Definition

The business literature has shown that in many markets, products from competing producers perform equally well. In such cases, the basis of competition has shifted from functional performance to price, which in turn reduces profit margins. Enhancing production volumes then becomes the only way to enhance overall profits. The result is that in many markets we have seen a shift toward “fastness” and “planned obsolescence”. Fast fashion, fast furniture, and so on, incentivize consumers to buy new stuff that fits the newest fashion before old products are worn out.

Another manifestation of such product-oriented business models is that products are not repairable or reusable by design, even when a minor component fails (see Repair and Ecodesign). A washing machine with a failing ball bearing will see labor costs for repairs as high as the costs of a new machine. A breakdown of a key on a computer requires replacing the entire keyboard or even the computer.

From a sustainable consumption perspective, product-service systems (PSS) form an interesting alternative to such product-oriented business models. PSS aim to satisfy user needs by providing an integrated service, in the form of a unit of product use or a desired result sought from the product. The user pays for the result or unit of use. Any product used in the PSS is owned, serviced, and maintained by the provider (Box 70.1; also see Extended Producer Responsibility).

With the profit center now located in service provision instead of product sales, providers have an incentive to minimize the life-cycle costs of the product-service. It is in their interest to have products that are sturdier, easier to repair, and, if the provider also takes responsibility for consumables in the use phase, that products are energy efficient (see The Role of Business). In theory, PSS thus creates a win-win: lowering the overall life cycle costs of achieving the product’s functionality, which can be shared by both users and providers, and lowering environmental impacts. PSS can also enhance the competitiveness of providers by meeting clients’ needs in an integrated and customized way; building unique relationships with clients and engendering their loyalty; and allowing providers to innovate faster by being able to easily monitor clients’ needs.

Box 70.1 Some illustrations of the success and failure of PSS

- Industrial electric engines. Around the year 2000, a major European industrial electric engine producer faced competition from Asian companies. The former’s engines were higher priced, but much more energy efficient, and so had lower costs per use-hour. They developed a result-oriented business model: install a motor, pay the electricity bill, and price per hour of use. They immediately ran into purchasing mandate issues. Engines were paid for from a central investment budget, and electricity from an operational budget. The provider further took the risk of rising electricity prices. Once the contract was closed, the provider inevitably faced a loss when electricity prices rose.

- Copiers. Major copier producers don’t sell their copiers anymore, but let users pay per print. The copier is remotely monitored, giving excellent insight into user behavior. When signs of malfunctioning are seen, the copier is replaced. Many old parts are used in the next generation of copiers, saving significant costs.

- Car sharing. Car-sharing systems lower transport emissions, since people tend to use public transport more often and use cars with more passengers (see e.g., Amatuni et al., 2020). However, so far, car sharing has remained a niche market in many places. Access to the car is more difficult, for instance, while car sharing lacks the prestige of car ownership.

- Car hailing. Car-hailing platforms like Uber and Didi became very successful competitors of regular taxi services. They give access to a car in minutes, offer easy and secure electronic payment, and are relatively cheap (sometimes for questionable reasons, such as taxes or labor being underpaid).

- Communal washing services. The above four examples focus on business-oriented PSS since most products in modern society are provided via markets. PSS work well in other contexts, however. In Sweden, common washing machines in multifamily residential buildings are the norm, included in a service package of the housing association.

History

Already in the 1980s, Walter Stahel proposed business models that sell the service or performance of the product instead of the product as such, as a method to lower resource use and emissions related to final consumption. This concept was further elaborated between 2000 and 2010 by authors such as Oksana Mont, Tim Baines, and Arnold Tukker, and more recently by Nancy Bocken. In parallel, various industries started to experiment with PSS business models, with varying levels of success.

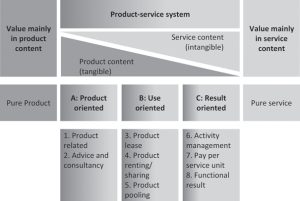

These academic and practical experiences led to a now fairly generally accepted typology of PSS in three broad classes, as illustrated in Figure 70.1. Product-oriented services are geared toward sales of products, but some extra services are added. In use-oriented services, the traditional product plays a central role but it is owned by the provider and made available for use in different forms, and sometimes shared by several users. In result-oriented services, the client and provider agree on the result, and there is no predetermined product involved.

The use-oriented and result-oriented services are the most promising ones ecologically because the provider is in general incentivized to reduce the cost of the services by reducing resource use and prolonging the life of the product and its components.

Different Perspectives

The examples in Box 70.1 have shown that use- and result-oriented services indeed can be successful and can lead to lower environmental impacts. But we also see that many PSS stay in niche markets due to various problems inherent to the business model.

Source: Tukker, Tischner (eds.), New business in old Europe, Greenleaf Publishers (2006)

First, the market value of the product-service can be lower than ownership of the product. While the functionality of car sharing and owning a car may be similar, the intangible value of car ownership gives the latter an advantage. Also, access to a car in car sharing is not as instantaneous as when it is owned.

Second, the life cycle costs of the product-service may be higher. This is because a provider takes responsibility for the use stage of a product. In the case of car sharing and pooling, the provider must factor in drivers who treat the car with less respect since they do not own it. While some protection against such misbehavior can be arranged via legal agreements, the transaction costs of such enforcement and lawsuits can become very expensive.

Further, in the case of product sales the full costs of the product are recovered directly. In the case of pay-per-use, this only happens over the lifetime of the product, implying a producer has much higher upfront investment and capital needs, which it needs to obtain from a bank that may not understand this new business model. Finally, product-service systems need a whole business model overhaul of the provider, for example, toward now also offering repair services. It may be that the provider currently has other core competencies and needs to invest heavily to make the new business model work.

Applications

In principle, use- and result-oriented PSS have the potential to create systems of provision that give both producers and consumers incentives to counter the unsustainable practices of planned obsolescence, fast change of fashion, and providing products that are by design not repairable or reusable. By offering users a result of having them pay per unit of use, the source of a service becomes the profit center. What then determines profit is providing a service with minimal life cycle costs – hence minimal use of resources.

As shown in Box 70.1, in the past, various attempts have been made to put PSS on the market. Some were successful, others were not. We see that owning a product has many advantages: prestige (see Conspicuous/Positional Consumption), control over the use of the product, and so on. Offering a PSS implies also solving many hitherto irrelevant problems: taking responsibility for the use stage, dealing with higher upfront capital needs, and higher transaction costs in general. For these reasons, particularly in Business-to-Consumer (B2C) contexts, PSS tend to stay in niches. Exceptions are platform services like Uber and Airbnb. They use existing capital assets and hence are cheaper than a traditional provider and/or offer more convenient access to the service. Yet, these platforms have many disadvantages. They are so powerful that they extract excessive value, marginalizing the income of providers. There are unwanted side effects, such as houses in popular places disappearing from the rental market or drivers not being drivers protected by labor laws.

PSS have more success in a Business-to-Business (B2B) context, although they are still not mainstream. Mature products with standardized components, used in a predictable environment that can be easily repaired or the components that can be easily used in the next product generation, are good candidates to build a PSS business model around.

One has to, however, consider that PSS is nothing more or less than a business model that has to be successful in the current societal and business environment. This is a system that is unstable without GDP growth. PSS will, therefore, never be the ultimate answer to broader questions around how to create a degrowth or well-being economy (see Degrowth and Well-being Economy) – these imply a radical change to the rules of our economic game.

Further Reading

Amatuni, L., Ottelin, J., Steubing, B., & Mogollón, J.M. (2020). Does car sharing reduce greenhouse gas emissions? Assessing the modal shift and lifetime shift rebound effects from a life cycle perspective. Journal of Cleaner Production, 266. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.121869.

Bocken, N.M.P., de Pauw, I., Bakker, C., & van der Grinten, B. (2016). Product design and business model strategies for a circular economy. Journal of Industrial and Production Engineering, 33(5), 308–320. https://doi.org/10.1080/21681015.2016.1172124.

Mont, O., & Tukker, A. (2006). Product-service systems: Reviewing achievements and refining the research agenda. Journal of Cleaner Production, 14(17), 1451–1454. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2006.01.017.

Stahel, W.R. (2016). The circular economy. Nature, 531(7595), 435–438. https://doi.org/10.1038/531435a.

Tukker, A. (2015). Product services for a resource-efficient and circular economy – A review. Journal of Cleaner Production, 97, 76–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2013.11.049.