Definition

Sustainable consumption decisions at the individual and community scale will fail if humanity consumes too much of the Earth overall. We will transgress critical thresholds of planetary sustainability, beyond which lurks a future global ecology that is likely inhospitable to many species, including our own. Thus, the overconsuming nations of the world must reduce the extraction and pollution their economies cause. This is degrowth.

Degrowth is an intentional, democratic downscaling of the global economy that also creates space for the realization of social equity. It is sustainable consumption applied to the level of the whole economy (see Figure 46.1). It entails shrinking rich societies’ use of materials and energy in ways that prioritize justice and well-being for all (see Ecosocial Contract, Well-being Economy, Doughnut Economics).

History

The workers and dispossessed peoples on whose backs the global economy has grown have long criticized growth. Degrowth draws on historical resistance to the violence that economic growth requires: labor exploitation, industrial-scale extraction, and the poisoning of landscapes. But degrowth also comes from the dissatisfaction of growth’s supposed beneficiaries, who have struggled against ills of modernity such as alienation and the acceleration of the pace of life (see Work-Life Balance, Well-being and Life Satisfaction Versus Income). Even scholars famous for their ideas about how economies achieve growth have imagined worlds beyond it. In 1848, John Stuart Mill described a culturally rich, post-growth “stationary state”, while in 1932 John Maynard Keynes predicted a future where productivity increases would bring us a 15-hour work week: more leisure time rather than growing material wealth. In the 1960s and 1970s, academics and environmentalists began to warn that Earth’s limits would impose the end of growth, as critical resources like oil ran out. Half a century later, the size of the global economy – gross world product – and the total mass of materials extracted for it have both tripled, growing hand-in-hand (see Stocks Versus Flows). As the climate heats and species go extinct at one thousand times the background rate, it is now obvious that what we are running out of is not a particular resource, but the functionality of the whole Earth.

Degrowth has emerged in the 21st century as a proposal for collectively limiting ourselves, as human societies, according to the world we want to inhabit. Its recent origins lie in the French scholar-activist movement for décroissance. Rather than waiting for the planet to impose limits on growth, degrowth is about stopping economic expansion on purpose. Policy proposals for degrowth draw on the work of academics who were worried about reaching the limits to growth decades ago, such as the caps on the use of various critical resources that Herman Daly devised to maintain a steady-state economy. Today, degrowth is a diverse international movement and a familiar, if somewhat misunderstood, term to anybody who reads the news (see Social Movements).

Different Perspectives

Degrowth is not simply a matter of shrinking the economy in its current form. That would be a recession, and it would come with all the impoverishment and suffering that recessions bring. Instead, degrowth entails reorganizing society such that everybody’s basic needs can be met even as the economy contracts (see Sufficiency). As the editors of a volume on degrowth put it, “The objective is not to make an elephant leaner, but to turn an elephant into a snail” (D’Alisa et al., 2015).

The opportunity to reorganize the economy opens degrowth to myriad perspectives on economic justice, political organization, and ways of living together. A great variety of vocabularies and disciplinary backgrounds meet and mingle in the field of degrowth. Here, we summarize three complementary perspectives:

- Biophysical perspective: For the last 10,000 or so years, the Earth provided humanity and the larger community of life with rather stable living conditions. Around these, human communities patterned their social development, migrations, and rituals. The planet’s relative stability has been supported by a finite collection of biophysical resources. Humanity has overcommitted those resources to its own purposes, causing planetary instability. The sustainability literature is full of metrics for these limits, such as the nine planetary boundaries. Degrowth, then, is about steering the human ship back within the boundaries of its host. However, scholarship on degrowth acknowledges that if unsustainability is seen as simply a math problem, we can lose sight of social complexities and power relationships.

- Decolonial perspective: The colonial powers that have dominated economic decision-making and resource flows over the past several centuries have played an outsized role in our species’ takeover of the Earth. Because these powers have mismanaged things to the point of disaster, degrowth calls for both reducing their power and uplifting voices and ways of living from outside the colonial frame. Today, resources still flow overwhelmingly from South to North (see Consumption-Based Accounting). Modifying the international architecture of power through reparations and redistribution is a key goal of degrowth. The consumption of the rich, and that of rich countries, must degrow dramatically not just to make ecological space for less-developed countries to grow if they choose to, but to give the rest of the world conceptual space and control over their own resources and destinies. With this, they can define the good life as they see fit and pursue it within their means (see Buen Vivir and Buenos Convivires, Ubuntu and Food Sovereignty).

- Anti-capitalist perspective: Degrowth theorists tend to blame capitalism for the drive toward endless economic growth. The process of capital accumulation generates a continuous need for consumption growth and an ongoing pursuit of new profitable frontiers for investing the profits from previous rounds of money-making activity. In practice, this entails extending the frontiers of resource extraction and pollution. Thus, to downscale the economy in a way that can be maintained socially, it is contended that nothing less than a political transformation beyond capitalism will suffice.

Advocates of degrowth emphasize these and other perspectives to varying degrees depending on their backgrounds and affinities. A key strength of the degrowth movement – though not without its challenges – lies in its ability to bring these diverse perspectives into dialogue, fostering mutual learning and, ultimately, integration. As such, degrowth is often described as a “movement of movements” aimed at achieving global social-ecological transformation.

Application

No nation has pursued degrowth explicitly, though many have implemented policies and programs that make progress toward creating an economy that neither grows nor collapses for lack of growth. These include reducing working hours, scaling down harmful sectors like the military, and providing universal access to necessities like housing and healthcare (see Universal Basic Services, Foundational Economy).

At a smaller scale, degrowth is reflected in small-scale experimental projects and traditional societies in which people live together convivially with low levels of material consumption. From poor neighborhoods to ancient civilizations, modern ecovillages to foraging societies, people have long been practicing the art of pursuing a frugal, shared good life without growth, sometimes under the banner of degrowth but mostly not (see Eco-Communities, Alternative Consumer Cooperatives, Alternative Hedonism, Grassroots Innovation). Many seek simple and peaceful cohabitation; others are explicitly developing low-carbon or low-consumption lifestyles (see Quiet Sustainability, Voluntary Simplicity).

Certainly, initiatives for reducing the environmental impact of consumption abound, many of which are discussed in this book. Such initiatives build readiness for degrowth. Indeed, degrowth demands sustainable lifestyles for all. However, as long as governments are officially and legally committed to growth, all our well-meaning efforts will not deliver planet-saving power at a scale that matters (see Box 46.1). Degrowth is thus sustainable consumption’s willing – and inevitable – partner in pursuing just and lasting planetary health for all.

Box 46.1. Banking sustainable consumption’s savings requires degrowth

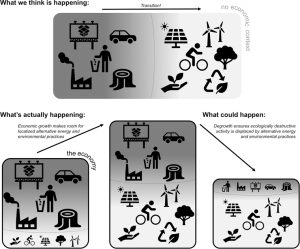

Do an image search for “sustainable future” and you will find some very predictable visions: collages of wind turbines, solar panels, and people tending to gardens, interspersed with bike lanes and rail lines; hands holding some soil and a seedling; hands holding a globe, or a globe shaped like a light bulb. Such images are meant to be both enticing and informative. The future looks greener and cleaner and also consists of a distinct set of equipment and consumption choices. The implied logic of transitioning to an ecology-compatible future is this: install alternative equipment, cultivate sustainable habits, and the transition to a sustainable future will happen.

What is hardly ever depicted in these bright green visions of a sustainability transition is the economic context. It’s easy to imply that biking instead of driving, or using solar power instead of coal, has a smaller ecological impact. However, the ecological resources saved through sustainable infrastructure and consumption decisions are not left unused; their fate is shaped by globe-spanning economic linkages, most of which prioritize economic growth. There are plenty of potential fossil fuel users lined up to claim those saved liters of gasoline. This partially explains why steady renewable energy growth has occurred alongside the growth of fossil fuels – and thus global carbon emissions. Renewables are being added to energy supplies, not replacing existing ones (see Energy Overshoot, Rebound Effects).

If we want to bank the ecological savings made possible by sustainability efforts, we’ll need to set a limit – not just on carbon (see Personal Carbon Allowance), but on economic activity itself. This will allow alternative energy and ecological practices to claim an increasing share of limited economic space. By drawing the macroeconomic border around sustainability visions, degrowth clarifies the planetary context for delivering on the ecopromises being made by dedicated communities and caring individuals across the world.

Source: John Mulrow and coauthors, 2025. Own illustration created for this publication

Further Reading

D’Alisa, G., Demaria, F., & Kallis, G. (Eds.). (2015). Degrowth: A vocabulary for a new era. London: Routledge.

Hickel, J. (2021). Less is more: How degrowth will save the world. London: Windmill.

Meadows, D.H., Meadows, D.L., Randers, J., & Behrens, W. (1972). The limits to growth: A report for the club of Rome’s project on the predicament of mankind. New York: Universe Books.

Paulson, S. (2017). Degrowth: Culture, power and change. Journal of Political Ecology, 24(1), 425–448. https://doi.org/10.2458/v24i1.20882.

Schmelzer, M., Vetter, A., & Vansintjan, A. (2022). The future is degrowth: A guide to a world beyond capitalism. New York: Verso.