Definition

Voluntary simplicity (VS) is a lifestyle characterized by intentionally reducing material consumption, making a conscious effort to live a balanced life, practicing frugality, and cultivating non-materialistic sources of well-being, life satisfaction, and personal growth. The decision to live a simple life may stem from a realization of the unsustainability of overconsumption for both individuals and the planet, feeling disillusioned with materialism and excessive ownership of possessions, and/or wanting to dedicate time and resources to more meaningful and fulfilling activities.

The concept was described by Elgin and Mitchell (1977) as a way of life guided by five core values: material simplicity (frugal consumption; see Sufficiency), human scale (a desire for a more human sense of proportion), self-determination (a desire to achieve greater control over one’s life), ecological awareness (recognition of the interdependence of people and other species), and personal growth (a desire to explore and develop the inner life).

This lifestyle often involves reducing working hours, which is linked to living a balanced life and a desire to break the “earn and spend” cycle (see Hedonic Treadmill, Work-Life Balance). Voluntary simplifiers may choose to reduce their hours of paid work to create more free time and find purpose through meaningful activities for themselves and others. There are various trajectories that individuals may take in pursuing a VS lifestyle and different levels of engagement, with some people partially adopting this lifestyle by embracing some practices, and others fully transforming their lives.

Importantly, achieving a simple lifestyle involves more than just cutting back on consumption; it necessitates a deliberate dedication to simplicity. What sets this lifestyle apart is its voluntary nature. Hence, it is important to distinguish between voluntary simplicity and reduced consumption as a response to poverty, limited resources, or due to the requirement of an external authority.

History

Throughout history, many individuals and groups have embraced the idea of living a simpler yet more fulfilling life. The central concepts of intentionally simplifying one’s life can be traced back to the teachings of ancient Greek and Chinese philosophers. Henry David Thoreau, who chose to leave his town to live alone in the woods, is a prominent advocate for this philosophy. His book, Walden, reflects on the virtues of simple living in nature. In the United States, Thoreau’s birthday on July 12 is informally celebrated by voluntary simplifiers as National Simplicity Day.

However, the concept was formally conceptualized by Gregg (1936/2009) as an “inner and outer condition”, which entails “singleness of purpose, sincerity, and honesty within, as well as avoidance of exterior clutter, of many possessions irrelevant to the chief purpose of life” (p. 4). For Gregg, this means “an ordering and guiding of our energy and our desires, a partial restraint in some directions” to achieve “greater abundance” in others.

In recent years, VS has received growing attention in mass media, marketing, and academic discourse. An example is the emergence of social media communities where consumers search for inspiration from like-minded consumers (Table 15.1). Other resources are available on YouTube or websites such as The Simplicity Institute, which aims to foster dialogue on the necessity of shifting from growth-driven, consumer-focused societies, or The Simplicity Collective.

Different Perspectives

Despite being rooted in environmental and social responsibility concerns, VS arguably embraces broader ethical considerations than those traditionally associated with sustainable consumption. Adopting a simpler lifestyle promotes ecological well-being and is closely linked to values such as moderation, thrift, and wisdom, facilitating the practice of justice, generosity, and other virtues (see Values and Consumption). Research in psychology and marketing has suggested that traits such as consumer impulsiveness and materialism negatively impact practicing VS, while mindfulness, satisfaction with life, and self-efficacy positively impact VS.

Several related constructs may partially overlap with voluntary simplicity as expressions of conscious consumption, including downshifting, mindful consumption, minimalism, frugality, and anti-consumption. Downshifting involves choosing to reduce income and consumption to improve one’s quality of life. Mindful consumption entails adopting a conscious mindset and moderating one’s behavior to consider the consequences of consumption and ultimately supporting sustainability. Minimalism is a lifestyle and design philosophy focusing on reducing excess and clutter to prioritize what is essential. Frugality is the practice of being economical with resources, particularly money, by prioritizing careful and efficient use of finances. Finally, anti-consumption refers to a resistance to, aversion toward, or even resentment of consumption (see also Boycott and Buycott).

While these practices intersect and may be steps toward VS, this lifestyle is distinguished by its commitment to simplifying life for its intrinsic benefits – such as clarity, purpose, and inner peace – rather than merely reducing possessions, cutting expenses, or opposing consumption. It is a holistic lifestyle aimed at enriching life quality by fostering a connection to one’s values and a balanced, intentional existence.

Application

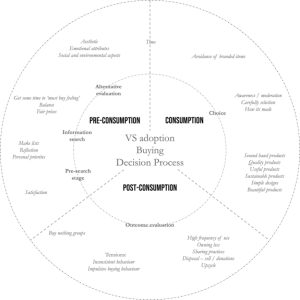

VS manifests in deliberate practices of restricting material consumption and is thus intrinsically linked to consumer behavior. Consequently, we can identify VS-related practices across all stages of consumer behavior (Figure 15.1). In the pre-purchase stage, for example, individuals may engage in a more intentional and thoughtful process of identifying needs and evaluating product options, while carefully choosing the items to buy. During the purchase stage, simplifiers may avoid branded items and instead prefer second-hand products, long-lasting items, and sustainable products. In the post-consumption stage, sharing practices or practices of reusing and recycling may be adopted (see Circular Economy and Society, Sharing Economy, Repair).

Thus, VS can manifest in a wide range of life activities, consumption experiences, and work preferences. In a netnographic study, eight primary life practices in which VS may be enacted were identified: material and digital decluttering, work, routines, hobbies, eating, clothing, gift-giving, and fitness (see Table 15.2 for some examples).

Given the increasing number of consumers adopting VS and its relevance for sustainability, companies need to consider the managerial implications of this lifestyle when designing their business strategies (see The Role of Business). Governments and businesses need additional focus on the well-being benefits of reduced materialism – for citizens and national healthcare budgets – and ensure that marketing and advertising do not seek to obfuscate the benefits of VS and similar practices.

Source: Adapted from Rebouças and Soares (2021)

| Dimensions | Examples of practices |

|---|---|

| Work | Part-time work, Flexible schedule, Early retirement |

| Leisure & routines | Outdoor activities, Hobbies, Crafts, Volunteering, Journaling, Meditation/mindfulness practices |

| Clothing | Capsule/simple wardrobe, Natural materials, Ethical clothing, Rental/second hand/upcycling |

| Gift-giving | Experience gifts, Consumables, Books, Plants, Local stores |

| Material and digital decluttering | Books/ebooks/library card, Organization hacks, KonMari method |

| Eating habits | Simple meals, One meal per day, Eating less meat |

This calls for measures as basic as limiting advertising and marketing, prioritizing basic needs over luxuries, and restricting practices such as planned obsolescence and the rampant introduction of new product models with no significant improvements in functionality (see Ecodesign, Extended Producer Responsibility, Greenwashing). Similarly, characteristics such as durability, reusability, reparability, and multifunctionality need to be reintroduced to help simplify choices.

Further Reading

Aidar, L., & Daniels, P. (2020). A critical review of voluntary simplicity: Definitional inconsistencies, movement identity and direction for future research. The Social Science Journal, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/03623319.2020.1791785.

Devenin, V., & Bianchi, C. (2023). Trajectories towards a voluntary simplicity lifestyle and inner growth. Journal of Consumer Culture, 23(3), 497–516. https://doi.org/14695405221122065.

Elgin, D., & Mitchell, A. (1977). Voluntary simplicity. Planning Review, 5(6), 13–15.

Gregg, R.B. (1936 [2009]). The value of voluntary simplicity. Wallingford, PA: Pendle Hill.

Rebouças, R., & Soares, A.M. (2021). The consumption behaviour of beginner voluntary simplifiers: An exploratory study. Journal for Global Business Advancement, 14(4), 433–452.