Definition

Moral licensing, also known as self-licensing, occurs when previous virtuous or moral behaviors make individuals feel entitled to act in a way they would not permit themselves otherwise. This sense of entitlement to engage in behaviors normally considered unethical is a psychological mechanism that arises when individuals’ prior virtuous actions enhance their self-image, making them feel good about themselves. As a result, individuals allow themselves to act in a less virtuous way without feeling guilty or compromising their image as a moral person. When pro-environmental behavior is seen as a virtuous act, it can lead to moral licensing in subsequent decisions.

Moral licensing involves a sequence of two behaviors: a good deed followed by a bad or less good action in the opposite direction. This balancing behavior makes moral licensing a particular case of “negative behavioral spillover”. The umbrella term “behavioral spillover” is used when one action influences another, either positively – further promoting the first action – or negatively – permitting oneself to deviate from the first action (see Table 22.1).

When it comes to sustainable consumption, after making a seemingly environmentally conscious purchase (e.g., buying an electric car), individuals may feel justified in making less sustainable choices later, such as indulging in excessive consumption (e.g., having more than one car) or engaging in wasteful practices (e.g., driving the car more often). For example, as illustrated in the moral licensing scenario in Table 22.1, a person who decides to take the train instead of flying may feel proud of their sustainable choice. This pride can enhance her moral self-conception and create a sense of entitlement, potentially leading them to justify subsequent unsustainable behaviors, such as using more heating than they typically would if they had not made the prior sustainable choice.

History

The concept of moral licensing originated in social psychology and was devised by Monin and Miller (2001) as part of their research on prejudice against people of color. Their experiments demonstrated that people are more willing to express prejudiced attitudes when their past behavior has established them (in their own eyes) as moral, unbiased individuals. Monin and Miller’s findings challenged the prevailing assumption that moral consistency is ubiquitous. Previously, the social psychology literature held that people show consistent behavior – leading to positive behavioral spillovers – to avoid cognitive dissonance (i.e., the mental discomfort experienced when present actions do not align with past actions).

Despite originating in social psychology, the concept of moral licensing has spread to other fields, including consumer choice and marketing. These fields had already considered that initial pro-environmental actions might lead to neglecting further efforts, borrowing terms from economics like the rebound effect (i.e., increased consumption following efficiency improvements) or providing other psychological explanations like the single action bias (i.e., thinking a single corrective action sufficiently reduces risks, preventing future action). Moral licensing complemented these perspectives as a particular case of negative behavioral spillover.

| Behavior 2 (Heating) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Behavior 1 (Transport) | (+) Mindful use of heating | (-) Excessive use of heating | |

| (+) Train | (+) (+) Moral consistencyI’ve taken a train instead of flying, let’s keep up the good work and not turn the heating up too much | (+) (-) Moral licensingI’ve avoided taking a flight today, I deserve to turn the heating up a bit more | |

| (-) Flight | (-) (+) Moral cleansingI’ve already polluted a lot today through flying, best not to turn the heating up too much when arriving home | (-) (-) Moral consistencyI’ve already polluted a lot today, so what does it matter if I turn the heating up a bit more | |

Research has shown that moral licensing is not always a within-domain phenomenon: an initial pro-environmental behavior can affect a future action in an unrelated area, and vice versa. For example, in a virtual shopping experiment, participants who bought ecofriendly products were later greedier in an unrelated money-sharing task and more likely to steal money compared to those who bought regular products (Mazar & Zhong, 2010). Moreover, recent research showed that merely reflecting on past climate-friendly actions can justify unsustainable choices in the present. For example, in one experiment, participants who had abstained from flying in the past two years felt less guilty about their meat consumption when reminded of their prior sustainable behavior before – rather than after – being asked about meat consumption.

Different Perspectives

Meta-analytic evidence shows that the moral licensing effect is small to medium in size, slightly below the average effect size in social psychology. Whether this effect impacts a majority of people who have performed previous good deeds or remains a marginal phenomenon largely depends on framing and behavioral ambiguity.

Moral licensing occurs because people tend to pursue multiple, sometimes conflicting goals (e.g., trying to eat more organic food, while also trying to save money on groceries). The framing of past actions can either justify pursuing conflicting goals or reinforce consistent behavior toward a goal. For example, the initial behavior of buying organic food due to a personal commitment to eating sustainably is less likely to lead to moral licensing than buying organic food just because there was a convenient discount at the supermarket. Influencing the level of abstraction is what makes framing effective: thinking concretely about past moral behavior (e.g., “I take the time to compost my food waste”) focuses attention on the act itself, making moral licensing more likely, while thinking abstractly about the same action (e.g., focusing on the pro-environmental values that inspired the action) leads to more consistent behavior.

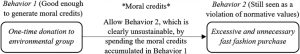

Apart from framing, licensing effects also depend on the extent to which behaviors appear superficial or guided by normative values (see Social Norms). Superficial initial behaviors, like bringing a reusable bag to the supermarket, have low diagnosticity – meaning they reveal little about an individual’s environmental commitment. As a result, superficial initial behaviors might not establish an individual’s morality, preventing them from feeling licensed to transgress in future behaviors. Conversely, behaviors that seem to be motivated by personal values facilitate moral licensing by reducing suspicion of immorality. Investigating this behavioral ambiguity has led researchers to wonder whether initial pro-environmental behavior serves to reinterpret future negative actions (“moral credentials”) or simply to counterbalance them (“moral credits”) (see Box 22.1).

Box 22.1 Two models of moral licensing from the observer’s perspective

Moral credits

This model posits that individuals accumulate moral credits (as in a moral bank account) from past actions to justify subsequent negative behavior; maintaining an overall positive moral balance. The moral “license” is thus a form of capital or credit acquired in a previous behavior used in subsequent behaviors. Under a moral credits model, the licensed behavior is unmistakably bad and the individual’s behavior will be interpreted as inconsistent. For example:

https://vocabulary.hotorcool.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/12/78f706f7-1cf4-4aa1-be44-45d85d5dc252-100x18.jpeg 100w, https://vocabulary.hotorcool.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/12/78f706f7-1cf4-4aa1-be44-45d85d5dc252-340x61.jpeg 340w, https://vocabulary.hotorcool.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/12/78f706f7-1cf4-4aa1-be44-45d85d5dc252-480x86.jpeg 480w, https://vocabulary.hotorcool.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/12/78f706f7-1cf4-4aa1-be44-45d85d5dc252-674x121.jpeg 674w, https://vocabulary.hotorcool.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/12/78f706f7-1cf4-4aa1-be44-45d85d5dc252-200x36.jpeg 200w, https://vocabulary.hotorcool.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/12/78f706f7-1cf4-4aa1-be44-45d85d5dc252.jpeg 749w" sizes="auto, (max-width: 300px) 100vw, 300px">

https://vocabulary.hotorcool.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/12/78f706f7-1cf4-4aa1-be44-45d85d5dc252-100x18.jpeg 100w, https://vocabulary.hotorcool.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/12/78f706f7-1cf4-4aa1-be44-45d85d5dc252-340x61.jpeg 340w, https://vocabulary.hotorcool.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/12/78f706f7-1cf4-4aa1-be44-45d85d5dc252-480x86.jpeg 480w, https://vocabulary.hotorcool.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/12/78f706f7-1cf4-4aa1-be44-45d85d5dc252-674x121.jpeg 674w, https://vocabulary.hotorcool.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/12/78f706f7-1cf4-4aa1-be44-45d85d5dc252-200x36.jpeg 200w, https://vocabulary.hotorcool.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/12/78f706f7-1cf4-4aa1-be44-45d85d5dc252.jpeg 749w" sizes="auto, (max-width: 300px) 100vw, 300px">

Moral credentials

This model suggests that the initial moral act influences how subsequent behavior is interpreted. The moral credentials model is a plausible explanation in situations where the licensed behavior is superficial and the initial behavior is unmistakably good. This casts doubt on whether the second behavior is immoral at all, considering the person’s track record. Under the credentials model, the morality of the licensed behavior is unclear, and without more information, individuals’ behavior might still be interpreted as consistent. For example:

https://vocabulary.hotorcool.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/12/83d70374-2ff4-40cc-8465-ee2baaeaed28-100x18.jpeg 100w, https://vocabulary.hotorcool.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/12/83d70374-2ff4-40cc-8465-ee2baaeaed28-340x63.jpeg 340w, https://vocabulary.hotorcool.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/12/83d70374-2ff4-40cc-8465-ee2baaeaed28-480x88.jpeg 480w, https://vocabulary.hotorcool.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/12/83d70374-2ff4-40cc-8465-ee2baaeaed28-674x124.jpeg 674w, https://vocabulary.hotorcool.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/12/83d70374-2ff4-40cc-8465-ee2baaeaed28-200x37.jpeg 200w, https://vocabulary.hotorcool.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/12/83d70374-2ff4-40cc-8465-ee2baaeaed28.jpeg 760w" sizes="auto, (max-width: 300px) 100vw, 300px">

https://vocabulary.hotorcool.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/12/83d70374-2ff4-40cc-8465-ee2baaeaed28-100x18.jpeg 100w, https://vocabulary.hotorcool.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/12/83d70374-2ff4-40cc-8465-ee2baaeaed28-340x63.jpeg 340w, https://vocabulary.hotorcool.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/12/83d70374-2ff4-40cc-8465-ee2baaeaed28-480x88.jpeg 480w, https://vocabulary.hotorcool.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/12/83d70374-2ff4-40cc-8465-ee2baaeaed28-674x124.jpeg 674w, https://vocabulary.hotorcool.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/12/83d70374-2ff4-40cc-8465-ee2baaeaed28-200x37.jpeg 200w, https://vocabulary.hotorcool.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/12/83d70374-2ff4-40cc-8465-ee2baaeaed28.jpeg 760w" sizes="auto, (max-width: 300px) 100vw, 300px">

Application

The behavioral inconsistency caused by moral licensing widens the gap between pro-environmental attitudes and actual behaviors (see Attitude-Behavior Gap). Shaming is a common tactic to encourage behavior change by inducing guilt for not conforming to a social norm. However, this can lead people to choose behaviors that minimize guilt with the least effort (e.g., purchasing carbon offsets) rather than undertaking more effective actions (e.g., avoiding flying). Moral licensing can exacerbate green consumerism by making individuals feel justified in skipping sufficiency behaviors after performing easier, efficient behaviors that reduce their guilt and make them feel morally allowed to maintain their consumption levels.

From a policymaking perspective, while guilt can be a powerful motivator, trying to leverage consumers’ self-image tends to backfire (see Box 22.2). Consumers need a choice architecture that encourages behavioral consistency without exploiting guilt (see Choice Editing). Once people start making sustainable choices out of personal responsibility, moral licensing can be avoided by emphasizing the ongoing nature of their environmental commitment rather than viewing individual actions as isolated accomplishments.

Box 22.2 Three pro-environmental interventions that resulted in moral licensing

Weekly feedback on water consumption → More electricity consumption

In a field experiment in 154 apartments, Tiefenbeck et al. (2013) found that taking part in a water conservation campaign reduced residents’ water usage, but also increased their electricity consumption. The researchers concluded that the water conservation campaign may have made people feel they had already done their part for the environment, leading them to be less careful about electricity usage.

Salient carbon taxes → Increased demand for taxed products

In a series of survey experiments, participants knowingly paying a carbon tax felt less guilty about their prospective purchases, and more licensed to consume carbon-intensive products. In this study, Hartmann et al. (2023) showed that salient carbon taxes indicated as part of the product price were less effective in curbing demand than hidden ones – even though the price increase was the same in both cases.

Promote ecolabeled products → Stick to resource-intensive activities

Data from EU-27 countries shows that ecolabeling is linked to higher (rather than lower) resource consumption. Survey data from the United Kingdom also indicates that a willingness to pay for ecolabeled products is linked with increased resource use. Based on these two interrelated studies, Barkemeyer et al. (2023) concluded that consumers might use the purchase of ecolabeled items to morally justify continuing other resource-intensive activities, rather than as a first step toward genuine behavior change. For wealthy consumers, buying ecolabeled products is a more convenient and simpler pro-environmental action than making significant lifestyle changes. Consequently, overly promoting ecolabeled products can be risky, as wealthy consumers may wrongly perceive them as guilt-reducing items, ultimately increasing their overall environmental impact.

Overall, pro-environmental interventions are less likely to lead to moral licensing when individuals think abstractly, focusing on their ongoing commitment rather than on the result of a specific action. Interventions that strengthen environmental self-identity are particularly effective, as individuals who strongly identify with a cause are less likely to exhibit moral licensing. Therefore, to avoid licensing, interventions should encourage individuals to reflect on how their actions align with their values, assess the extent of their pre-existing identification with those values, and find ways to enhance this connection (see e.g., Education for Sustainable Consumption).

Further Reading

Barkemeyer, R., Young, C.W., Chintakayala, P.K., & Owen, A. (2023). Eco-labels, conspicuous conservation, and moral licensing: An indirect behavioural rebound effect. Ecological Economics, 204, 107649. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2022.107649.

Hartmann, P., Marcos, A., & Barrutia, J.M. (2023). Carbon tax salience counteracts price effects through moral licensing. Global Environmental Change, 78, 102635. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2023.102635.

Mazar, N., & Zhong, C.B. (2010). Do green products make us better people? Psychological Science, 21(4), 494–498. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797610363538.

Monin, B., & Miller, D. T. (2001). Moral credentials and the expression of prejudice. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 81(1), 33.

Tiefenbeck, V., Staake, T., Roth, K., & Sachs, O. (2013). For better or for worse? Empirical evidence of moral licensing in a behavioral energy conservation campaign. Energy Policy, 57, 160–171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2013.01.021.