Definition

Money can be broadly defined as anything that is widely accepted as a medium of exchange, a unit of account, and a store of value. It can be used to buy goods and services, measure their value, and retain value over time.

Money also facilitates consumption. People can satisfy their immediate needs, for instance, by borrowing money. When an individual spends less than they earn, they save money. Savings can then be used for future consumption or to buy financial assets like stocks. In everyday language, buying stocks or bonds is often called investment, but in economics, investment means spending on capital goods like machinery or buildings (see Sustainable Finance).

In the current system, most of the money supply is made up of bank-issued money, which is created through the lending process. This process is regulated by the state and the central bank. When a bank grants a loan, it credits the borrower’s account with a deposit, effectively creating new money. Most of the money in the economy is created this way, rather than being issued by central banks.

Money fundamentally shapes sustainable consumption and lifestyles by influencing consumer behavior, driving resource allocation and market demands, and perpetuating unsustainable growth. It can thus both catalyze and hamper sustainability transitions through financial (dis)incentives and distribution logic and mechanisms.

History

Before barter systems, small communities relied on reciprocity and social bonds. In societies where everyone knew each other, trust was inherent, and exchanges were based on mutual aid and social obligations. As communities grew and trade between strangers increased, barter systems, where goods and services were directly exchanged, developed. To further facilitate trade, especially in larger and more complex economies, popular commodities such as grain, livestock, and eventually metal coins were used as mediums of exchange.

The introduction of paper money added another layer of trust, now dependent on state authority, and brought new features to money, including easier transport and storage. In the 20th century, the use of credit cards revolutionized transactions, allowing for faster global exchanges and enabling consumers to increasingly spread their spending over time. Later, with the expansion of online shops, micro-financing allowed consumers to buy immediately and pay later in installments. Gradually, the government allowed the role of banks to become more prominent, and the share of money legally issued by central banks considerably decreased relative to the money created by banks through their lending activities.

Source: Adapted from Jouzi et al. (2024)

The concept of money as a store of wealth differs fundamentally from traditional forms of wealth. Traditional wealth has intrinsic value but can depreciate over time due to changes in owner preferences, wear and tear, and technological advancements. As an abstract representation of wealth within a monetary system, money does not suffer from obsolescence. However, the modern monetary system introduced the potential for inflation, which directly affects the purchasing power of each unit of currency and the consumption behavior of individuals.

Over time, money has gained various other social functions (see Box 38.1). It influences decision-making at multiple levels: individuals decide whether to purchase products and services, corporations evaluate costs and profits in a competitive market, and authorities plan policies to achieve environmental, social, and economic goals within their budget constraints. The economic system has become the foundation for most societal interactions, increasingly defined by monetary values. In modern societies, salary and income are often seen as measures of individual success, while businesses focus on maximizing profit, and states assess their performance based on measurable economic growth.

Box 38.1 Money-consumption interconnections

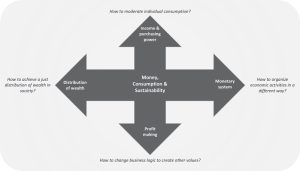

The relationship between money, consumption, and sustainability is complex and multifaceted. Consumption and production are interdependent processes in the economic system. At the business level, companies are obliged to make profits by producing goods and services. At the societal level, the just distribution of wealth is an ideal of strong sustainability, which contrasts with the competitive structure of the current system. Although at the individual level, money is linked to consumption as purchasing power, the interconnection of money and consumption cannot be understood without considering their embeddedness within the greater context of the socio-economic system.

Since the early 20th century, when environmental crises were not as prominent as they are today, scholars have highlighted the troubling role of money as an institution in society and critically discussed it. By the mid- to late 20th century, scholars and advocates examined the consequent crises of the monetary system, advocating for alternative forms of money. More recently, terms like “sustainable finance” have appeared in monetary discussions, aiming to address critics and promote environmental, social, and financial stability.

Different Perspectives

There is inconsistency in the approaches to using money for implementing strategies aimed at sustainable consumption (see Figure 38.1). These perspectives can be grouped into three categories.

In the first perspective, monetary intervention plays a key role in adjusting consumption habits. These solutions fall within the current monetary system and include adjusting prices and taxes in favor of sustainable choices for consumption and investing the extra money to financially support sustainable innovations. Investing in different aspects of sustainability is a common tactic in this viewpoint. At the individual level, this perspective supports decoupling consumption from income (see Well-being and Life Satisfaction Versus Income, Household Income Versus Carbon Footprint).

The second perspective is revolutionary and criticizes the current monetary system, often suggesting solutions based on avoiding money. Unlike the first viewpoint, monetary intervention is only accepted as a short-term solution and is not seen as effective enough to compensate for the harms caused by overproduction and overconsumption. This view emphasizes promoting non-monetary values and social activities, avoiding markets, and encouraging unpaid work.

The third perspective is a reformist view that calls for restructuring the monetary system while retaining the concept of money as the medium of transaction. This perspective includes reducing the size of the financial system, as seen in local economies, and using local and other alternative currencies. Alternative currencies are forms of money that exist outside of traditional government-issued currencies. Cryptocurrency is a virtual form of currency that allows for transactions over the internet, with Bitcoin being the most well-known example. Two other examples of alternative currencies are those backed by carbon credits to represent a reduction in greenhouse gas emissions, and time-based currencies where hours of labor are the exchange medium.

Economic growth generates money to repay loans, driven by interest, which harms the environment through increased waste and resource use. Proponents of decoupling believe emissions can be separated from growth, aligning with ecological modernization. Opponents argue that continuous growth leads to ever-increasing production and consumption (see Degrowth). Lowering consumption challenges growth expectations and the role of money (see Sufficiency, Steady-State Economy and Foundational Economy). Proposed solutions like green growth, the circular economy, and green consumerism have proven slow, ineffective, and insufficient to keep human activities within the planet’s carrying capacity (see Doughnut Economics)

Application

Monetary intervention: At the state level, adjusting taxes and subsidies to control emission levels and promote sustainable consumption is a common solution. Proponents of decoupling suggest using the extra revenue from taxing environmentally harmful activities or products to support sustainable investments and innovations through grants and funds, or to make sustainable choices more affordable by adjusting prices. This includes the idea of life cycle pricing for products and campaigns to avoid cheap products that do not reflect their true costs. Other proposed monetary interventions include guaranteed income and unconditional basic income for all, with the goal of fair wealth distribution and social equality (see Universal Basic Services). The revolutionary perspective acknowledges the necessity of these actions only as temporary measures. It highlights the shortcomings of solutions involving monetary transactions and promotes solutions that are independent of money.

Behavior-income dependency: The wealthiest 25% of the global population is responsible for 74% of excess energy and material consumption. Increased income leads to larger living spaces, more air travel, and luxury goods, contributing to higher emissions and waste. While some argue that affluent individuals and high-income celebrities can promote sustainable behaviors, it is undeniable that investment is a primary income source for affluent individuals. This reliance on investment may cause resistance to post-growth solutions, thereby hindering changes in traditional business practices and the current economic system.

Money rebound effect: In the context of money-consumption dependency, the rebound effect of money refers to unintended increases in consumption from reduced consumption elsewhere. For instance, if affluent groups reduce consumption, prices may drop, leading to increased consumption by lower-income groups. This shift between groups of consumers can be justified by equality aims in sustainable societies. Supporters of the monetary intervention perspective debate if revenue from consumption or income taxes will increase consumption elsewhere unless the saved money or tax income is invested in sustainable practices and investments.

Income-well-being opposition: Many sacrifice well-being for money, working excessively, and missing family time. Reducing working hours is a practical solution, but it needs support from other social, cultural, and economic initiatives, due to the current system’s emphasis on monetary values. Social ecological economists advocate restructuring economic activities to focus on meeting society’s needs and provisioning, rather than monetary evaluation (see Ecological Economics). In such a system, individual life or a successful business is not dependent merely on salary and profit.

Further Reading

Alcott, B. (2008). The sufficiency strategy: Would rich-world frugality lower environmental impact? Ecological Economics, 64, 770–786. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2007.04.015.

Core Economy. (2017). The economy (eBook). Unit 10: Banks, money, and the credit market. Available at: https://www.core-econ.org/the-economy/book/text/10.html (accessed: 29 October 2024).

Jouzi, F., Levänen, J., Mikkilä, M., & Linnanen, L. (2024). To spend or to avoid? A critical review on the role of money in aiming for sufficiency. Ecological Economics, 220. Elsevier B.V. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2024.108190.

Nielsen, K.S., Nicholas, K.A., Creutzig, F., Dietz, T., & Stern, P.C. (2021). The role of high-socioeconomic-status people in locking in or rapidly reducing energy-driven greenhouse gas emissions. Nature Energy, 6, 1011–1016. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41560-021-00900-y.

Read, R. (2009). Towards a green philosophy of money. In L. Leonard & J. Barry (Eds.), Special edition: Financial crisis – environmental crisis: What is the link? Advances in ecopolitics, Vol. 3, pp. 3–26. Leeds: Emerald Group Publishing Limited. https://doi.org/10.1108/S2041.