Definition

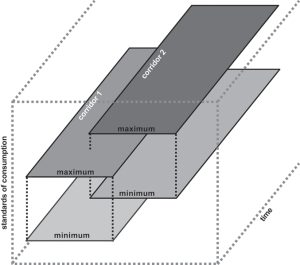

The concept of Consumption Corridors (CC) provides a framework for sustainable consumption governance. It suggests achieving sustainability by developing and implementing corridors of consumption, defined by consumption minima and maxima. The lower boundaries are meant to allow every individual to satisfy their needs, and thus to live a life they value by determining what every individual must have access to. The upper boundaries are meant to prevent the consumption by individuals or groups from inhibiting or affecting the well-being of other individuals, living now or in the future. To that end, they determine thresholds that if (quantitatively or qualitatively) trespassed adversely impact the quality of life of other individuals by putting others’ minima at risk. The space between these boundaries is what is referred to as a consumption corridor (Figure 30.1). This space leaves room for individual life plans and choices, for individual freedom (see Freedom of Choice). The concept of CC posits quality of life and justice as criteria to define minima and maxima of consumption. Both the lower and the upper limits refer to satisfiers (see Box 30.1).

The concept of CC offers a new way of organizing societies and their production and consumption systems, to ensure a good life for all people at present and in the future. It is not a single policy measure but a framework for developing policies. While suggesting far-reaching changes and acknowledging the necessity of protecting the natural environment, it has a strong focus on well-being and justice and neither adopts a narrative of renunciation nor imposes specific lifestyles. It offers a narrative for sustainable consumption governance that explicitly focuses on achieving (the vision of) a good life (salutogenic), rather than focusing primarily on avoiding damage (pathogenic).

Box 30.1 Needs and satisfiers

Distinguishing needs from satisfiers is at the core of a scholarly discourse about quality of life that is based on the notion of needs. A well-known proponent of this difference is Manfred Max-Neef. Satisfiers are the means that are used to satisfy needs. Satisfiers are what people do and what they make use of to live a good life, and can be both material and immaterial (i.e., legislation). Products, services, practices, and infrastructures are satisfiers. While needs are assumed to be universal and stable, satisfiers are not; they are assumed to change over the course of time but also depend on historical and societal context.

While a considerable part of the public discussion on human well-being revolves around satisfiers and confuses them with needs, the concept of CC draws attention to clearly distinguishing needs from satisfiers. It seeks to change and replace satisfiers that lead to unsustainable patterns of consumption. It also suggests initiating a societal debate about satisfiers and about how societies organize to satisfy people’s needs.

Source: Di Giulio, A., & Fuchs, D. (2014). Sustainable consumption corridors: Concept, objections, and responses. GAIA – Ecological Perspectives for Science and Society, 23(S1), 184–192. https://doi.org/10.14512/gaia.23.S1.6

History

The concept of CC emerged as one result of an inter- and transdisciplinary research program (2008–2013) funded by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF). Some 150 academic and experience-based experts, covering more than 15 scientific disciplines and a broad diversity of areas of practice, investigated different aspects of sustainable consumption and engaged in integrating their results. One of the integrated results were eight recommendations (“Konsum-Botschaften”: consumption messages), each presenting a pathway toward sustainable consumption. The drafts of these messages were discussed and validated with 70 representatives from the arenas of politics, administration, the economy, and civil society organizations. In one of these messages, the concept of CC is introduced (“Korridor-Botschaft”, https://doi.org/10.48350/49106).

Since its launch in 2013 in Germany, the concept of CC has been introduced to a broad international audience and gained growing attention. It is used as guidance for exploring a broad spectrum of concrete fields of consumption, such as land use, urban mobility, park spaces, fashion, laundry, and meat consumption (see, for instance, the examples in Collection SSPP [2021]). Using the case of Switzerland, empirical work has been conducted to show how the concept would be received in one society (Defila & Di Giulio, 2020). On a regional level, the concept of CC has recently been taken up by the European Environment Agency (EEA, 2023). With a view to going beyond single fields of consumption, it has been discussed as a new paradigm to approach sufficiency (Lombardi & Cembalo, 2022) and as a promising concept to navigate the global land squeeze (Erb et al., 2024).

Different Perspectives

The concept of CC is related to sufficiency, and aligned with the principles of a well-being economy, as well as the concept of limitarianism developed by Ingrid Robeyns.

There are also concepts that the concept of CC is sometimes mixed up with. One of these is Doughnut Economics (DE) developed by Kate Raworth, which draws on the concept of Planetary Boundaries (PB), promoted by Johan Rockström and colleagues. Another more recent one is Fair Consumption Space (FCS). DE operates with inner and outer boundaries, FCS with underconsumption and overconsumption.

In contrast to these concepts, the concept of CC adopts a salutogenic approach and is deeply informed by quality of life and justice. Although acknowledging the vulnerability of (natural and societal) resources, both the lower and the upper boundaries of CC are justified by human well-being and justice. The concept of CC integrates the notions of quality of life, individual freedom, vulnerability of resources, and justice with a view to developing public policies.

Both DE and PB primarily aim at averting damage, pursuing a pathogenic approach. Neither DE nor PB ingrain the notions of a good life and justice as overarching criteria, they do not draw on the needs-satisfier distinction, and they do not explicitly deal with the question of individual freedom and diversity. According to PB, the destabilization of the natural conditions that mark the Holocene epoch must be averted. In DE, PB are used to define the “ecological ceiling”, and the purpose of this ceiling is averting “planetary degradation”. Similarly, FCS defines overconsumption as consumption that harms planetary systems. The other damage that has to be averted, according to DE, is “critical human deprivation”, and this leads to the doughnut’s inner boundary. To define this boundary, it suggests drawing on the social priorities defined by the Sustainable Development Goals.

Another difference concerns the question of how to determine the limits. While in DE the boundaries are defined by either natural scientists (outer boundaries) or by (international) political bodies (inner boundaries), the concept of CC posits that the minima and maxima of consumption have to be societally negotiated by adopting a participative approach. Determining them has to be based on an inter- and transdisciplinary collaboration that integrates a broad diversity of academic and non-academic perspectives and knowledge systems.

Application

The concept of CC challenges satisfiers, it does not challenge human needs. In addition to being a framework for governance, it is an invitation to reflect upon how quality of life is achieved and discussed in societies (see Box 30.2). It emphasizes the importance of the social contract within and across nations, and it posits that not damaging others is not enough. It points out the necessity for limits while recognizing that there will always be some inequality and diversity in how needs are satisfied in a given society. The approach thus acknowledges that there is no absolute level of sustainable consumption, but always a relative one.

The concept of CC offers a promising way forward that resonates with a broad diversity of people, but with a view to its implementation, some crucial questions remain to be explored. One is the question of how to bridge the divide between a comprehensive approach to quality of life, on the one hand, and approaches that focus on the natural environment, on the other, in ways that provide a firm foundation on which to build when determining minima and maxima of consumption. Another, addressed by a number of recent contributions to the CC literature, is the question of how to initiate such a deep transformation and where to start.

Box 30.2 The Theory of Protected Needs (PN) – a concept of quality of life that is a suitable fundament for defining consumption corridors

The concept of CC presupposes, first of all, that a universal definition of human well-being is possible and that it should not be reduced to basic needs. Such a definition must provide solid ground to proceed from in determining the satisfiers (and resources) that every individual must be provided with (minima) and that must not be put at risk (maxima). The Theory of PN (Di Giulio & Defila, 2020) provides a theory of well-being that serves this purpose.

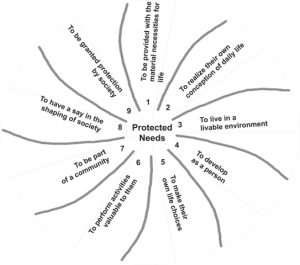

The Theory of PN provides a list of universal (and not hierarchical) needs. These needs are called protected because they claim to be (1) needs that deserve special protection within and across societies since they are crucial to human well-being, and they claim to be, at the same time, (2) needs for which special societal protection is possible since they are needs that a government or community can reasonably be made responsible for. The Theory of PN proposes nine universal needs. Each is specified by a thick description. The needs denote what individuals must be allowed to want (Figure 30.2), and the thick descriptions describe the possibilities individuals should be provided with. Concurring with a needs approach, the nine needs are ends in themselves. That is, they cannot be further reduced and they are non-substitutable. The nine needs are context-sensitive despite being universal: the thick descriptions serve as a starting point for their cultural and historical adaptation. Empirical evidence shows that these needs resonate in different cultural contexts.

https://vocabulary.hotorcool.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/12/249cedb4-47f9-497c-b446-244d543a97da-100x88.jpeg 100w, https://vocabulary.hotorcool.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/12/249cedb4-47f9-497c-b446-244d543a97da-340x301.jpeg 340w, https://vocabulary.hotorcool.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/12/249cedb4-47f9-497c-b446-244d543a97da-480x424.jpeg 480w, https://vocabulary.hotorcool.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/12/249cedb4-47f9-497c-b446-244d543a97da-200x177.jpeg 200w, https://vocabulary.hotorcool.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/12/249cedb4-47f9-497c-b446-244d543a97da.jpeg 543w" sizes="auto, (max-width: 300px) 100vw, 300px">

https://vocabulary.hotorcool.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/12/249cedb4-47f9-497c-b446-244d543a97da-100x88.jpeg 100w, https://vocabulary.hotorcool.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/12/249cedb4-47f9-497c-b446-244d543a97da-340x301.jpeg 340w, https://vocabulary.hotorcool.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/12/249cedb4-47f9-497c-b446-244d543a97da-480x424.jpeg 480w, https://vocabulary.hotorcool.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/12/249cedb4-47f9-497c-b446-244d543a97da-200x177.jpeg 200w, https://vocabulary.hotorcool.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/12/249cedb4-47f9-497c-b446-244d543a97da.jpeg 543w" sizes="auto, (max-width: 300px) 100vw, 300px">Source: Di Giulio, A., & Defila, R. (2020). The ‘good life’ and Protected Needs. In A. Kalfagianni, D. Fuchs, & A. Hayden (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of global sustainability governance, pp. 100–114. London. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315170237-9 ⏎

Further Reading

Collection SSPP. (2021). Consumption corridors: Advancing the concept and exploring its implications. In M. Sahakian et al. (Eds.), Sustainability: Science, practice and policy (SSPP). Available at: https://www.tandfonline.com/journals/tsus20/collections/consumption-corridors (accessed: 8 January 2025).

Defila, R., & Di Giulio, A. (2020). The concept of “consumption corridors” meets society – How an idea for fundamental changes in consumption is received. Journal of Consumer Policy, 43, 315–344. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10603-019-09437-w.

EEA (European Environment Agency). (2023). Conditions and pathways for sustainable and circular consumption in Europe. Briefing No. 11/2023. https://doi.org/10.2800/137584.

Erb, K.-H., Matej, S., Haberl, H., & Gingrich, S. (2024). Sustainable land systems in the Anthropocene: Navigating the global land squeeze. One Earth, 7(7), 1170–1186. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oneear.2024.06.011.

Lombardi, A., & Cembalo, L. (2022). Consumption corridors as a new paradigm of sustainability. Resources, Conservation & Recycling, 184, 106423. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2022.106423.