participants engaged more in environmentally friendly activities, such as buying ecofriendly products, recycling, and walking and cycling. No “travel rebound” effect was identified among these participants (e.g., by traveling more in their extra free time). The trials have been running on six continents, and their successful stories support the feasibility and sustainability implications of reduced work hours.

It is also important to note that in addition to work time reduction, there is a trend toward flextime and remote work, which was accelerated by the COVID-19 pandemic and has been increasingly adopted by more workplaces for its perceived benefits to work-life balance. These work-life balance initiatives are expected to affect individuals’ interactions with material objects, such as encouraging sustainable household practices and their involvement in personal fulfillment and social relationships, including developing personal hobbies and broader public engagement.

Further Reading

4 Day Week Global. (2024). Research – 4 day week global. Available at: https://www.4dayweek.com/research (accessed: 2 June 2024).

Fitzgerald, Jared B., Givens, Jennifer E., & Briscoe, Michael D. (2024). Working time and the environmental intensity of well-being: A cross-national analysis of high-income OECD Countries, 1970–2019. Sociology of Development, 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1525/sod.2023.0048.

Schor, Juliet B. (1992). The overworked American: The unexpected decline of leisure. Basic Books.

The Conference Board. (2024). “Total Economy Database Data.” Available at: https://www.conference-board.org/data/economydatabase/index.cfm?id=27762 (accessed: 2 June 2024).

Victor, Peter A. (2019). Managing without growth: Slower by design, not disaster. 2nd ed. Edward Elgar Publishing.