Definition

The term “food miles” or “food kilometers” refers to the distance between the place where food is produced and the place where it is consumed. Food miles are measured in tonne-kilometers, representing the transport of one tonne of goods by a given transport mode (e.g., road, rail, air, sea, inland waterways, pipeline) over a distance of one kilometer. It is a proxy indicator for the environmental impact of transporting food from farm to fork. Greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions result from the dependence on fossil fuels for much of this transportation.

History

The concept of “food miles” came to the fore in 1993 when a report was published in the United Kingdom called The Food Miles Report – The dangers of long-distance food transport (Paxton, 1994). Food miles emerged to help consumers make more environmentally conscious food purchase decisions to overcome the information deficit hypothesis (see Behavior Change). It is linked with the promotion of local food by some governments, environmental groups, and agricultural and other sector organizations. The low food miles of local food are often touted as an environmental advantage (see Box 28.1). Food miles are also used in education due to its didactical properties (see Education for Sustainable Consumption). It is an easy-to-use and seemingly straightforward concept and, as such, has gained much media attention.

Box 28.1 The campaign “Local food … is miles better”

In 2006, the British agricultural business magazine Farmers Weekly started a campaign titled “Local food is miles better”. The campaign put forward seven reasons for reducing food miles. The first reason was that “food miles harm the environment”. In addition, arguments regarding freshness, security, seasonality, quality standards, transport costs, and impact on Global South countries were also mentioned.

They called on people to sign a petition urging supermarkets to stock, promote, and label locally produced food to reduce food miles and support local producers. They also ran a competition for schools, challenging 7- to 11-year-olds to design low food miles lunch boxes using seasonal and local food. David Cameron, then leader of the Conservative Party, and the secretary of state at the Department for Environment Food and Rural Affairs David Miliband (Labour), supported the campaign.

The concern represented by food miles is linked to the feeling of disconnectedness with where our food comes from (see Food Sovereignty). Distrust of the global food system and preferential feelings toward local products play a role. These feelings were fueled during the COVID-19 pandemic. Through the heuristic of “avoiding food miles”, the consumer gets a sense of gaining control over their food provisioning. Feeling more connected is also part of related initiatives and activities like the Slow Food movement and locavorism (see also Community Supported Agriculture).

Different Perspectives

The concept of food miles is presented as a measure of the environmental impact of transporting the food we consume. In addition, GHG emissions are the commonly used metric due to their dependence on fossil fuels (see Consumption-Based Accounting). However, many other factors contribute to food’s environmental impact and GHG emissions (see Protein Shift). Before reaching our plates, our food is produced (rearing and growing), stored, processed, packaged, transported, prepared, and served.

Although the concept of food miles was initially embraced as an instrument to inform consumers about the environmental impact of food, scientists have criticized the concept’s very narrow approach to such a complex issue. Today, LCA (Life Cycle Assessment) is accepted as a more robust method for estimating the environmental impact of food.

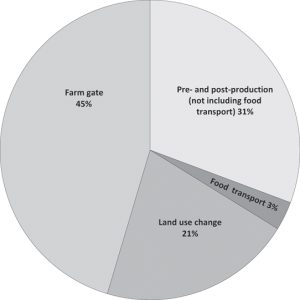

Source: Based on Sutton et al. (2024)

Food transport poses an ecological burden but this is not as great as sometimes assumed. Research shows that the share of food transportation in the total GHG emissions from food is relatively low on average (3.1%) (see Figure 28.1). There is, however, a marked difference in the share of food transport between high-income (7.1%), middle-income (3.2%), and low-income countries (0.4%).

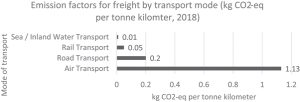

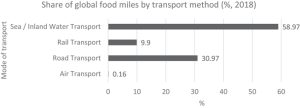

The exact GHG emissions of food transportation depend largely on the mode of transport. Air transportation has a much higher environmental impact than other modes of transport (Figure 28.2). Although food transported by air supports the use of food miles as an environmental criterion, it accounts for only 0.16% of total food miles (Figure 28.3).

In many cases, importing from regions that are better suited to cultivating particular products (more efficiently for reasons of seasonable production), as opposed to local production in greenhouses (which could require large amounts of fossil fuels), would offer greater environmental benefits. Although “fewer food miles” present an environmental benefit, without proper context, it can result in an incorrect prioritization of consumer actions (see Box 28.2). This has led commentators to suggest “first focus on what you eat (e.g., more plant-based, less food waste), not where it comes from or how it is produced” (Richie, 2020).

Source: Richie (2020) based on Poore, J., & Nemecek, T. (2018). Reducing food’s environmental impacts through producers and consumers. Science, 360(6392), 987. https://science.sciencemag.org/content/360/6392/987

Source: Richie (2020) based on Poore, J., & Nemecek, T. (2018). Reducing food’s environmental impacts through producers and consumers. Science, 360(6392), 987. https://science.sciencemag.org/content/360/6392/987

Box 28.2 Consumers’ perspectives on “food miles” and “buying local”

Although other mitigation options have greater potential to reduce environmental impact, “reducing food miles” or “buying more locally sourced food” are at the top of the list for consumers. When EU consumers were asked in 2019 what actions they have taken in the past six months to protect the environment, almost half (42%) of the respondents “bought local products”, the third most popular option. When asked which is the most important characteristic of sustainable food, almost a quarter of the respondents answered “local and short supply chains”. Eating locally produced food is also associated with a healthier diet, less packaging, sustainable agriculture, less food waste, and support of the local economy. These associations can be true and explained by the “home country bias” but are not necessarily so in practice.

Food miles are relevant in light of other sustainability aspects. Reducing food miles often involves buying more locally sourced products and supporting local producers and their livelihoods. This may require paying a premium price. The benefits will likely be larger if coupled with shorter supply chains, which could mean more economic power for a smaller number of participants in the food chain. From a consumer point of view, this can also result in a stronger sense of connection and appreciation for these local producers.

Inevitably, some food products must be imported because they cannot be cultivated in the region of consumption. In some parts of the world, production possibilities are limited. Researchers also highlight the importance of food trade for global food security. International trade is considered a key component of climate change adaptation. An interconnected food system, which connects local, regional, and global food systems, may be preferable in terms of food security and resilience.

Applications

Numerous (online) self-help guides promote food miles as a selection criterion to lower the environmental impact of food purchases. Periodically, media outlets emphasize this message in lifestyle articles. In reports or online resources, you can find examples of product food miles being compared.

When communicating a product’s environmental performance, transport is included in calculating an ecoscore or level of GHG emissions. However, there are few examples of supermarkets directly informing consumers about food miles. While some attempts at environmental labeling highlight food miles, these efforts have resulted in prototype concepts rather than widespread adoption (see Ecolabeling).

The label “local” is often used in general communication and retail but is not always substantiated. Moreover, “local” can have shifting meanings depending on how far away a product may be produced and the consumers’ perception. Checking the country of origin is put forward as a tool to estimate food miles.

Some examples indicate the mode of transport in food retailing. Products transported by air can carry the label “by air”, sometimes in combination with a “” or “carbon” notation or red color. However, research has shown that this can backfire, as it might be perceived as “fresh”, “high quality”, or “high end” and thus be more appealing to consumers.

Better examples can be found in, among others, the Netherlands, Sweden, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, and Ireland where in the early 2020s several supermarkets and food service companies announced they would stop importing food products by air. This can be considered an action to reduce food miles while also delivering great environmental benefits.

Although food miles as an environmental sustainability concept is contested, it is still being used in communication by industry, NGOs, and popular media when discussing sustainable food consumption. Given the limited cognitive space available for the consumer to consider factors when making food decisions (see Choice Paralysis), messages on food miles can add to confusion and distortion around environmentally motivated priorities when purchasing food.

Further Reading

Janssens, C., Havlík, P., Krisztin, T., Baker, J., Frank, S., Hasegawa, T., Leclère, D., Ohrel, S., Ragnauth, S., Schmid, E., Valin, H., Van Lipzig, N., & Maertens, M. (2021). International trade is a key component of climate change adaptation. Nature Climate Change, 11, 915–916. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-021-01201-8.

Paxton, A. (1994). The food miles report – the dangers of long distance food transport. London: Sustainable Agriculture, Food and Environment (SAFE) Alliance.

Richie, H. (2020). You want to reduce the carbon footprint of your food? Focus on what you eat, not whether your food is local. Our World in Data. Available at: https://ourworldindata.org/food-choice-vs-eating-local (accessed: 14 May 2024).

Stein, A.J., Santini, F. (2021). The sustainability of “local” food: A review for policy-makers. Review of Agricultural, Food and Environmental Studies, 103, 77–89. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41130-021-00148-w.

Sutton, W.R., Lotsch, A., Prasann, A. (2024). Recipe for a liveable planet – Achieving net zero emissions in the agrifood system. In Agriculture and food series. Washington, DC: World Bank Group. Available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10986/41468 (accessed: 1 January 2025).